<a href="http://www.istockphoto.com/photo/hydrocodone-has-dark-side-as-recreational-drug-gm155132832-18222596?st=_p_hydrocodone">Roel Smart</a>/iStock

Last year, nearly 20,000 Americans died of overdoses involving opioids, a class of drugs including heroin and prescription painkillers like Vicodin, Percocet and fentanyl. A big driver of the crisis: Easy access to the painkillers, which were prescribed to 259 million Americans in 2012—enough for each adult to have a bottle of pills.

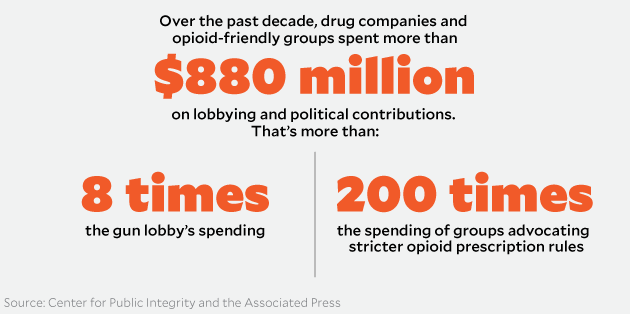

But politicians haven’t done a whole lot to limit accessibility to the drugs. A recent investigation from the AP and the Center for Public Integrity may help explain why: Over the past decade, pharmaceutical companies have spent more than $880 million on lobbying and political contributions at the state and federal level. That’s more than eight times what the gun lobby and more than 200 times what those advocating for stricter prescribing rules spent over the same time period.

“The makers of prescription painkillers have adopted a 50-state strategy that includes hundreds of lobbyists and millions in campaign contributions to help kill or weaken measures aimed at stemming the tide of prescription opioids,” the authors conclude. The investigation looked into contributions from drug companies as well as lobbying groups like the Pain Care Forum (PCF) and the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network (CAN).

PCF was founded by a lobbyist for Purdue Pharma, creator of OxyContin—the same company that paid a $600 million fine in 2007 for misleading the public about the addictive qualities of the drug. CAN is a lobbying branch of the American Cancer Society that is partly funded by drug companies. The group argues that cancer patients should have access to pain medications.

Of the contributions over the past decade, $80 million went to state and federal candidates. But most of the money—$746 million—was spent on lobbying. A few examples of the money in action:

- At least 21 recent state bills with nearly identical language would require insurers to cover abuse-deterrent painkillers, a new class of opioids that are harder to crush or inject. Several sponsors say the language came from pharmaceutical lobbyists. Such legislation is particularly lucrative for pharmaceutical companies because generic versions don’t yet exist. But many have concerns about their efficacy; the Food and Drug Administration notes, “Abuse-deterrent is not the same as abuse-proof,” largely because the drugs don’t “deter one of the most common forms of opioid abuse—swallowing a number of intact tablets or capsules.” The legislation passed in Maine and Massachusetts, failed in New Mexico, and was vetoed by New York and New Jersey governors Cuomo and Christie, respectively.

- When lawmakers in Washington state introduced the nation’s first legislation that would curb prescriptions for high doses of opioids, in 2007, the Pain Care Forum spent $85,000 on a public relations consultant to help persuade state medical officials that the bill would be harmful. Executives from Purdue Pharma chimed in with a letter to one of the state’s medical directors: “While we agree that an opioid should be discontinued if it causes significant adverse effects that are not otherwise manageable, this does not preclude a trial of another opioid,” they wrote. Still, the legislation passed, leading the American Pain Foundation to ask at least one pharmaceutical company for help in order to avoid similar bills.

- In New Mexico, which has the nation’s second-highest opioid overdose rate after West Virginia, lobbyists successfully fought against a 2012 bill that would have limited prescription painkillers for acute pain to 7 days. That year, pharmaceutical companies spent $32,000 on lobbying—more than double the previous year.

- In Tennessee, Pain Care Forum members contributed more than $1.6 milion to the state’s politicians over the past decade, including contributions to state representatives sponsoring opioid-friendly bills that make it easier for doctors to prescribe painkillers for workers compensation patients. When Tennessee lawmaker’s legislation to reduce the number of babies born addicted to opioids failed, he was surprised to learn that one big opponent was ACS-CAN. “We injected ourselves into the debate because we did not want cancer patients to not be able to have access to their medication,” said Theodore Morrison, a CAN lobbyist at the time, to the investigation authors. (Treating cancer patients with opioid painkillers would have remained legal.)

The pharmaceutical companies and lobbying groups claim that Americans should have adequate access to medications to relieve pain, and they stand against abuse of the drugs. Dr. Andrew Kolodny, founder of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, has a different take. “The opioid lobby has been doing everything it can to preserve the status quo of aggressive prescribing,” he told the AP and CPI. “They are reaping enormous profits from aggressive prescribing.”