David Bro/ZUMA Wire

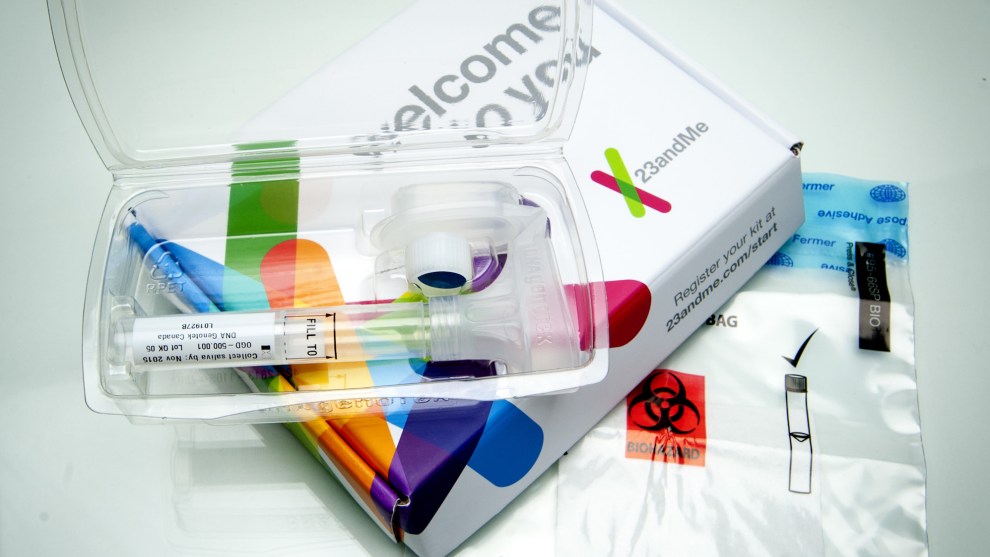

On Wednesday, President Donald Trump announced an end to administration’s policy of separating families at the border. But the administration hasn’t figured out how to reunite the parents and children that have already been split apart. A day after Trump’s announcement, Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Calif.) suggested a novel idea: recruit 23andMe, the DNA-testing company, to help separated families find missing relatives. The company itself quickly volunteered its services for the cause. But legal and genetic experts say that the solution might cause more harm than good.

Speier told Buzzfeed News on Thursday that she spoke with executives at 23andMe, which is headquartered in the congresswoman’s district, about providing testing assistance to reunite families at the border. By Thursday evening, 23andMe CEO Anne Wojcicki said that the company “would welcome any opportunity to help” and was “waiting to see the best way to follow up and make it happen.” (23andMe donated $5,000 to Speier’s 2016 campaign.)

We've heard from many of our customers that they would like to see 23andMe help reunite family members that were tragically separated from each other. Connecting and uniting families is core to the mission of 23andMe. We would welcome any opportunity to help.

— Anne Wojcicki (@annewoj23) June 21, 2018

It’s inspiring to see the massive outreach around helping these families. 23andMe has offered to donate kits and resources to do the genetic testing to help reconnect children with their parents. We are waiting to see the best way to follow up and make it happen.

— Anne Wojcicki (@annewoj23) June 22, 2018

“I implore the President, Attorney General Sessions, and HHS Secretary Azar to accept this generous and altruistic offer, particularly in light of the fact that this administration has provided no evidence of consistent tracking of these children and their parents and nothing in the way of a coherent plan to reunite these families,” Speier wrote in a statement on her Facebook page on Friday. “DNA samples can be taken from all those in custody, with a commitment to respect their privacy, to ensure that these children are not made orphans by the American government.”

According to a spokesperson from Speier’s office, they’ve reached out to Health and Human Services to discuss how to implement such a system.

“The administration would have to agree with it, obviously, and we have not heard from them yet,” Speier’s spokesperson tells Mother Jones. While details of the arrangement would still need to be ironed out, Speier’s office said that she would hope for a system where the database would only exist “temporarily.” Her office cited precedent in a similar system that was employed during Hurricane Katrina to identify victims. DNA testing to confirm family matches between unaccompanied minors and parents was also implemented by the Obama administration through its Central American Minors Program, a program that was discontinued under Trump.

But while tapping a private company like 23andMe might seem like a smart idea to expedite the reunification of families at the border, the solution comes with inherent privacy risks for migrants. Commercial DNA databases are subject to police subpoena, which could expose migrants who have repeatedly been called “criminals” by the Trump administration. The policing potential of commercial databases like 23andMe made news in May when police identified the suspected Golden State Killer after finding a familial match through the site GEDmatch, a commercial database of roughly 1 million profiles.

“It might seem like a silver bullet,” says Natalie Ram, an assistant professor of law at University of Baltimore, “but there are probably less privacy invasive ways that should be explored first.”

Ram cited a number of potential problems that could arise from DNA testing to match families, namely how to guarantee proper consent and prevent misuse of the data after its collection. Ram says that there are precautions that 23andMe could take, such as destroying the data after its used and not registering it to the company’s database.

But how and when that data is deleted could still expose families, says Marcy Darnovsky, executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society, a nonprofit policy group that promotes responsible use of genetic material. She says Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services require labs to hold onto data to later verify their methods. As Bloomberg reporter Kristen Brown recently discovered, even after “deleting” her data, 23andMe would keep her genetic information for “a limited period of time, 10 years pursuant to CLIA regulations.”

Ram suggested that one alternative to using 23andMe would be having the government register DNA to the federal missing person’s database. Legally, this DNA would not be intended for use in criminal investigations, she says. Currently, DNA collection is mandatory in all 50 states for some felony crimes, but crossing the border for the first time is a misdemeanor offense. And in many cases of asylum seeking, it might not be a crime at all. It’s unclear where the current attorney general falls down on this, but in 2008, the Justice Department instructed federal agencies to “collect DNA samples from individuals who are arrested, facing charges, or convicted, and from non-United States persons who are detained under the authority of the United States.”

In addition to the problem that not all family relations are genetic—23andMe’s DNA testing wouldn’t be able to help adoptive parents reunite with their children, for example—Ellen Wright Clayton, a professor of health policy and law at Vanderbilt University, says that there are concerns with how 23andMe would respond to requests from the government to use the genetic data gathered for unrelated purposes.

“[23andMe] actually have a pretty strong policy of protecting their data, but the fact of the matter is that if a government goes to them with a warrant and subpoena there’s not much they can do but say ‘yes,'” says Clayton. “I would think that these people who are obviously a target of the government right now obviously have to be concerned with how 23andMe would protect their data.”

“I would be extremely concerned about this and [the possibility] that law enforcement would be interested in asking for that data,” says Jen King, director of consumer privacy at the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law.

According to a law enforcement guide available on 23andMe’s site, the company “requires valid legal process in order to consider producing information about our users” and “will only review inquiries as defined in 18 USC § 2703(c)(2) related to to a valid trial, grand jury or administrative subpoena, warrant, or order.” A spokesperson for 23andMe told Mother Jones the company had nothing to add to Wojcicki’s tweets at this time.

Clayton says while there is no reason to believe that 23andMe’s interest in providing help isn’t coming from a place of goodwill, if not an attempt at good PR, resorting to genetic testing results in serious longterm consequences. “This is a tool that could potentially be helpful for [families], but in the current political environment it might be too risky to do that,” says Clayton. “This is a real tragic catch-22 from my perspective because we’re hearing that many children of the families have no way of finding their parents.”

Ram and King expressed concern over questions of consent, both because its unclear who is currently the legal guardian of the children and because parents would be signing over their genetic material in a state of distress.

Speiers allegedly isn’t the first government official to suggest DNA matching as a solution. Tony Perkins, Family Research Council President, told the Daily Caller on Wednesday that Attorney General Jeff Sessions was considering the use of DNA testing to verify family claims and that migrants “are parents and not traffickers.” Speier’s office told Mother Jones that the Congresswoman does not want the DNA testing to be handled by the Department of Justice.

To help reconnect parents and children, we intend to offer our genetic testing services through non-profit legal aid organizations representing these families. We are well aware that genetic data contains highly personal information and we want to ensure that it is handled confidentially and with the consent of anyone tested. Providing our testing through legal services ensures attorneys of the families can protect their privacy by only using this data to assist in reunification efforts. It’s incredible to see the community come together to help bring these families back together.