At the end of a long day in January 2011, Brittney Bruster, 28 years old and eight months pregnant, lay down on her sofa to rest. A few minutes later, she was swept by a wave of nausea, followed by a mighty urge to push. She called 911, but “by the time they got there,” she recalls, “I had had her in my sweatpants.” Bruster, who had given birth to four children, was rushed to a hospital in Greenville, South Carolina, with her premature daughter, Tianna, who weighed just five pounds and four ounces.

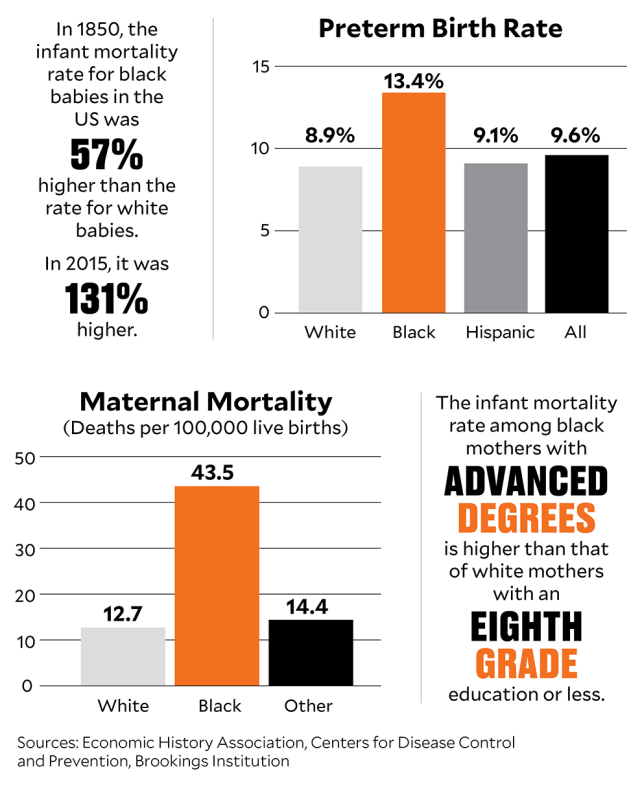

Of all the dangers facing newborn babies, the most dire is coming into the world early. Despite rapid advances in neonatal intensive care technology, nearly 70 percent of newborn deaths in the United States are the result of premature birth. African American women like Bruster have long been at the highest risk for early delivery. Between 2013 and 2015, more than 13 percent of African American babies were preterm, compared with about 9 percent of babies of other races. Black moms are also far more likely to die from birth-related complications. These disparities persist even when you factor in age, income, and the quality of prenatal care. So what’s going on? Recent research has identified one likely culprit: chronic stress related to racism.

A Centering group meets in Greenville, South Carolina.

Melissa Golden / Redux

Scientists have known for decades that chronic stress can activate the cascade of hormones that kick-start labor. Everyone experiences stress, of course, but researchers think certain kinds of stress are more insidious than others. A 1997 study of nearly 60,000 black women found that mothers who said they experienced frequent and severe incidents of racism were at increased risk for preterm birth. Twenty years later, a new study suggested the problem went deeper—even feelings of racial oppression seemed to increase the risk. A team led by Paula Braveman, a family medicine specialist at the University of California-San Francisco, asked more than 10,000 mothers a single question: “How often have you worried that you might be treated or judged unfairly because of your race or ethnic group?” African American women who said they worried “very often” or “somewhat often” were twice as likely as other black women to have had a premature baby. The findings persisted even when adjusted for income, education, age, and medical risk factors. “We were quite floored,” Braveman recalls.

Additional research has supported the hypothesis that racism-related stress causes more black women to have preemies. “It’s just speculation,” Braveman says. “But it’s not crazy speculation.” And the theory’s credibility has been bolstered by a surprisingly simple, cost-effective way of reducing black women’s risk of premature birth.

In the late 1990s, a handful of hospitals started providing pregnant women with prenatal checkups in small groups rather than individually. Women with similar due dates would gather for a few hours each month with a nurse practitioner who would answer questions and lead discussions. Studies found that the women who took part had fewer complications and preterm births than women who saw practitioners on their own. The creators of the program eventually founded a nonprofit called CenteringPregnancy, which has spread the model to 500 sites nationwide.

On a warm day in February, I sat in on a Centering session in a large, cheerfully decorated classroom in Crockett’s clinic. There was a circle of chairs and, across the room, an exam table where a nurse practitioner conducted checkups. The women, who were 34 to 38 weeks pregnant, had been meeting every two weeks for four months, and they shared an easy familiarity, griping about backaches and heartburn. The group included five women of four racial backgrounds, including Bruster, who was expecting again after Tianna’s birth seven years earlier. The model’s founders weren’t focused on racial disparity when they developed it—just reducing pregnancy complications. But about a decade ago, Amy Crockett, an obstetrician in Greenville, wondered whether the strategy might help her pregnant patients, about 40 percent of whom are black. A pilot program, funded by the March of Dimes, proved popular: Patients kept signing up and showing up, saying they cherished the opportunity to befriend other mothers-to-be. But the eye-opener came when Crockett found that her 330 Centering patients were nearly 50 percent less likely to have had preterm babies than the women in individual care. Even more astonishing: Among the program’s participants, the racial disparity in premature births had dwindled. Crockett also noted that the placentas of women who went through her clinic’s Centering program were healthier—and contained fewer chronic stress markers.

Nurse practitioner Deborah Boling summoned Bruster to the exam table and used a fetal monitor to find the baby’s heartbeat—the whoosh-whoosh played over the computer speakers loud enough for everyone to hear. “She sounds marvelous,” Boling said. Bruster beamed, hopped off the table, and returned to the circle, where a lactation consultant led a discussion on breastfeeding. The women asked candid questions: Would breastfeeding make their breasts saggy? (Maybe.) Is it safe to smoke pot while nursing? (Nope.)

Tamera Singleton gets a checkup at her Centering session.

Melissa Golden / Redux

Afterward, they chatted while helping themselves to juice boxes, crackers, and fruit. I asked how they felt about the group. “I wasn’t sure if I wanted to do it,” Bruster said. “But then everyone started bonding with each other.” The others concurred. During an earlier session, Bruster had shared the harrowing tale of Tianna’s premature delivery. “It actually felt good to tell that experience,” she said.

Crockett points out that most of her pregnant patients still opt for individual care in part because Centering is a bigger time commitment. And there are institutional obstacles, says Sarah Covington-Kolb, a public health researcher who helps run the clinic’s program. Centering costs the clinic up to three times more than traditional care. But Crockett calculates that when you figure in the astronomical price of keeping a preemie in intensive care, Centering likely saves money in the long run. Using this argument, in 2013 she convinced South Carolina’s Medicaid office to fund Centering programs statewide, a move that has already saved the state about $4.7 million. Early results from a state-funded study show that women who took part in Centering had a preterm birth rate of 7.6 percent overall—well below the national average. For black women who tried Centering, the preterm birth rate was 9.5 percent. “We’re doing something a little bit better,” says Covington-Kolb. “And it’s helping.”

Researchers and doctors acknowledge it will take more than Centering groups to permanently close the racial gap in pregnancy and birth outcomes. Yet the growing evidence of their effectiveness is promising, and so are the individual success stories. On April 2, Bruster gave birth to her daughter Isley-Rai—full term, eight and a half pounds, and healthy.