Brian Cahn/Zumapress

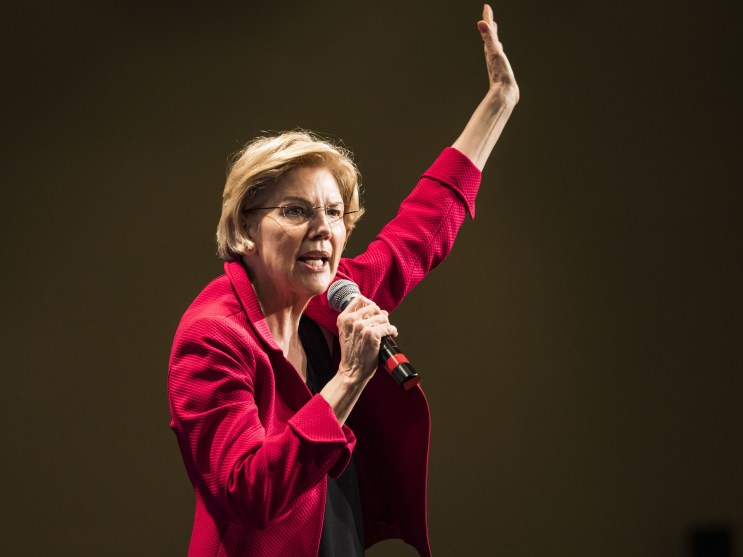

Elizabeth Warren has made fighting Wall Street central to her political career, and she’s prepared to double down if elected president.

That’s the overall message of Warren’s newest detailed plan, unveiled on Thursday, to reel in financial industry excess, from high-risk investing to executive compensation to the private equity industry. The proposal is the second plank in her “economic patriotism” agenda, which Warren’s campaign first announced last month when publishing plans to overhaul the country’s trade and manufacturing policy.

“Wall Street is looting the economy and Washington is helping them do it,” Warren writes in a Medium post outlining the proposal. “To raise wages, help small businesses, and spur economic growth, we need to shut down the Wall Street giveaways and rein in the financial industry so it stops sucking money out of the rest of the economy.”

Warren’s plan is expansive, with ideas touching virtually every corner of the financial sector. One of the proposal’s most robust features is a new regulatory infrastructure for the private equity industry, which buys and restructures companies and, unlike larger financial firms and banks, is subject to weak oversight.

Warren notes that in the process of restructuring companies, private equity firms often make decisions that prioritize their own profits over the health of the company they’ve just purchased, by selling off assets, firing workers, slashing costs, charging high management fees, or saddling the companies with new debt. If the acquired businesses eventually fail, the private equity firm still keeps their profits. Warren calls this “legalized looting.”

She proposes a series of legal changes to shift private equity’s incentives, by enacting rules so that private equity firms can only profit when the companies they control do well. Warren would also require private equity to fulfill pension obligations at the purchased companies, rein in private equity’s high management fees, and discourage institutions from lending to companies owned by private-equity firms that already hold massive debt.

Warren also suggests changing the tax code so that the private equity industry pays more taxes both on the debt it buys, and on the profits its executives reap. Thanks to the carried-interest loophole, those profits are currently taxed as capital gains, rather than earned income, giving private equity bosses an enormous tax savings. In doing so Warren is proposing to make good on a promise once made by President Donald Trump, who campaigned on closing the carried-interest loophole but has made no moves to do so.

Beyond private equity, Warren’s plan includes steps to tighten banking regulation. She proposes breaking up big banks, by separating the commercial banking functions that manage regular accounts from bank arms that oversee high-risk investments. Commercial banks receive government-subsidized deposit insurance in order to affordably serve people. Warren argues that bank’s investment arms should not be benefiting from this taxpayer-funded aid.

“If banks want access to taxpayer-subsidized insurance, they should be forced to limit their activities to boring banking,” she writes. This banking proposal amounts to a modernized version of the Glass-Steagall Act, a law that, until its 1999 repeal, required separation between commercial and investment banking. Some experts believe the repeal of Glass-Steagall helped cause the 2008 financial crisis, by encouraging banks, assured of a taxpayer-funded safety net, to make riskier investments.

Other proposals released today include a system of low-cost postal banking, aimed at improving access to bank accounts for the approximately 25 percent of U.S. families who either don’t have accounts, or do but still rely on services outside of traditional banking, like payday loans.

Warren also proposes imposing new rules on bankers’ compensation to discourage them from making highly-risky investments. She also pledges to appoint regulators who will undo the Trump administration’s easing of key safety measures imposed on banks after the financial crisis.

“Trump-appointed regulators have chipped away at the rules for big banks, asserting that they limit the potential for economic growth and hoping that nobody understands these technical rules well enough to push back,” she writes. “Well I do understand them. I know that these rules not only make the financial system safer, but also channel big bank activity into more economically productive ends.”