“No person should lose the right to liberty simply because [they] can’t afford to post bail," the California Supreme Court ruled today.Shutterstock

In a ruling likely to transform the bail system of the nation’s largest state, the California Supreme Court held today that courts must weigh a defendant’s finances in setting bail. “Conditioning freedom solely on whether an arrestee can afford bail,” Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar wrote in the court’s unanimous decision, “is unconstitutional.”

California has the second-highest pretrial detention rate in the country, according to a report by the Vera Institute of Justice. Roughly 40,000 of the people in California’s jails—more than 50 percent of its total jail population—are incarcerated while awaiting trial. About half of them are there because they simply can’t afford bond. Nationwide, almost three-fourths of the US jail population had not been convicted of any crime, the Prison Policy Institute found in 2020. The pandemic has further prolonged pretrial custody: according to a University of California, Los Angeles, study, 41 percent of Los Angeles County defendants spent six or more months in jail while awaiting trial—up from 35 percent before the pandemic. Of the study’s 400 participants, 94 percent reported inability to pay bail.

Today’s ruling is four years in the making: In 2018, a California appeals court issued a landmark ruling in the same case, In re Kenneth Humphrey, requiring judges to take into consideration a person’s ability to pay in setting bail rather than relying strictly on bail schedules.

In May 2017, Humphrey, a 63-year-old Black man, was charged with theft: stealing $5 and a bottle of cologne from his neighbor at a San Francisco single-room-occupancy hotel in 2017. His bail was set at $600,000; Humphrey did not have $600,000. When he agreed to undergo a drug rehabilitation course, it was reduced to $350,000. He didn’t have $350,000 either.

When Humphrey fought to be released on his own recognizance without money bail, he told the judge about his age, the fact that he was unemployed, and his lack of financial resources. The trial courts denied his request. After much petitioning, Humphrey was released without having to pay bail—he instead had to wear an electronic ankle monitor and participate in a substance abuse program. (One of his lawyers was then-deputy public defender Chesa Boudin, now San Francisco’s district attorney.)

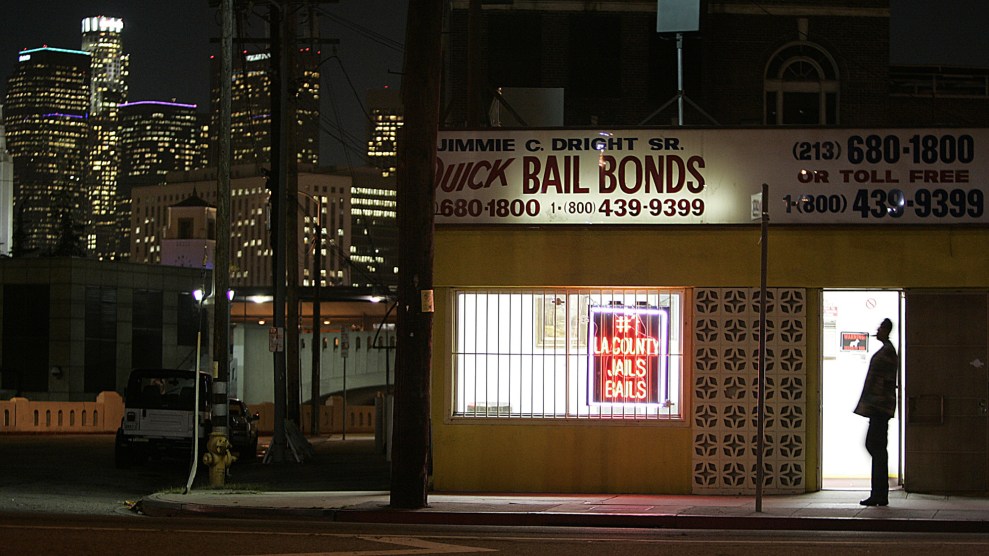

The fight didn’t stop after Humphrey was released. In California’s legislature, Senate Bill 10, which would have replaced the state’s money-based pretrial detention with a system of risk assessments, was signed into law in 2018 by then-Gov. Jerry Brown. But Californians voted down a 2020 ballot initiative to get rid of cash bail, preventing the 2018 law from going into effect. Some progressive voters objected to the bias associated with algorithmic, risk-based assessments that might replace cash bail, while conservatives objected on law-and-order grounds—and bail-bonds firms, which feared their doors would be shuttered, objected most loudly of all.

The Supreme Court ruling follows on the heels of a groundswell of support for criminal justice reforms across the state. In San Francisco and Los Angeles, respectively, district attorneys Boudin and George Gascon have barred their deputy prosecutors from seeking cash bail for misdemeanor and non-violent offenses.

Humphrey’s case “challenges this system with a claim as simple as it is urgent,” Justice Cuellar wrote in the court’s opinion. “No person should lose the right to liberty simply because that person can’t afford to post bail.”