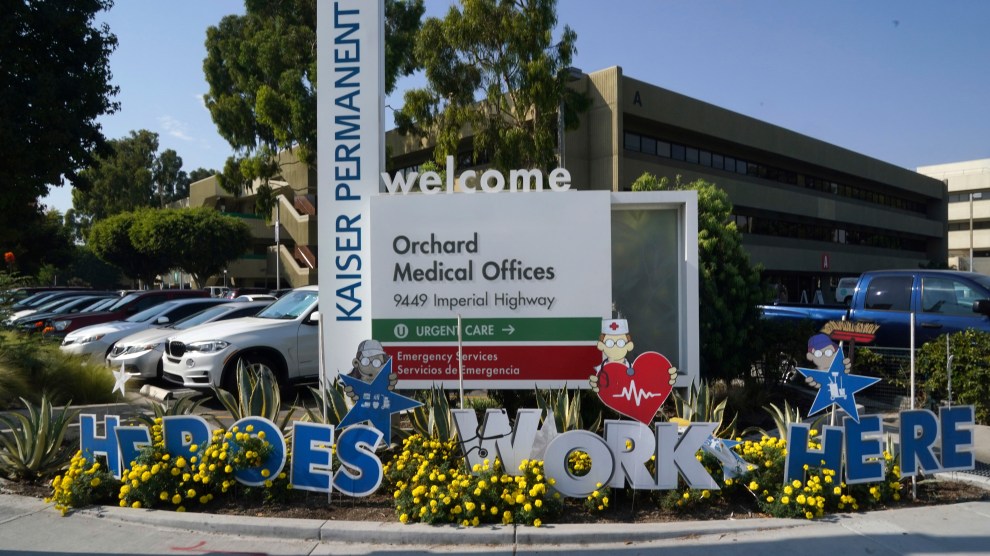

(Kirby Lee/AP)

Kaiser Permanente reached a tentative agreement with its workers’ unions Saturday, handing its workers a big victory and averting what would have been a historic strike by two days.

More than 30,000 employees had vowed to strike on Monday if the company did not reach an agreement with the unions. As my colleague Noah Lanard wrote last month, the health care workers threatening to walk off the job were particularly upset over the so-called two-tiered pay structure that Kaiser had proposed:

Workers’ biggest problem with the wage proposal is that it would cut starting pay for new hires by between 26 percent and 39 percent beginning in 2023. They believe it would deepen an existing staffing crisis at Kaiser’s facilities and put patients at risk by making the nonprofit unable to recruit and retain talented workers. There are also fears that it would lead to resentment among those paid less for the same work, or cause Kaiser to replace the more expensive workers covered by the old contract with new hires. Kaiser’s push for two-tier pay resembles similar proposals from Kellogg and John Deere that have already led to strikes this fall.

Essentially, workers feared that Kaiser was trying to create a caste system within their ranks, paying workers who do the same jobs, even side by side, different salaries and benefits. These kinds of moves can splinter workers into different groups of have-somes and have-lesses, making it harder for them to organize in the future. In the end, Kaiser dropped its push for the two-tiered pay system.

The health care giant had defended the proposed cuts as necessary to stay competitive, but the numbers tell a different story. In 2019, Kaiser gave its outgoing CEO Bernard Tyson a $35 million pay and retirement package. During the pandemic, it made $10 billion. And it made that money while its workers were ground down by the grueling conditions of laboring through a global pandemic.

In his October story, Noah detailed the intense situations that some of these workers have had to endure while their company’s bottom line has thrived. Take the case of Hollie Sili, an emergency room technician:

These days, Sili usually works a 12-hour shift from noon to midnight. But due to staffing shortages, she often ends up staying until 4 a.m. before returning for another shift eight hours later. Last year, she had a stroke, which she attributes to the physical and mental stress she’s experienced at work.

Or Daniel Stretch, a hospital engineer:

Stretch, the hospital engineer, estimates that his workload and stress levels have doubled during the pandemic, while pay has remained the same. He and roughly two dozen other engineers are responsible for keeping air conditioners, humidifiers, sterilization machines, cooking equipment, TVs, nurse call buttons, and much more running at their Southern California facility. In pandemic times, they scrambled to push air circulation systems beyond their normal limits to protect patients from COVID-19.

Or Katie Johnson, an oncology infusion nurse at a Kaiser clinic in Longview:

Johnson, an oncology infusion nurse at a Kaiser clinic in Longview, Washington, doesn’t see how new hires would be able to pay off their nursing school debts and maintain a decent standard of living after a 39 percent cut to starting salaries. Even at today’s higher rates, she ended up moving to Longview after being priced out of the housing market 50 miles south in Hillsboro, Oregon. She says Kaiser has always operated on a lean staffing model, but that things have only gotten worse as colleagues left the field during the pandemic. “If we can’t attract the talent now,” she asks, “how are we going to attract talent at a lower rate?”

Had the strike happened, it would have been one of the largest in American health care history, and it would’ve come on the heels of an uptick of labor activism that observers have dubbed Striketober.