This story is a collaboration between The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Mother Jones, and Enlace Latino NC.

When the tobacco giant Reynolds American cut a check for Brent Jackson’s political campaign in November 2019, it was well aware of the accusations against the Republican North Carolina state senator.

Jackson—dubbed “the only mega-farmer” in the North Carolina senate—had been accused by several migrant workers of either failing to pay their wages or blacklisting them for joining a union, according to court documents. In 2019, he was still in the midst of one of those court cases. But the cigarette maker’s relationship with Jackson goes beyond politics. They also do business together.

At North Carolina’s capitol in Raleigh, Jackson has become a powerful force in the state’s corridors of power. Head south, though, to his home in Sampson County, and you’ll find his farm: thousands of acres of land where scores of seasonal migrant workers toil in the sun to pick watermelons, cantaloupes, sweet potatoes—and tobacco.

An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Mother Jones and Enlace Latino NC can reveal how Reynolds American has pumped a significant amount of money into Jackson’s campaign. In fact, few lawmakers in the Tar Heel state have received more money from the company than Jackson, who has in turn used his platform to promote bills that prevent his workers speaking out against abuse.

Interviews with migrant workers employed on his farm reveal why they felt compelled to speak out. The union took its concerns about Jackson’s farm directly to Reynolds American, first in 2015 and again in 2019. But, despite senior executives’ claims that the company supports the freedom of farm workers in its supply chain to unionize, Reynolds continued to buy tobacco from Jackson’s farm and to help fund his political career.

“It’s hypocritical,” said MaryBe McMillan, president of the North Carolina State AFL-CIO, an association of unions. “Reynolds has been union-busting for a long time, so I really don’t necessarily believe that they support freedom of association.”

North Carolina is the worst state to work in America according to Oxfam, and has some of the lowest rates of unionization in the country. In some states, one in four workers are part of a union. In North Carolina, it’s one in 30, and farm workers are often not afforded the few protections granted in other industries. Jackson wants to keep it that way: in recent years he has spearheaded efforts to even further hinder the power of his workers to organize.

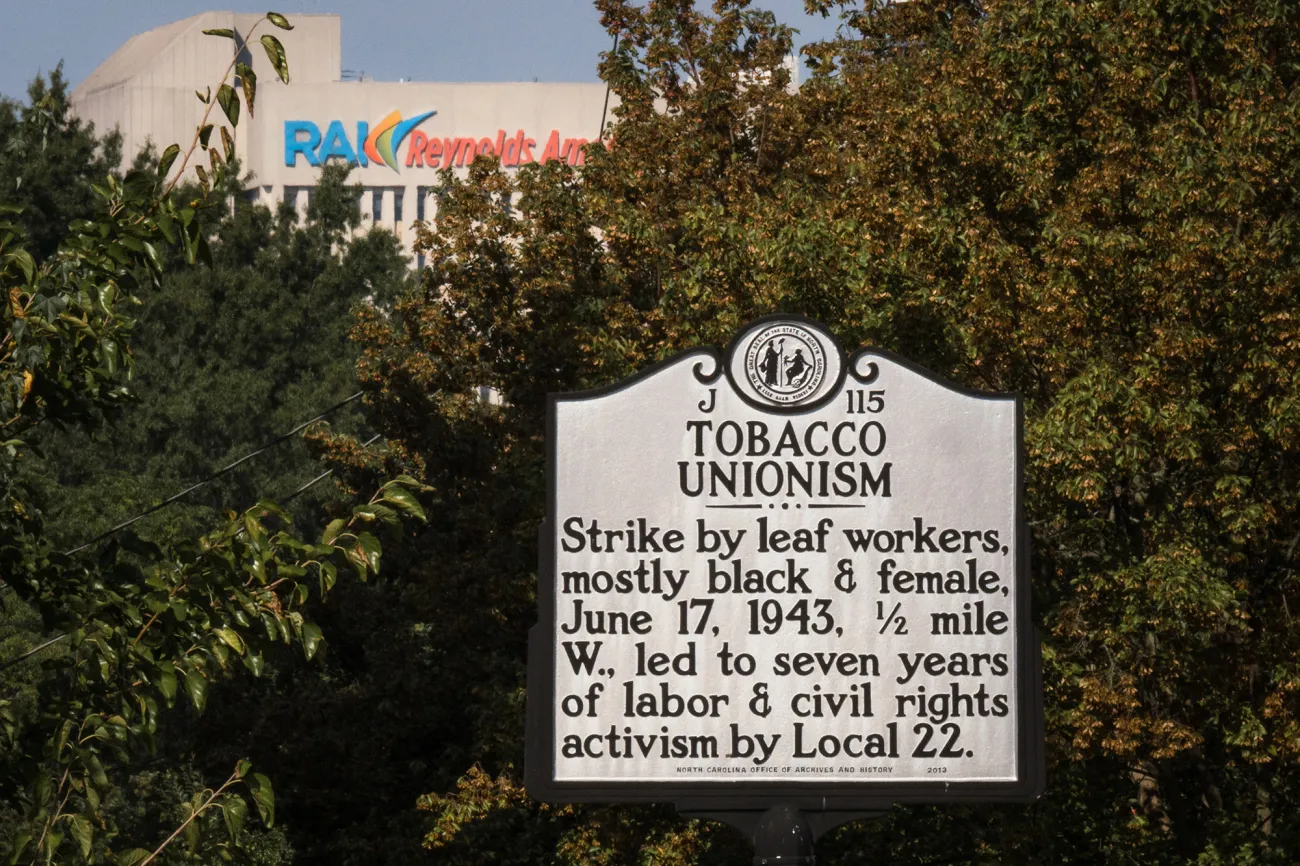

A historical marker about the 1943 strike by tobacco workers sits on the outskirts of downtown Winston Salem, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

In Reynolds American, Jackson has not only found a buyer for his crop but also a generous source of funds for his political endeavors—which include weakening the union that has helped his own employees take him to court.

In 1980, North Carolina’s governor James Hunt said: “In this state, tobacco is still king. And we intend to keep it king.” More than four decades later, the Bureau’s analysis of campaign finance data, combined with depositions and email records contained in court filings, reveals the enduring influence of Big Tobacco on North Carolina politics.

And while Reynolds claims to support freedom of association within its global supply chain, its political donations tell a different story altogether.

Deep roots

Under the shade of a giant oak tree, Carlos sits on a folding chair and takes a deep breath. (The names of workers have been changed to protect their identity.) It’s a Sunday, his day off from working the fields—tomatoes and tobacco currently—in the North Carolina Piedmont region. It’s the day when he rinses off his mud-caked work boots and sets them out in the sun to dry, his tired feet in socks and slides.

Tobacco is a labor-intensive crop. It begins life in a greenhouse before being transplanted into the soil. It grows to a few feet tall and you often start by only picking the leaves at the base of the stem, which has to be done by hand. The early-morning dew makes it give off a greasy chemical smell and the tar slowly turns your gloves black. The nicotine in tobacco keeps smokers hooked, but for workers in the fields who are exposed to nicotine day in, day out, it can cause “green tobacco sickness”—a condition that leads to headaches, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. A day off is a welcome respite.

Carlos rests inside the bedroom he shares with three of workers.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Carlos sits under a tree near a clothes line where he and other workers hang their clothes to dry.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Behind Carlos, a few men hang laundry on a clothesline. He squints to see which of his fellow workers have come out of the old, large house they all share. It’s comfortable enough, especially compared to the accommodation he remembers at Jackson’s farm.

“Some of us get along, but not all of us,” he says in Spanish. He jokes that living among 16 farm workers in one house for six months out of the year is like being on a reality show without the cameras. But the camaraderie that does develop is what gets them through the season.

Carlos says that despite the physically grueling work—repeating the same action hundreds of times a day—his current setup is far better than when he first came to the US seven years ago, as a seasonal agricultural worker on what is known as a H-2A visa. That first year, Carlos toiled in fields about 100 miles southeast for Brent Jackson and his son Rodney.

“We called it the chicken coop,” Carlos says of the housing provided to him and dozens of other workers on the Jackson farm. “It was just wooden walls and a tin roof… it would rain and all the water would leak in.”

Carlos first arrived on Jackson’s farm in Autryville in the summer of 2015. Immediately, he noticed an “incompetence” with the people in charge. He worked from 7am to 8pm and says he rarely saw the Jacksons.

Brent Jackson, who did not respond to the Bureau’s repeated requests for comment, is hailed as one of the success stories of the North Carolina agriculture industry. The son of a secretary and a barber, he grew up on a small plot of land off a dirt road in the heart of tobacco country, surrounded by the industry that formed the backbone of North Carolina. He got his first taste of tobacco-picking on a nearby farm as a child and never looked back.

“The bug bit me. There was something about working with the soil and just watching things grow and nourishing them,” said Jackson during a recent interview on a North Carolina podcast called Do Politics Better, his words spilling out in a slow Southern drawl.

Over the years, he and his wife Debbie, with the help of Rodney, have grown a small slice of his native Sampson County into a 6,000-acre farm. They now grow a whole host of fresh produce and row crops, such as cotton, peanuts and tobacco, but are best known for their watermelons and cantaloupes, Jackson says. (One of the company’s logos is a raccoon eating a watermelon, invoking the racist caricatures that were popularized during the Jim Crow era in the Southern US.)

A Jackson Farming Company sign sits on the edge of the road near the farm in Sampson County, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

By 2010, in his words, he could “no longer stand back and watch agriculture, our state’s number-one industry, take a back seat in the policies being implemented in Raleigh.” That was the year he was elected a state senator, and he has since emerged as a driving force behind agriculture policy in North Carolina. In 2016, he was one of 64 people appointed to the agricultural advisory committee of then presidential candidate Donald Trump. He told the Do Politics Better podcast that his “lifelong goal” is to become the state’s commissioner of agriculture.

Jackson’s business and public lives appear to have always been inextricably linked. He part-owns a gun shop and is a staunch defender of the Second Amendment, earning himself an endorsement from the National Rifle Association. He has advocated for expanding the hemp industry in North Carolina while renting some of his property to a hemp company. He was behind a scheme that gives grants to farms for improving natural gas infrastructure and later applied for a $925,000 grant from that very scheme (he did not receive any funds).

A few months ago, Jackson was accused of self-dealing. He had bought two warehouses in a nearby town and, after being told that the buildings would need to meet fire safety standards, he authored a bill that expanded exemptions from fire inspections. “He chose to write a bill that would exempt his personal building from compliance,” the North Carolina Fire Marshals’ Association wrote in a letter to the state’s governor in July, according to local TV news station WRAL.

He has also thrown his weight behind policies that critics say have attempted to silence farm workers like Carlos, who have spoken out against mistreatment by North Carolina farmers.

Tobacco-picking is is often done by migrant Latino workers, both H-2A and undocumented. They can face abuse and exploitation from when they are recruited in Mexico, before they even set foot on US soil. But they are essential to the economic stability of North Carolina, providing a steady supply of labour for agricultural jobs that can’t be filled by Americans.

Reynolds American, which is part of the London-based British American Tobacco, does not directly own any farms nor employ any farm workers. Instead, it buys tobacco from farmers like Jackson, independent growers who often use seasonal workers on the H-2A program.

“The tobacco companies essentially looked at it like, ‘These are just suppliers and we have no responsibility for what goes on on the farms,’” said Justin Flores, a North Carolina-based organizer who worked closely with workers on Jackson’s farm as part of his former job with the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), a workers’ union.

When approached by the Bureau, Reynolds pointed to its commitment to ethical farming practice and said it promotes “a robust culture of compliance to ensure all farmers with whom we contract meet or exceed all US laws regarding farm worker employment.”

Carlos stands for a portrait on a tobacco farm in North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Like many who come to North Carolina on the H-2A program, Carlos typically starts by farming vegetables and tobacco before moving west later in the year to harvest Christmas trees. When he returns to Mexico, he works in corn fields but says he only makes 800 to 900 pesos a week, the equivalent of less than $45. In North Carolina, he can earn that in a few hours. “I come [to the US] for my family, for my children. I want to give them a better life,” says the father of four. “I want give them a better life.”

But he says the place he was given to live during the season he spent on Jackson’s farm were “uninhabitable.” And he wasn’t the first to question the treatment of migrant workers there.

Legal struggles

In 1998, long before Carlos arrived on the farm, Carmen Fuentes left his home in a small town in rural eastern Mexico to travel to North Carolina on the H-2A program. His colleagues said he was the best worker at Jackson’s farm that summer.

One hot and humid day, while out picking tomatoes, Fuentes began to feel dizzy. After finding some shade where he could sit and take a break, he was eventually carried back to the camp where he and the other farm workers were living. His colleagues laid him outside on a sheet and left him alone. Jackson’s wife Debbie, who was supervising the farm workers that day, “failed to administer any type of first aid,” according to an official report obtained by the Bureau through a public records request.

Fuentes had suffered severe heatstroke and was only semi-conscious by the time the emergency services arrived. At no point did staff place Fuentes in the nearby produce cooler or air-conditioned office, a decision described as “inexplicable” by an industrial commissioner ruling on the incident. Farm staff were not properly trained to spot the signs of heatstroke despite having been warned about the risks just a few months prior.

His body temperature, taken at the hospital that evening, was more than 42°C (108°F), the highest the thermometer could read. He fell into a coma and doctors feared he might die.

Fuentes survived, but he is not expected to ever recover. For the 24 years since, his sister has been providing him with round-the-clock medical care back in Mexico.

A bus that carries farm workers sits near the entrance of Jackson Farming Company in Autryville, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

After the incident, Jackson Farming Company was fined $2,500 by the North Carolina Department of Labor, the records released to the Bureau reveal. Jackson challenged the penalty but did not succeed.

Health and safety officials visited the farm again four years after the incident. They found that his workers had no toilet facilities in the field and their housing was not up to standard. One trailer had 15 farm workers living in it with only one stove and two working oven burners, according to their report. Six of the bedrooms on the camp were smaller than the minimum standard. One room that contained two beds was only slightly larger than a typical one-person jail cell.

Jackson Farming Company was fined again, this time almost $3,000—a sum that was reduced to less than $500 when it showed it had fixed the problems highlighted by the inspection.

Throughout this time, the farm was part of the North Carolina Growers Association, a group of businesses in the area that pool resources and share the administrative burden involved when hiring H-2A workers. The association is one of the biggest employers of these workers in the US, bringing more than 10,000 to the state every year. In 2004, FLOC negotiated a collective bargaining agreement with the association. It means that, unlike a lot of H-2A workers around the country, those working on its member farms are represented by a union.

In 2014, H-2A workers at Jackson’s farm used the agreement to file a grievance alleging they had been underpaid—and were given what they were owed in back wages. This triggered a tussle between FLOC and Jackson that continues to this day.

By the time Carlos arrived the following year, Jackson’s farm had left the Growers Association. Problems continued but the complaints were quieter now. According to Justin Flores, who was working for FLOC at the time, Jackson’s workers were wary of rocking the boat. Flores said Carlos and his colleagues had been told by the farm that “there’s no more union” and “unions cause trouble”.

Flores began checking in on the workers to see how they were being treated. One had been fired after he complained that his employer tried to take money out of his paycheck to cover repairs to a broken gas pump. He was given 30 minutes to pack up his stuff and get off the property or the police would be called, he later alleged in court. With few other options, he asked a local business owner to pick him up and paid for his own travel back to Mexico, costs that should have been covered by Jackson under the rules of the H-2A program.

It was through the union that Carlos and his fellow workers learned that what was happening to them was wage theft.

“The problem was that when they moved us from one field to another, they would sign us out with our punch cards and not count it as work,” Carlos said, adding that he would lose 30 minutes to an hour every day. “It was about three hours a week.”

He said that workers who were found to have been talking to FLOC were not rehired the following year, and needed the union to find alternative work.

Seven of the workers eventually went to court and, in 2017, won several thousand dollars in backpay. “It was the first time that I demanded something, our rights as workers,” Carlos said. “I felt good because it was something that we had already earned—because it was our job.”

“Their goal wasn’t really about money,” said Flores, the union organizer who worked with Carlos. “They were trying to get better job conditions, better treatment, and the money was the only leverage they had.”

In 2017, two years after Carlos left Jackson’s farm, Roberto arrived. Under the heat of the midsummer sun, the workers toiled for hours on end, sometimes seven days a week. Roberto found life there similar to how Carlos did. The farm’s staff were rude. One even called them “slaves,” Roberto told the Bureau. “Sometimes they wouldn’t even let us drink water,” he said.

He said that he often wouldn’t finish until the early hours of the morning. Workers were pushed to do as much as they could in as little time as possible, he recalls, and their employer would decide when they started and finished, often with little notice.

When Roberto decided to join the union and raise concerns about how workers were being treated, it is perhaps no surprise that he was met with strong resistance. Brent Jackson’s son Rodney refused to meet with him, six other employees and two FLOC representatives. Farm staff threatened to call the police if the FLOC representatives didn’t leave the farm. The union was forced to explain to law enforcement that they hadn’t trespassed and had been invited on to the farm by the workers, who were residents.

Livestock graze on farmland in Sampson County, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

The sun rises over field in Sampson County, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Roberto was willing and able to return to Jackson’s farm in 2018, but he and the others who complained during the 2017 season had been blacklisted, court documents allege. There was no job offer from Jackson’s farm again in 2019. That’s when Roberto and his colleagues decided to take Jackson to court—with the help of FLOC and its lawyer—claiming they had been retaliated against for joining a union. Later that year Jackson agreed to a settlement, the terms of which were not disclosed.

Ever since Jackson first ran for state senator in 2010—and throughout the grievance raised by employees in 2014 and both Carlos’s and Roberto’s court cases—his political ambitions have been continually furthered by tens of thousands of dollars from Reynolds American.

In fact, almost every year since 2010, Reynolds American has given money to Jackson—a total of $17,500 from its political action committee. Only two North Carolina lawmakers have received more from the committee in that time. And Reynolds American has given a similar sum to the North Carolina Republican Senate Caucus, which Jackson is a part of and receives money from.

Reynolds is also one of seven “cornerstone members” of the business lobbying group NC Chamber. Over the last decade it has given more than $200,000 to the group, and Jackson has received $14,500 in NC Chamber funds.

A corporate document lays out how Reynolds American decides which political candidates to donate to: “All proposed corporate contributions go through a review process to … determine that they are in the best interests of the RAI [Reynolds American Inc.] companies.” Despite the company’s commitment to ridding its supply chain of exploitation and endorsing farm workers’ freedom to organize, it has continued to donate to Jackson. Even during his first election campaign in 2010, he was being asked questions about his past conduct and what had happened to Fuentes during the summer of 1998.

The Camel City

“The indelible imprint of tobacco is all over North Carolina,” the Raleigh News & Observer wrote recently. Nowhere is that imprint more evident than in Winston-Salem, a small city in the north of the state.

There, the Reynolds family lends its name to a school, a university campus, a boutique shopping district, a park, a museum, an airport and numerous roads. Looming over the city are a pair of 130-foot smokestack towers bearing the letters RJR, the initials of the man who changed the face of Winston-Salem forever.

A statue of R.J. Reynolds on a horse stands near the city hall in downtown Winston Salem, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

The son of a Virginian slave owner, Richard Joshua Reynolds set off south in 1875 in search of a city to start his tobacco company. For much of the industry’s history in North Carolina, tobacco was harvested by slaves and later poor families, many of them Black and stuck in exploitative share-cropping deals that perpetually indebted them to wealthy white landowners. This system created some of America’s richest families and two of the most prominent were in North Carolina—the Dukes in Durham and the Reynoldses in Winston-Salem.

By the time he died in 1918, his company owned more than 100 buildings in the city and on the day of his funeral, his adopted home mourned the loss of its pseudo-statesman. Local businesses shuttered their doors as thousands of people lined the city streets to pay their respects.

After his death, the RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company continued to dominate North Carolina life. The company erected one of the largest buildings in the southeast at the time, a scaled-down precursor to the Empire State Building, on East 4th Street. The building’s lobby shone with marble and burnished brass.

For generations, the tobacco industry has occupied a central position not only in the economics of the American South but also the politics of the nation at large. Until 2004 the government had been propping up tobacco farmers since the 1930s. And tobacco lobbyists helped the industry push back against stricter regulations, higher taxes and even claims that cigarettes were harmful. When the industry was facing major curbs to its advertising in 1996, Republican presidential hopeful Bob Dole said he didn’t think tobacco was addictive for everyone. Dole’s campaign had received hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations from tobacco companies—which were “the giants of American politics,” according to President Clinton’s special adviser.

Although the vestiges of the tobacco industry’s dominance are still present, times have changed. Smoking rates have declined steeply. The words “RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company” may remain etched above the door of the building on East 4th Street but today it’s the smell of roasted garlic from a French brasserie that greets visitors to what is now a four-star hotel: the company headquarters have moved next door, into a more austere concrete building. And the iconic Reynolds smokestacks no longer belong to a coal-fired power plant but to a sprawling office, entertainment and retail space overlooking Winston-Salem’s “innovation quarter.”

The Reynolds American corporate office can be seen through the two smoke stacks with “R.J.R. Tobacco” written on them in downtown Winston Salem, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

But while its presence may seem to have faded, Reynolds is still here, at the heart of Winston-Salem. And its influence still pervades the city.

Through its foundation, Reynolds American has continued the legacy left by its founder. It donated more than $5 million to charity in 2019 (the most recent data available), most of it to organizations in North Carolina, including universities, schools, medical centers and animal shelters.

A number of other local foundations can be traced back to Reynolds money. One has recently funded a new playground at an elementary school in Winston-Salem. Another, named after one of RJ Reynolds’ sons, has supported groups helping immigrant farm workers and the injustices they face.

The company is also still a major backstage player in political contests, having given $563,000 to North Carolina state candidates since 2010. More than $525,000 of that went to Republican candidates, according to the Bureau’s analysis. These sums are in addition to the hundreds of thousands Reynolds gives to Washington DC groups that influence state elections.

It has also retained the services of well-connected North Carolina lobbyists. Among its ranks are the former Mayor of Raleigh and former chair of the state Republican Party, Tom Fetzer, and a former Democratic state house representative, Edward Hanes. During his stint in office, Hanes received more money from Reynolds American than any other North Carolina Democrat at the time.

A pawn shop named after R.J. Reynolds cigarette brand “Camel” can be seen downtown Winston Salem, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

In the heart of downtown Winston-Salem, outside the city hall, stands a bronze statue of RJ Reynolds sitting atop a horse, the plaque below describing him as a “successful businessman and public benefactor.” There is no better reminder that in North Carolina politics, the specter of the tobacco industry is never too far away.

Rewriting the rules

On April 29 2016, Brent Jackson wrote an email to a contact at the North Carolina Farm Bureau, which lobbies on behalf of farmers. He attached a letter to the email and typed the subject line: “Blackmail”.

The attached letter was from a lawyer representing Carlos and the other former farm workers who had worked on Jackson’s farm the previous year. The lawyer wanted to settle the claims out of court, but only if Jackson would accede to a collective bargaining agreement for workers on his farm.

A few months later, Jackson sent another email to the lobbyist. This time, he forwarded a message from his own lawyer about a draft amendment to a bill. The bill would outlaw people asking for collective bargaining agreements when settling legal disputes—exactly what the farm workers were doing.

“If [the farm workers] insist on including union recognition as part of the settlement … that could be a problem for them if this revision becomes law,” Jackson’s lawyer wrote. “It could potentially be helpful to us.”

A photo of Brent Jackson and his fellow colleagues in the state senate hangs near the door of the senate floor.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Jackson and the NC Farm Bureau worked to ensure the amendment was included in the 2017 Farm Act, a bill co-sponsored by Jackson. Last year, a federal court judged this section of the act to be unconstitutional. FLOC is still fighting a part of the law that prevents it from taking union dues directly from farm worker paychecks, a right afforded to all other private sector workers in North Carolina.

In fact, the day before the governor signed the act into law, the case against Jackson was settled (he did not agree to a collective bargaining agreement). But these emails—released recently as part of a tranche of documents included in a court case brought by FLOC against the act—reveal the Farm Bureau’s access to politicians in North Carolina and the hidden influence of Reynolds American in the corridors of power.

The NC Farm Bureau has emerged as a powerful anti-union voice in the state. Farm Bureau employee Michael Sherman could not have made the group’s position clearer: “Our members have adopted a policy that we are opposed to the unionization of farm workers,” he said during a deposition.

The group has “frequent” conversations with Reynolds American, another employee said. Last year, the company gave $25,000 to Keep Ag Growing, an organization run by the Farm Bureau that has campaigned for Republican candidates in state elections.

One of those conversations between Reynolds American and the NC Farm Bureau was about how the union was seeking an agreement with the cigarette maker that would mean farmers with unionized workers would get a higher price for their tobacco. Afterwards, the NC Farm Bureau drafted language for a bill that outlawed such agreements and was passed in 2013. FLOC’s former organizer Flores told the Bureau that Reynolds American has since “cited that law publicly as a reason why they can’t negotiate an agreement with us.”

Sherman also detailed the remarkable access the organization has enjoyed to state politics, drafting bills and strategizing with a select group of Republican lawmakers, including Jackson and another tobacco farmer-turned-politician, David Lewis, on how to get them passed. The NC Farm Bureau did not respond to questions about its lobbying and its relationship with Reynolds American.

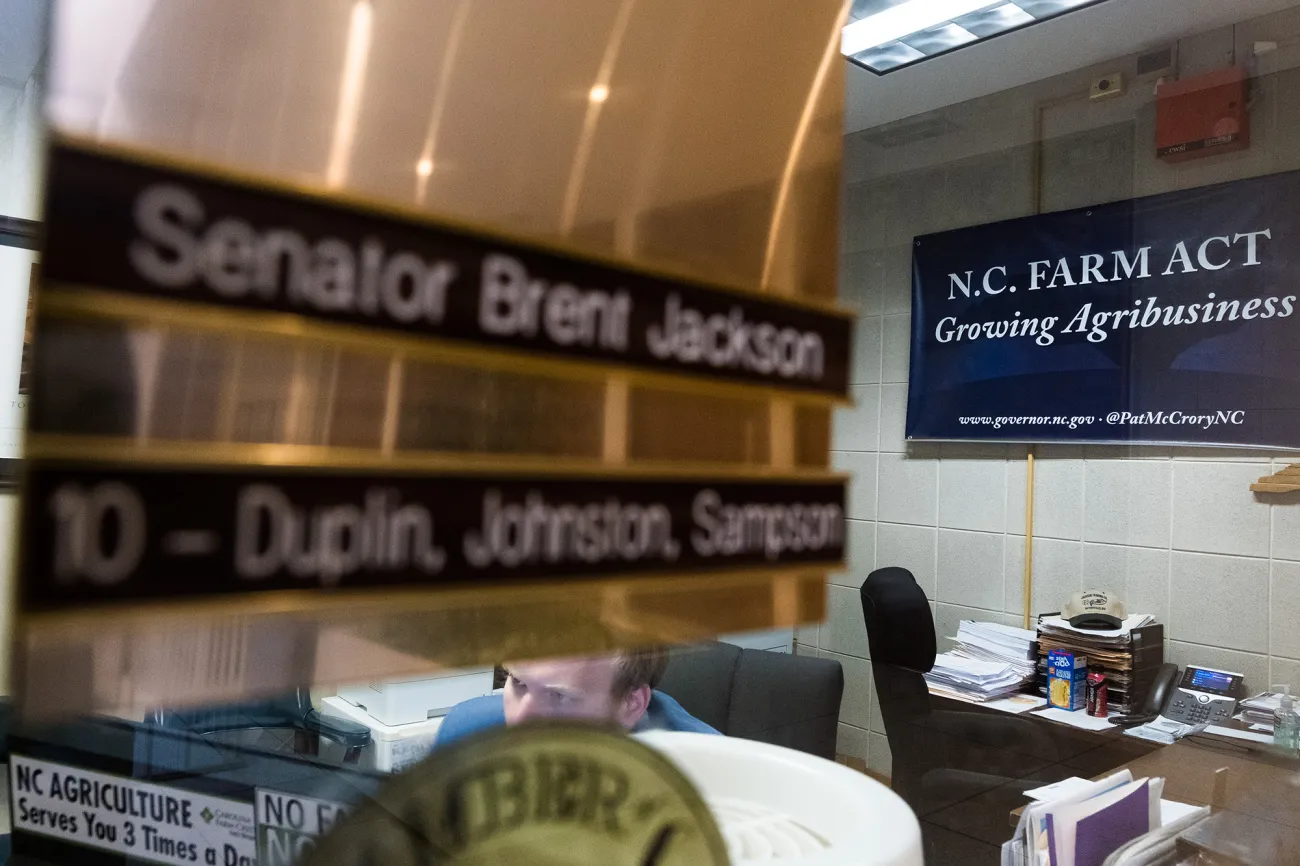

A North Carolina Farm Act banner hangs in the staffer area of Brent Jackson’s office in the North Carolina Legislature.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Jackson has thrown his weight behind other bills that have affected farm workers. As chair of the North Carolina Senate appropriations committee, he oversaw drastic cuts to the budget of Legal Aid of North Carolina, whose lawyers have been instrumental in representing the state’s farm workers, including against Jackson. The cuts forced the group to lay off up to 30 of its lawyers.

And last year, he was the co-sponsor of a bill that would have attempted to shield employers from being sued for retaliation by employees – the type of claim he himself has faced. The amendment was widely criticized and he later softened the language of the bill.

This has all been a part of what McMillan points to as a culture of anti-unionization in the state.

“There’s legal challenges. There’s cultural barriers, as well, in North Carolina,” she said. “There’s a lingering culture of fear about unions and stereotypes and misinformation that I think sometimes makes it difficult to organize.”

In her view, it has become more difficult to organize in North Carolina since Republicans took control of North Carolina’s general assembly in 2010: “We’ve definitely seen more anti-workers laws or bills proposed.”

Facing the future

In recent years, Reynolds American has acknowledged the importance of farm workers having the freedom to join a union. The company has enshrined in its supplier code of conduct a minimum set of standards, including a safe environment and freedom of association for workers.

“At least now they will admit that they have some responsibility to the workers in their supply chain,” Flores says. “After years of pressure, they’ve kind of come from ‘not our problem’ to ‘well, it is our problem’.”

Despite this, Reynolds has supported politicians and organizations who have pitched farmers against the union. “There are predatory folks that make a good living coming around and getting people to be dissatisfied,” one lawmaker and Farm Bureau ally said in support of the 2017 Farm Act.

This campaign against farm workers unionizing has come at a time when more and more growers are relying on the H-2A scheme, particularly since the Trump administration’s attempts to crack down on undocumented workers (who account for more than half of the nation’s farm workers, according to some estimates). Despite the feelings in political circles, Lee Wicker, the director of the North Carolina Growers Association told the Bureau that its collective bargaining agreement with FLOC largely succeeded. It gives workers a way to raise issues and for farmers to find solutions without the expense of going to court, he explained.

“I think it’s working,” Wicker said. “Naturally there’s tensions that arise but, for now, our growers have decided that this is the preferable way to resolve issues.”

Wicker points to other, more pressing issues facing farmers, namely an inability to plan future labour costs. Farmers do not find out the set wage for the following year’s H-2A workers until November, just months before many start arriving.

Growers also feel squeezed by cigarette makers, who grade and set the price of tobacco once it is grown and harvested. Tobacco companies can “come up with anything they want as an excuse not to buy your crop and if you don’t have insurance you get nothing,” one North Carolina farmer who supplies a subsidiary of Reynolds American told the Bureau.

A tobacco field in Sampson County, North Carolina.

Cornell Watson for Mother Jones and TBIJ

Tobacco can now be sourced more cheaply outside of the US, in countries such as Zimbabwe and Malawi, and prices in the US have not matched the increase in labour and production costs. A crop that for so long paid the bills for American farmers is now in steady decline. In 2020, the trade war with China—a major market for North Carolina’s tobacco—saw the state’s production sink to its lowest level in nearly 100 years.

For now at least, the harvest continues. Some farmers fear that this summer may be their last growing the crop that once shaped life in the state. Many have stopped already. But as per the last seven years, Carlos is back from Mexico, the temperatures already reaching record highs.

“It’s very hard work here in the fields—we feel the extreme heat,” he said in the shade on that Sunday in June, as he swiped through photos of his daughter’s drawings. But he and his fellow farm workers are allowed more breaks when necessary. “I like it where I am,” he says.

Roberto returned to North Carolina, too, and chuckled when asked if he would ever work for Jackson again: “I don’t think he’d take me back.”

Meanwhile, Jackson is seeking re-election in November. His campaign has already raised $600,000, more than almost every other candidate in the state. Much of this support is from industry groups and big business. He’s running unopposed.

“If I don’t die or go to prison and I can go vote for myself, I should be OK,” he joked on the podcast.

Last year, in a letter seen by the Bureau, Reynolds American told farm workers’ rights campaigners that “BAT and RJ Reynolds agree with you: Employers must not retaliate against workers for exercising their rights”.

In April this year, the company wrote Jackson another check.

Our reporting on tobacco is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders. Our Big Tobacco project is funded by Vital Strategies. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.