The United States guarantees 7.2 million students with disabilities an equal education. But the system is broken. For this package, we spoke with students, parents, teachers, and advocates about the dire state of—and efforts to fix—programs for students with disabilities. You can read all the stories here.

For the past nine years, Janet Kim has been feeding the pipeline of teachers for students with disabilities in Hawaii. As a recruitment specialist for Oahu’s University of Hawaii at Manoa, Kim’s job is to sell teachers on working with students who have cognitive, behavioral, and physical disabilities. “At first, it was really, really hard,” she said. “Anytime I would talk to people and mention Special Education, their reaction was, ‘Uh, no.’”

The data collection, reporting, meetings, and paperwork that make up an Individualized Education Program—which is federally mandated for every student with disabilities confirmed to require services—can seem like a part-time job grafted onto an exhausting full-time job, yet teachers for students with disabilities are typically paid no more than their general-education counterparts.

Perhaps that helps explain why 46 states have shortages of teachers for students with disabilities. Some of these shortages, including Hawaii’s, stretch back to the 1990s, and are higher, at 45 percent, than general-education teacher shortages, which were at 31 percent last year. The pandemic only worsened the situation.

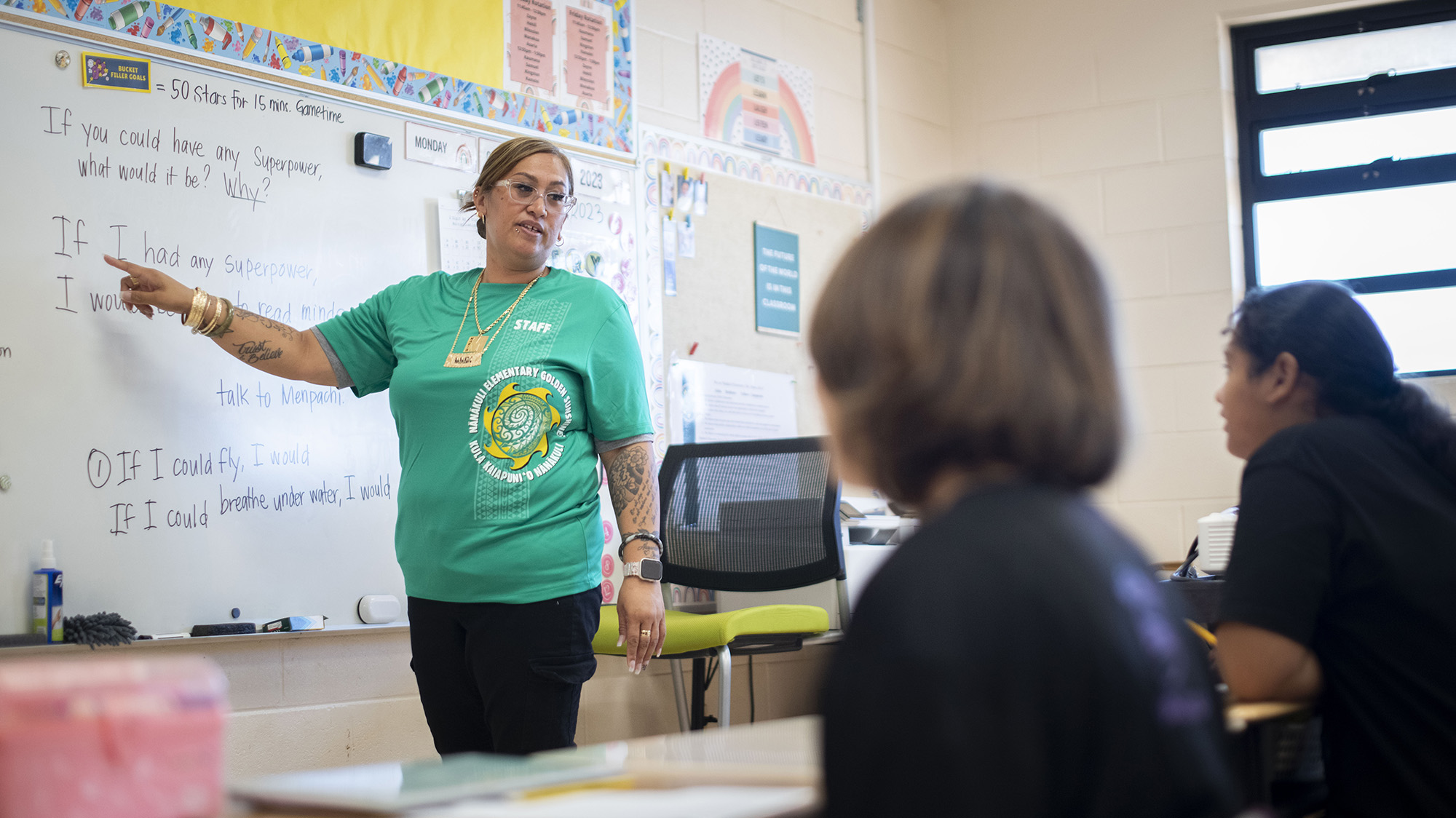

In Hawaii, the challenges of recruitment are more pronounced than elsewhere in the country—it’s a remote archipelago. It’s also expensive. Christina Keaulana works in recruitment of teachers for disabled students at Leeward Community College. Every year she watches new recruits come from thousands of miles away, only to leave by the end of the year. “They see that the cost-of-living index is twice that of the national average, and they can’t survive,” she said.

Christina Keaulana at Nanakuli Elementary School.

Elyse Butler

Hawaii is unique in another way: “We’re the only state in the country that operates as one school district,” Keaulana said. “Which means when we want to try something out, everybody’s on the same page, and we know it’ll be equitably applied across the state.” And over the last few years, Hawaii has harnessed this advantage.

In 2018, the Teacher Education Coordinating Committee—made up of an array of stakeholders, including the teachers’ union, a representative from the teacher standards board, the superintendent of the Department of Education, and each state-approved educator preparation program—worked to create a five-year retention plan. (Both Kim and Keaulana joined TECC in 2017.) “The government basically said everybody involved in education in the state of Hawaii needs to come together and talk about the Special Education shortages,” Kim recalled.

The TECC recommended a substantial raise for such licensed teachers: $10,000 per year. Some general-education teachers initially balked. “The raise was nice, but it did cause some discord with other teachers,” said Greg Volpone, an 18-year veteran of teaching students with disabilities on Oahu. “The question was, ‘Why are you getting paid more and we’re not?’”

Nevertheless, the plan was green-lit in January 2020, despite a lack of funding, in the hope that enough people would apply to get the state to allocate funding for it.

The new policy also includes an $8,000 increase for teachers in Hawaiian immersion schools and $3,000 to $8,000 for teachers in “hard-to-staff” locations. Multiple pay differentials can even be stacked: If a teacher is working with students with disabilities in a Hawaiian immersion school or hard-to-staff location, the teacher could earn as much as $18,000 more per year.

The raises were implemented at the beginning of 2020, and funding by the state was finally secured two years later, adding more than $34 million into the state Department of Education’s $2.1 billion general operating budget.

The risk paid off—the first analytical report on the new policy found the raises reduced vacancies for teachers of students with disabilities by 32 percent. And since schools were restricted to licensed teachers, the policy also reduced the number of unlicensed teachers by 35 percent.

“A lot of other states are reaching out,” Kim said, “because we’ve done some things that a lot of other people have talked about doing.”

Less than a year after Hawaii implemented the raises, Detroit Public Schools started offering a $15,000 pay differential for teachers of students with disabilities. In Atlanta, new Special Education program teachers were offered a one-time $3,000 hiring bonus, and all such teachers were offered a $3,000 pay differential, stackable with a second $3,000 differential for hard-to-staff schools. Atlanta Public Schools, like Hawaii, initially improvised the funding before getting it added to the budget to ensure long-term stability for the raises.

“We had 21 vacancies in Special Education,” said Nicole Lawson, chief human resources officer for Atlanta Public Schools. “We implemented the hiring incentives, and in two weeks, we filled all 21 spots. It was a game-changer.”

Across the country, the average school district puts about 80 percent of its budget toward teacher salaries, according to Heather Peske, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality. “We need to be more strategic about our use of teacher salary dollars,” she said. A starting point, she suggests, is eliminating the raise that many districts, including Hawaii, provide for the acquisition of a master’s degree. “There’s not a correlation in the research between having a master’s degree and being an effective teacher,” she said. “And yet that’s where millions go each year.”

Eliminating the estimated $4,000 pay bump that Hawaii pays all teachers with a master’s would generate about $18 million to help continue funding the pay differentials.

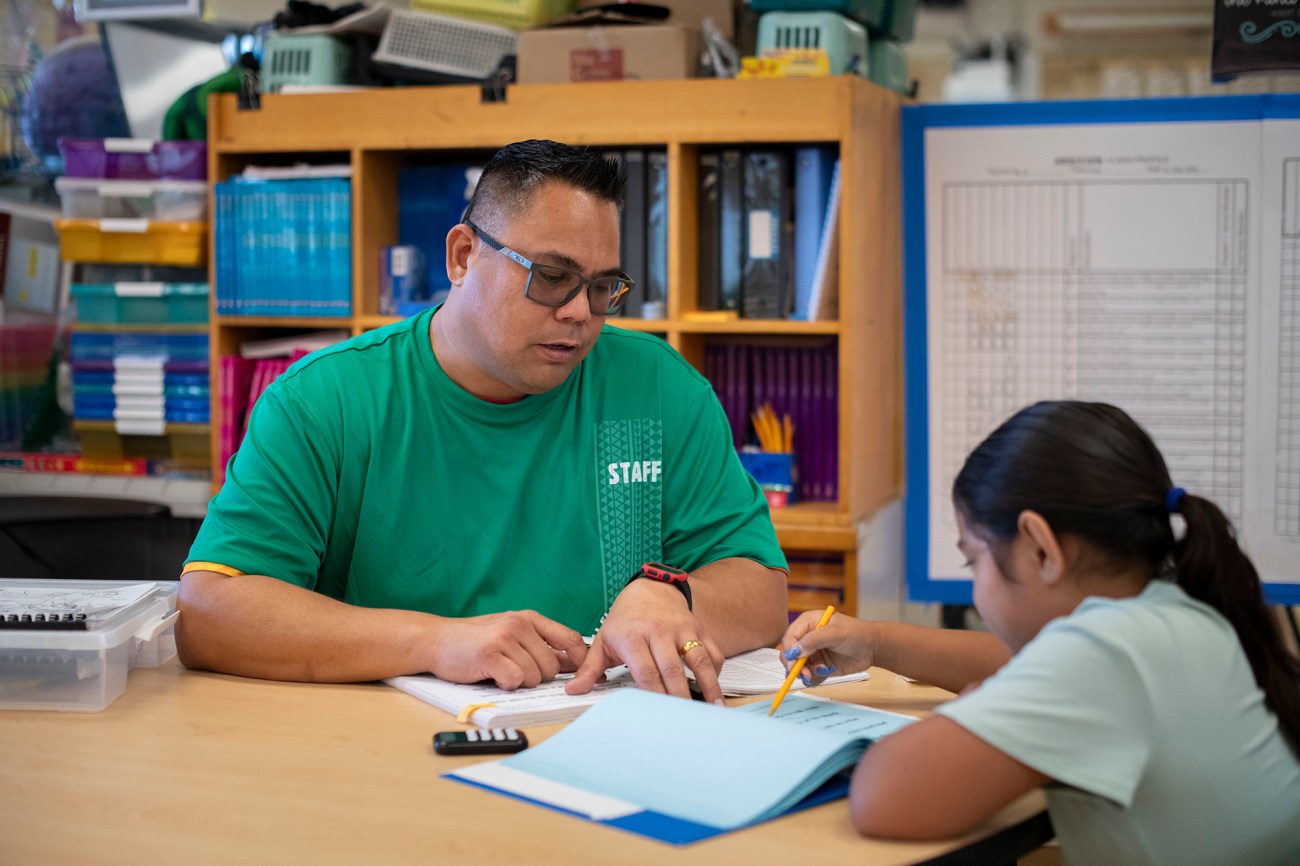

Education assistant David DeMotto works with a child at Nanakuli Elementary School, where the training program for teachers of students with disabilities began in Waianae, Oahu.

Elyse Butler

“Should states shift the policy and stop paying teachers more for a master’s degree—which often means that the teacher will acquire more debt—and instead use those dollars to pay teachers who teach in the schools and subjects where we need them the most?” asks Peske. “It seems like something worth considering in order to help fund these differentials that we see making a big difference when it comes to Special Education teacher recruitment.”

But it’s one thing to get qualified teachers through the door. Keeping them from getting discouraged is another matter.

“It’s significantly more work,” said Keaulana. “Classroom management-wise, you don’t have a single lesson that you design for a classroom of students. By the definition of Special Education, they are receiving an Individualized Education Program—that’s what an IEP is.”

Creating an IEP means writing out a precise learning plan for each student and coordinating regular meetings with several stakeholders—parents, administrators, support staff, fellow teachers—to articulate, execute, and monitor the plan. “I think Special Education teachers get really burned out when they feel like they’re not making a difference in the classroom because they’re having to spend so much time on the case-management side,” said Kim.

A common refrain among teachers of disabled students: Robust administrative support is essential for retention. “The money is definitely helpful but I also feel like the environment that the principal creates and the school culture that the principal creates may have a bigger impact on retention,” said Leimomi Kaaihili Leong, who was motivated by the Hawaii pay raises to obtain her licensure to teach students with disabilities in 2020. “When a teacher feels valued and appreciated and not overworked, meaning their work load is carried by many, it allows teachers to work longer.”

Director Keoki Fraser is in his first year at Kaohao Elementary, a public charter school in Kailua. “Honoring a teacher’s prep time has to be a top priority,” he said. This means making sure their teaching schedule isn’t overloaded, which sometimes requires creative solutions: “If I have a vice principal, for example, and there was a shortage in the department, maybe a vice principal can step up and teach some blocks. You have to look at all those options.”

Educational assistants—who work in the classroom under the supervision of a Special Education program teacher—can help offset that fatigue and increase retention. But few schools in Hawaii already have sufficient support staff in place. “We have four EAs,” said Volpone, speaking about Kalakaua Middle School, where he teaches. “We should have eight—at least.”

Christina Keaulana meets with education assistants Maria Manandic and David DeMotto at Nanakuli Elementary School.

Elyse Butler

Volpone said it’s not just the shortage of EAs but also the way their non-union positions are structured, often with limited hours. “The school wants people to come in and work 19 hours a week for $17 an hour, and they don’t want to give them insurance,” he said, pointing out that at 20 hours per week, EAs would receive insurance. “The EAs are really important to a successful classroom. How many responsible adults are walking around saying, ‘No, I don’t want insurance. Nineteen hours at $17 is plenty’? It doesn’t happen. There are restaurants in my neighborhood hiring dishwashers for 22 bucks an hour.”

Strengthening these support positions might not only help retain teachers but also improve the pipeline. Competent candidates are often already working as EAs but sometimes don’t see themselves as candidates. “EAs I spoke to in Native Hawaiian communities told me that, when they grew up, they saw the brown auntie as the helper and the white or Asian teacher as the lead,” said Keaulana. “They told me, ‘We don’t see ourselves as being in that position of authority.’”

Overcoming this bias is a big part of Keaulana’s work, as she encourages successful EAs to transition to licensed teaching positions. “These are candidates who are very rooted, whose families have been in the community for many years, if not generations—that’s who you want to target. They have the cultural knowledge to serve a unique community. They just don’t have the piece of paper that licenses them to become Special Education teachers.”

To help with that, Leeward Community College, where Keaulana works, has established scholarship funds for certification programs. The college also ran a pilot program in the Native Hawaiian community of Nanakuli that brought certification course work to candidates already working as EAs at a local elementary school, saving them the trip to campus. This localized approach to recruitment has been in place for nearly five years. Eighty-six percent of the program’s alumni are still in classrooms, compared with the state’s 52 percent retention rate for new teachers. Similar programs are in districts across the country.

“We have to grow our own,” said Felecia Lester, executive director of talent management and career development for Atlanta Public Schools. When the district recently reached out to EAs who already had a bachelor’s degree, 58 percent expressed interest in getting licensed. “And we’re training principals, saying, ‘You’re hiring paraprofessionals [EAs] with the idea that you’re building your pipeline of Special Education educators within your school because they already know the culture of your school and they already know the students.’”

Getting EAs and other candidates through the licensure process remains a challenge. While licensing is crucial to teaching quality, there are calls to reevaluate the basic content-knowledge test required for certification of teachers of disabled students in the state. “We know this test is culturally biased,” said Keaulana. “There’s a much higher percentage of [people of color] who take the test who fail.”

Leeward College and other licensure programs in Hawaii spent a year and a half in discussions with the state standards board to approve an alternative of 30 college credits of Special Education course knowledge. It adds more work but the road to completion is much clearer for many candidates. “That’s a huge barrier removed,” said Keaulana.

Alternatives to content-knowledge tests have popped up in other districts too. “In Atlanta, we had a lot of African American male paraprofessionals with bachelor’s degrees who simply could not pass the skills test,” said Lawson. “Many of them hadn’t taken a standardized test in years, and of course we know there are some cultural biases in these tests. So, we want to make sure we’re giving them every opportunity to pass with whatever support they need.” She said the district provided a bootcamp-style prep program that yielded a 99 percent passing rate.

Christina Keaulana and education assistants Maria Manandic and David DeMotto.

Elyse Butler

Another reform Hawaii is considering is ending the barrier—common in many districts—that prevents candidates from teaching in paid positions while completing their student teaching or clinical practice. “You expect people to go without pay for a year while they’re student teaching?” said Keaulana. “That’s ridiculous.”

Heather Peske said the NCTQ supports the idea of allowing student teachers to work in paid positions. “It’s very promising when districts are offering candidates with opportunities to complete their clinical practice while also getting paid,” she said. “When it comes time to find placements for clinical teachers, some of the smartest principals I know say they think of it as building their farm team.”

When it comes to Hawaii’s approach, Janet Kim returns to the importance of TECC, the state-mandated committee, and the sense of collaboration that defined its strategy to improve pay, train up, and scrutinize the licensure process. “It’s important to have every stakeholder at the table,” she said. “The only way we’ll make a difference is collaboratively and comprehensively.”

Correction, December 7: The headline on this story has been updated to reflect the terms of the $10,000 teacher raises.

Read the rest of our package on the state of education for students with disabilities here.