The United States guarantees 7.2 million students with disabilities an equal education. But the system is broken. For this package, we spoke with students, parents, teachers, and advocates about the dire state of—and efforts to fix—programs for students with disabilities. You can read all the stories here.

“What did you learn today?” Kary asks her daughter Liza as the 13-year-old waltzes into the kitchen of their second-floor apartment in the Bronx. (Kary requested that her real name and those of her family members not be used to protect their privacy.)

“I learned figurative language,” Liza says, “even though we already know what that is.” Nine-year-old Bella, the youngest of three children, jumps in excitedly: “Figurative language? Me too!”—confident in her mastery of hyperbole and other figures of speech.

Liza also had a lesson about planets, and Kary starts quizzing the girls. How many moons does Jupiter have? What about Neptune? Which is closer to Earth: Venus or Mars?

“Está bien—A+,” Kary says, satisfied with their answers. Then comes her final question: “The sun, is it a planet or a star?” Liza hesitates before guessing the former, and Kary promptly corrects her. “I knew it!” exclaims Bella, whose single braid trails down to her hips.

“Qué quieren comer?” Kary asks. “What do you want to eat?”

There’s hardly an empty surface in the cluttered but neat apartment. Dozens of bottles of perfume and body lotions that Kary sells for extra cash sit on dressers in the corridor and in the girls’ bedroom, which they share with their mother. Rolls of yarn she shapes into intricate crochet designs overflow from drawers. Next to the girls’ Komi Can’t Communicate books—about a high schooler who struggles with social anxiety—are wooden lacing shoes and a fidget-toy kit.

On the fridge are two photos of Cristobal, Kary’s oldest child and only son, who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder as a toddler. He is 14 years old now, and even though he is nonverbal, he is very clear about his preferences. He doesn’t like the heat, so he turns on the air conditioning even during the winter. He hates clothing tags and sleeping in the dark. He loves playing with water, watching Fireman Sam and Blue’s Clues, and sugary drinks. In a picture from 2017, a boy with short dark hair who is dressed in a plaid long-sleeved shirt stands next to letters of the alphabet with the word “mama” spelled on a classroom blackboard. “He’s beautiful,” Kary says.

She tells the girls to take out the trash as she goes to tidy up Cristobal’s bedroom before he comes home from his small ninth-grade class at a Long Island specialized private school. With tuition paid by the New York City Department of Education, he receives instruction based on Applied Behavior Analysis to improve social skills and encourage independence, as well as speech and occupational therapy, and is entitled to an additional 10 hours of home-based ABA weekly. Kary has been looking for a provider for that service for four months now.

Kary and Cristobal work together on his homework Saturday afternoon in their apartment in the Bronx.

Lexi Parra

Kary knew early on that Cristobal would need extra care. At 11 months old, he started having seizures and stopped laughing or responding to any stimulus. After Cristobal didn’t meet certain milestones—crawling, for instance, and talking—the pediatrician recommended therapies to address speech and motor skill delays. Before he turned 2 years old, Cristobal was diagnosed and began to receive support at home through the early intervention program run by the city’s Department of Health. By the time Cristobal was in kindergarten, he could read, write, and say his “ABCs” and numbers from one to 20. His speech therapist identified signs of echolalia, when the child repeats a few words and sounds they hear around them.

But the public education system for students with disabilities would fail him. In first grade, while attending a specialized public school, Cristobal regressed significantly and started having tantrums. In fourth grade, he came home with bruises on both arms. Kary says she never got any explanation about what had happened, even after she reported the incident to the District 75 office. Cristobal’s tantrums grew more pronounced and his behavior more aggressive. His academic progress stalled. Knowing that her son could not advocate for himself, Kary continued to push for more services and support, but at school meetings she wasn’t given an interpreter.

Kary had moved to the United States from Mexico in 2005 when she was 15. She became involved with a man, with whom she would eventually have three children, but, shortly after they moved in together, he grew abusive. Kary worked hard to support her family, with jobs at McDonald’s, delis, as a housekeeper or babysitter. During one period, she spent 72 hours a week at a factory in Brooklyn making logos for hats. She brought that same determination to her campaign to seek essential educational services for her firstborn but encountered obstacles at virtually every step of the way. “They make us feel guilty,” Kary says, “like we’re doing everything wrong, or we’re not doing enough.”

Securing the best school setting for Cristobal was especially hard when Kary was still learning English. New York City is home to the largest school system in the country, and it is also where one in five students, or more than 280,000 kids, have a disability. Navigating the gauntlet of services for disabled students is often overwhelming for most parents. Those who do not speak English face even greater barriers.

Cristobal lays down on a rock in the park near his home on a Saturday afternoon. He didn’t sleep much the night before after refusing to take his medicine, so he wanted to rest.

Lexi Parra

“Before the child gets referred to Special Education, it can be two or three times harder for the parent to notice the disability,” explains Minjung Jin, a staff attorney at New York Legal Assistance Group, a nonprofit providing free legal services to the city’s residents. She has been working with Cristobal and his family since 2021. “They might not have access to progress reports in their language, and they might not be able to speak to the teacher as frequently as English-speaking families.”

Kary keeps a storage container in the apartment with all of Cristobal’s Individualized Education Program reports—legally mandated roadmaps outlining the student’s unique strengths, needs, and goals—from his years in the public school system. None are in Spanish. She did her best to communicate her concerns to the English-speaking school administrators, but they were dismissive. Worried that Cristobal was being physically abused and having lost confidence in the public school’s ability to educate and care for him, Kary decided to seek help elsewhere.

“I didn’t know anything about the school system,” she recalls. “I didn’t know there are attorneys who can fight for my son’s rights.”

But then, in 2016, a worker with the Administration for Children’s Services in charge of Kary’s domestic violence case pointed her to the Bronx Family Justice Center, which helps survivors. They referred her to NYLAG, and, with an attorney’s counseling, Kary applied for legal status under a special visa for victims of crimes and got a work permit. (She has won custody of the children and an order of protection against her former partner.) Two years later, she connected with the group’s unit for students with disabilities to address Cristobal’s unmet needs.

“I finally found a light on my path,” Kary says, “because it was really dark.”

Kary poses for a portrait in the park near her home in the Bronx.

Lexi Parra

Kary’s fight for Cristobal’s education is a familiar one for Melinda Andra, director of the Kathryn A. McDonald Education Advocacy Project at the Legal Aid Society, which is charged with advancing the educational rights of New York City students, including those in child-welfare proceedings. “The additional barrier of language is like another wall that somebody put in front of you,” she says.

One problem is the shortage of bilingual evaluators to determine if a student is eligible for services, which means many families are waitlisted. Unless, that is, they can afford an independent bilingual evaluation, which can cost upward of $7,500, or if they have access to legal help to make the DOE pay for one. Parents like Kary have the right to request interpretation for IEP meetings, where the students’ annual goals and recommendations are discussed. Sometimes the school sends a staff member who might speak the language but is not a trained interpreter, or the school might not offer one at all. Different lawsuits filed on behalf of non-English-speaking parents of students with disabilities over the years have noted a persistent pattern of language-access violations by the DOE, including failure to provide translations for a wide range of critical educational assessment documents. In some instances, parents were kept in the dark about medical issues and bullying incidents. The DOE has made efforts to improve the translation process, but advocates say the improvements are inadequate.

Lack of access to information about a student’s progress and wellbeing can be particularly troubling for parents whose children, like Cristobal, are nonverbal and can’t clearly communicate as to whether they have received services. “That is happening every year,” Jin says. “Basically, they are being excluded from discussions about their child’s education needs.”

Jessica Selecky, the director of NYLAG’s Special Education unit, recalls the case of a family of impoverished asylum seekers who spoke a less common African dialect. Every time the parent, who was illiterate, attended an IEP meeting at the school for the student with an intellectual disability, the interpreter spoke a different language from that of the parent. During the Covid pandemic, the teenage student was given a tablet, but the shelter where the family lived didn’t have internet access.

Eventually, Selecky managed to win him compensatory tutoring services, and the DOE agreed to pay for a nonpublic school placement. But the parent’s phone line kept being shut off, and she couldn’t visit the schools or missed the calls to schedule the intake process. Feeling discouraged, the student considered dropping out of school altogether and finding a job instead. He has since used some tutoring services but stayed in a public school. Those are the cases that keep Selecky up at night. “We’re just lawyers,” she says, resigned. “All I can do, I’ve done.”

With the recent arrival of thousands of asylum seekers and 20,000 new migrant students enrolling in New York City schools, Selecky worries they might not have had access to programs for students with disabilities in their home countries and might not be aware of their rights. “We haven’t seen the increase, but we know [the demand] has to be there,” she says. The main challenge is how to reach them. So Selecky has partnered with other NYLAG units to develop a know-your-rights workshop focused on accessibility in education in hopes of identifying eligible students, while giving parents basic information about the system. “We do this work on the front-end,” she says, “hopefully to save loss of learning.”

On an unseasonably warm Monday morning in October, Jin joins NYLAG’s Special Education unit meeting at their office in Lower Manhattan. The conference rooms are named after writers Elie Wiesel and James Baldwin, and the walls are covered in quotes about justice and equality. “Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble,” one from civil rights icon John Lewis reads.

Jin, wearing a dark green shirt and mustard-colored pants, is part of a five-person legal team. Sitting at the end of a conference table next to Selecky, while the others join via Zoom, she speaks quietly but assertively as they discuss a conflict with the DOE over the placement of a boy on the autism spectrum who could use home instruction to graduate from high school. Next, they talk about a seventh-grader with dyslexia who needs a transfer to a specialized private school.

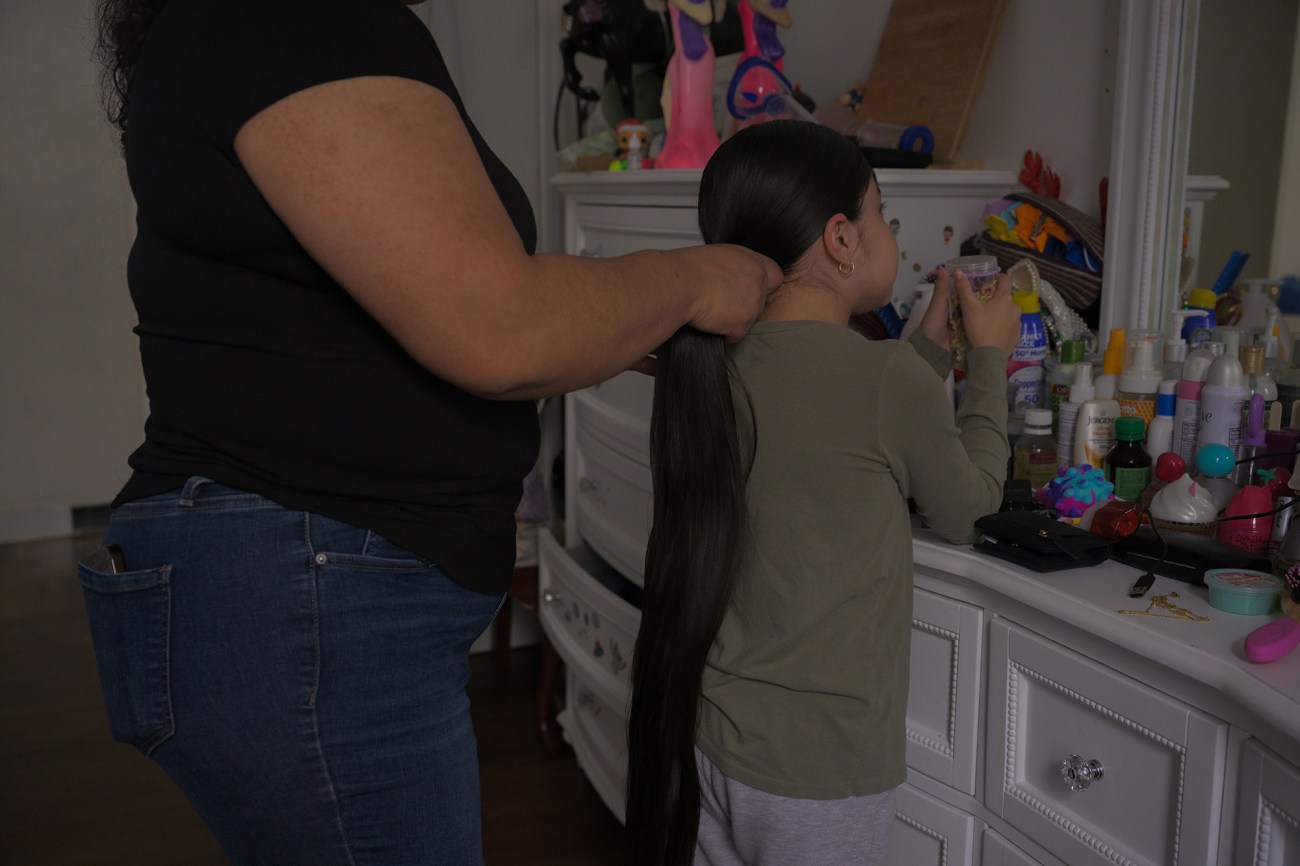

Kary braids Bella’s hair in the bedroom that Kary shares with her two daughters.

Lexi Parra

NYLAG fits into a small universe of about five or six legal aid organizations with units specifically serving families of city residents with accessibility needs, Selecky says. Each attorney works on about 20 cases at any given time, in addition to providing limited advocacy and counsel for several others. Clients reach the organization mostly through referrals or the recently reopened intake phone line for the unit specializing in students with disabilities. Of the 364 calls that came in so far this year, 142 cases could have benefitted from representation but the unit did not have sufficient staff to take them all on. And the families who know to call, likely through word of mouth, are but a fraction of those who could use the help.

Most families seeking assistance from NYLAG’s specialized unit are low income and often deal with issues related to housing, immigration status, and health care. By the time clients connect with the group, all other options to enforce their children’s rights under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act for a “free appropriate public education” in the least restrictive environment have been exhausted.

Filing a due-process complaint and seeking an impartial hearing is often families’ only course of action. In the 2022 fiscal year, 15,880 such complaints were filed against the DOE, according to a city comptroller report. The city’s spending for claims related to disabled students’ education services increased more than tenfold, from $33 million to $372 million between 2012 and 2022. The DOE projects at least 20,000 new claim filings in fiscal year 2023, requiring more than $1 billion to address complaints.

The comptroller’s report also found that IEP-related service recommendations were more likely to be unfulfilled or only partially fulfilled in the city’s predominantly Black and Hispanic school districts. Bilingual students are especially underserved; 64 percent of disabled students entitled to bilingual education didn’t receive all their mandated services in the 2021–2022 school year, compared with 12 percent of all students with IEPs.

“Every student deserves to get the help they need to succeed in school in their own language and without leaving the community,” Nicole Brownstein, a spokesperson for the DOE, said in a statement. “As with all New York City Public Schools programs, translation and interpretation services are available for all families.”

In 2020, NYLAG filed a class action lawsuit, still ongoing, claiming families of children with disabilities had to wait on average more than three times longer than the mandated 75 days for a decision on due-process complaints. The city’s DOE and the New York State Education Department denied the allegations. Even when families do win their cases, the process can drag on. This past summer, a federal judge mandated that the DOE address delays in providing education services and payments to families and required the city to implement dozens of recommendations, including hiring additional staff and setting up a support hotline for parents.

“The new requirements are stringent because we, too, believe that change is long overdue,” Chancellor David C. Banks said in a statement. The ruling has been lauded as a promising step toward improving a burdensome system. But some, such as Andra with the Legal Aid Society, are skeptical it will help families with the least resources, including non-English-speaking parents. The judge’s order comes in a case that specifically addresses the tail end of the process—that is, compliance—and covers those who have already managed to win favorable decisions from hearing officers in their payment or services disputes with the DOE. Parents with limited English proficiency, she says, are “fighting to even get basic things” like evaluations and translated documents and “struggle to get to that point where they even have an [impartial hearing officer] order to get complied with.”

On a Wednesday in October, Jin arrives at the office before 9 a.m. to prepare for a pre-hearing call. She meets with Kary, who is dressed up in all black and high heels and gives Jin a crocheted sunflower and white roses bouquet. Kary tells Jin about Cristobal’s progress, and Jin pulls out her phone and plays a recording of Cristobal interacting with a calendar on a screen. When he picks “Friday” as the day of the week, the prompt says, “Great job!”

For Jin, the work feels personal. Born in South Korea, she moved to New York in 2013 to attend law school. After starting an internship with NYLAG in 2020, Jin realized how she could have helped her sister-in-law who has Down syndrome and whose parents didn’t speak English. All the information they received about their daughter, who was placed in a big classroom without a bilingual instructor, was through a Korean-speaking paraprofessional. Any assessment she underwent focused on academic improvement, even though the parents’ goal was to foster independent living. Today, Jin’s 25-year-old sister-in-law struggles with cognitive, communication, and emotional regulation functioning delays. The rehabilitation programs she has access to through the state’s Office for People With Developmental Disabilities don’t make up for what she lost during a decade of schooling.

“I have seen what happens to a child if they do not get appropriate education during their time in the public school system,” Jin says. “My goal is that it doesn’t happen to many children.” The most rewarding part of the job is witnessing the progress that students—some of whom she accompanied throughout their entire educational journey—make when they are finally placed in an appropriate classroom setting. When one of her clients was 13, he was able to say “I love you” to his mother for the first time. “That is the kind of thing that makes me work harder and stay motivated,” she says.

When reviewing Cristobal’s records, Jin saw that the DOE had failed to assess his communication skills and autism profile properly. NYLAG helped Kary obtain an independent neuropsychological evaluation that recommended all the services he needed. The DOE insisted on conducting its own assessment but agreed after an IEP meeting that a nonpublic school setting was his best option. Finding an appropriate state-approved nonpublic school that had ABA services and would accept Cristobal proved difficult, so Kary and Jin eventually settled on a school without ABA. Although a better placement than his previous public school, it was still an imperfect arrangement.

Cristobal plays at the playground of the park near his family’s apartment in the Bronx.

Lexi Parra

In September 2022, Jin filed a due-process complaint challenging Cristobal’s previous IEPs and listing several violations by the DOE over three consecutive years when he attended a public school, including failure to provide speech therapy one year and the recommended ABA. The complaint also addressed the absence of an interpreter at IEP meetings.

Then, earlier this year, administrators from Cristobal’s school told Kary she needed to contact the DOE and request a new placement. “Cristobal was having these big meltdowns,” Kary says, “and they were calling me every time to come and pick him up.” She recalls that someone from the school advised her to move Cristobal to a residential program with a more restrictive setting.

With Jin’s help, Kary found a private school that offered adequate services and accepted students whose families couldn’t afford the tuition. In May, a hearing officer decided on the complaint in their favor and ordered the DOE to cover the private school tuition and home-based ABA for the next three school years.

During the summer of 2023, Cristobal started at the new specialized private school in a six-student class with one teacher and a teaching assistant. Kary has already seen positive changes. He is participating in class and doing homework more independently. When the school calls these days, it’s to let her know that everything is under control. Before, she couldn’t play loud music in the house because it bothered him. Now, he listens to the Mexican singer Luis Miguel (but he doesn’t like when Kary sings along).

Kary points to a round-shaped hole on the bottom of the bedroom door. “Cristobal did it last Thursday,” which was, Kary says, “a really hard day for all of us.” Another crack is visible on the wall next to his bed where he kicked it.

Cristobal watches a television show on a computer in his bedroom.

Lexi Parra

Cristobal had been feeling sick for a couple of days, so he stayed home. By Thursday he was supposed to go back to school, but the paraprofessional assigned to accompany him on the bus and in the classroom overslept. Upset that he had to miss school, Cristobal started yelling and kicking. Kary tried to calm him down, but at 6 feet tall, he easily overpowered her. When his sisters arrived home from school, she had to lock them in their room to stop Cristobal from scratching and punching them. Sometimes when Cristobal is having a meltdown, Kary lies on the floor next to him until they’re both crying.

“I always say he’s my angel on earth,” Kary says. “He taught me a lot about life: to be patient, to be lovely, to advocate and raise my voice.” She describes all the positive changes he’s brought into her life: learning English, becoming more involved in school activities, getting her GED, and starting college before the pandemic so she can become a speech-language pathologist.

Today, the school bus arrives home around 3:45 p.m., and Cristobal, in a gray hoodie, jumps out and runs to the top of the street around Crotona Park, where he likes to climb rocks and ride a scooter. The paraprofessional tells Kary that Cristobal had a good day at school. “I will not give up on my son,” Kary says. “I’m going to help him until the end. I don’t know how I’m going to do it, but I will.”

Read the rest of our package on the state of education for students with disabilities here.