Modeling of Omicron strain of the virus (blue) and red blood cells National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/Zuma

On March 18, the Supreme Court will hear arguments on whether the federal government overstepped its bounds by asking social media companies to adopt stricter policies in removing misinformation related to COVID-19 and tools to minimize its spread, such as masking and getting vaccinated.

The plaintiffs—the attorneys general of Missouri and Louisana as well as private social media users—first filed the lawsuit, Murthy v. Missouri, in Louisana back in May 2022. They claim that the federal government violated First Amendment rights by “coercing” or “significantly encouraging” Big Tech to demote or remove social media posts on the basis of misinformation like linking mail-in voting to election fraud and claiming that COVID-19 originated in a Wuhan lab.

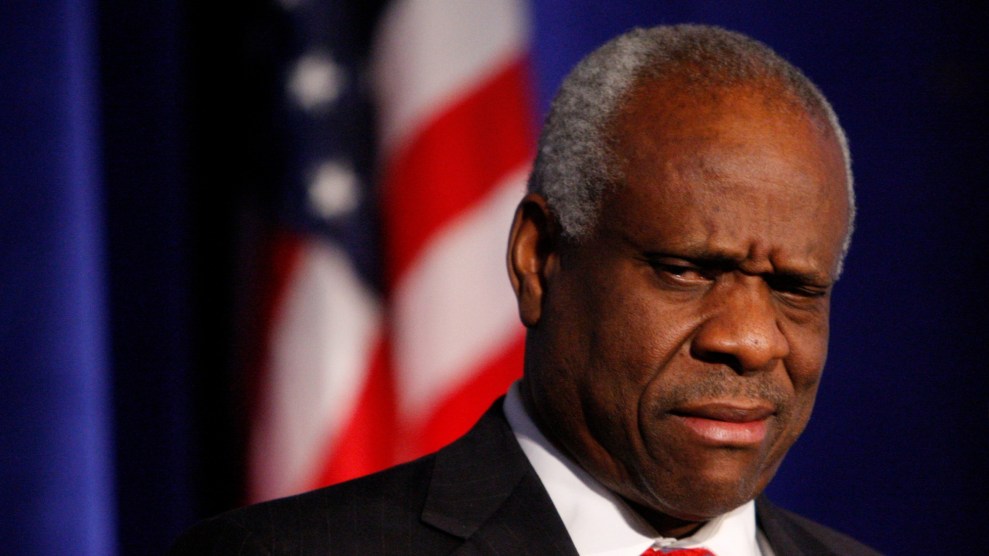

In July, the district court issued an injunction prohibiting the Biden administration from communicating with social media companies to remove “content containing protected free speech.” The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals later vacated much of the injunction, but agreed that some federal agencies took steps that may have violated the First Amendment by talking with social media platforms about their moderation decisions. Then, in October, the Supreme Court granted the government permission to keep corrsponding with social media companies until a decision was made, with Justices Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch dissenting.

Misinformation about COVID-19, largely spread on social media, has been as contagious as the disease itself. Research suggests that misinformation has contributed to people not getting vaccinated, refusing masks, and not taking medication that could reduce acute complications. Despite many politicians from across the spectrum referring to the pandemic in past tense, it remains a leading cause of death both in the US and internationally.

I spoke with Andrew Twinamatsiko, a director of Georgetown University’s O’Neill Institute Health Policy and Law Initiative, about why this case might be concerning from a public health perspective.

What’s at stake with the Murthy v. Missouri case?

What is at stake is an unprecedented weaponization of the First Amendment as a deregulatory tool that would hamper the government’s efforts to address misinformation in any meaningful way. Here, we have two Republican state attorneys general and social media users claiming that the government’s efforts to flag content that violates social media platforms’ own content rules are impermissibly coercive and violate the First Amendment. Let’s remember that is not a law that targets the specific content or viewpoint.

The government’s agencies, like the CDC, who have the expertise in these issues, identify the misinformation festering on social media and inform social media platforms why they should consider taking the information down. Social media platforms don’t have all the expertise to ferret out this misinformation, so it’s helpful to have the expertise of agencies like the CDC and the Office of the Surgeon General helping to shore up the efforts to combat the misinformation. The challenge, in this case, is akin to saying that the First Amendment prohibits the government from telling a manager of a crowded theater that someone in the audience is falsely shouting fire and is likely to cause a panic, so that the theater can take appropriate measures to address the false claim.

Does the federal government have any legal obligation to take steps to protect the health of US residents?

Yes, it definitely does. Protecting the health and welfare of the people is the primary reason governments exist. There is an old adage in public health—which ironically is the state motto of Missouri—that salus populi suprema lex esto, meaning that the welfare of the people should be the supreme law. This same idea was proclaimed at the nation’s founding when it was declared that “we the people” ordained and established the Constitution for the United States of America to provide for the common defense, and—wait for it—to protect the general welfare. And accordingly, the Constitution gives the federal government the power to protect the health of Americans through its power to regulate commerce, to tax, and, specifically, the spending clause says, “Congress shall have power…to provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.” And protecting the health of the people has been the very business of Congress—establishing Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, occupational safety, protecting against pollution, you name it.

Although the First Amendment puts limits on what the government can do, it’s been used in the extreme fashion that the challengers are following in the Murthy case. For example, in the ’60s, when the Surgeon General’s report showed the association between cigarette smoking and lung cancer, heart disease, and other diseases, cigarettes were required to bear information on the dangers of cigarette smoking. Also, federal law prohibits advertising cigarettes on radio, TV, and other media operated by the FCC. Drugs have to have warnings, food has labels to show the contents, and many others.

Are there other notable court cases that have pitted public health and free speech against each other, or is Murthy unique in this way?

This weaponization of the First Amendment in the health space is not surprising. The Supreme Court said that a California law that required pregnancy crisis centers to disclose truthful information about the services they provide violated the First Amendment. And just last year, the Supreme Court used the First Amendment to greenlight discrimination against sexual minorities, and potentially other protected groups, by businesses

You’ll remember the slew of cases that challenged states’ efforts to mitigate Covid contagion by requiring social distances in places of worship—on First Amendment grounds. Now we have pharmaceutical companies arguing that the First Amendment insulates them from negotiating the price Medicare pays for prescription drugs.

How could a decision against the government affect its ability to try and stop disinformation on social media in both the current and future pandemics?

It would put the US in an untenable position. In order to govern, the government has to speak. I don’t mean to suggest that the First Amendment isn’t a cornerstone of our democracy, but the liberty interests protected by the First Amendment aren’t a license for anarchy. If you follow this case, even through the discovery process, social media platforms, these are billionaires. They’re not to be bullied around by the government. They have declined some requests, like, “We’re not going to take that down.” There’s not a huge power imbalance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.