Ruby Bridges, the first Black student to integrate an elementary school in the South, thinks book bans are "ridiculous." Rogelio V. Solis/AP

Civil Rights icon Ruby Bridges is an integral part of U.S. history lessons in classrooms nationwide, given her status as the first Black child to integrate an elementary school in the South. But to the right-wing culture warriors behind efforts to ban books about American history—including systemic racism and discrimination against LGBTQ people—Bridges has become something else: a threat.

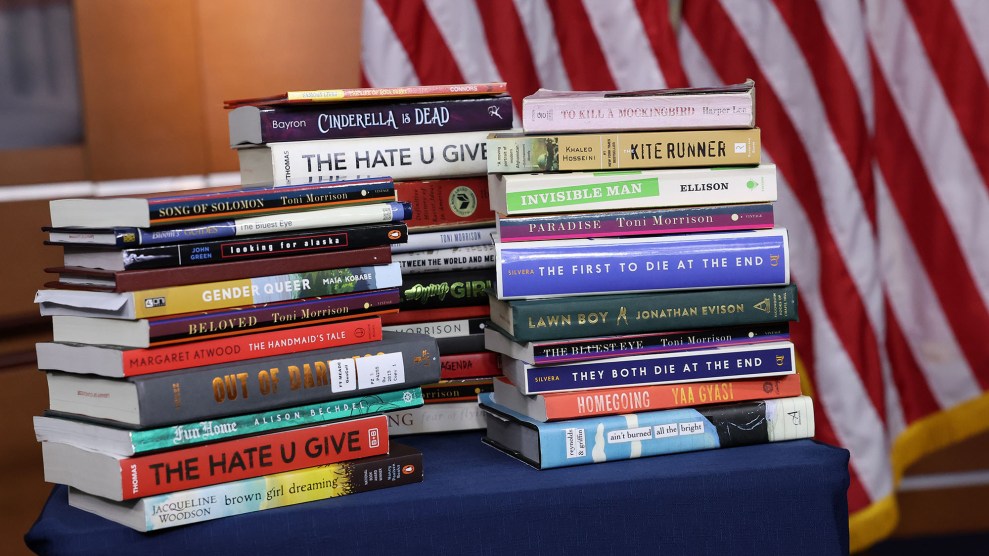

Books recounting Bridges’ story—several of which are authored by Bridges herself, including one published in January—have been banned or challenged by schools in Pennsylvania, Texas, Iowa, and Tennessee. And last year, a school in Florida stopped showing a Disney film about Bridges’ life after a parent complained it might make kids think white people hate Black people.

On Sunday, Bridges, 69, told Kristen Welker, host of NBC’s Meet the Press, that she sees such efforts as “ridiculous.”

“The excuse that I’ve heard them give is that my story actually makes, especially White kids, feel bad about themselves,” Bridges told Welker, adding that children from all around the world regularly reach out to her to tell her what her story means to them.

“I found through my 25 years of travel that they resonate with the loneliness, probably the pain that I felt, not having a friend,” she told Welker of readers. “There’s all sorts of reasons that they’re drawn to my story. So I would have to disagree…I believe that it’s just an excuse not to share the truth—to cover up history. I believe that history is sacred—that none of us should have the right to change or alter history in any way.”

WATCH: Civil rights activist Ruby Bridges reflects on book bannings, as her own work has faced censorship in some schools.

"I think that's ridiculous. I mean, most of my books have been banned. … It's just an excuse not to share the truth, to cover up history.” pic.twitter.com/HyvS2j3yR9

— Meet the Press (@MeetThePress) April 27, 2024

When Bridges desegregated her New Orleans elementary school in November 1960, she and her mother were escorted by federal marshals as crowds of angry white people screamed racist slurs. Some white parents withdrew their kids from the school in protest of her attendance.

“My parents never explained to me what I was about to venture into,” Bridges told Welker, adding she thought she was “venturing into a Mardi Gras parade” the first day she attended the desegregated school—a misperception she held until she met a child inside who called her a racist slur.

WATCH: Ruby Bridges made history when she attended a newly desegregated school in 1960 — but she didn’t grasp the full significance at the time.

“My parents never explained to me what I was about to venture into. … I thought that day I was venturing into a Mardi Gras parade.” pic.twitter.com/NytGarSdS3

— Meet the Press (@MeetThePress) April 28, 2024

The conservative group Moms for Liberty has led the charge to ban books nationwide, and several of its activists have deemed books about Bridges “inappropriate.” One of the group’s co-founders claims that the way one of the books about Bridges is taught—but not the book itself—is “divisive,” because a teachers’ manual directs teachers to mention a racist slur featured in the book.

But Bridges—and the majority of voters, 61 percent of whom oppose efforts to remove books from school libraries—disagree that “divisive” materials that depict accurate American history warrant censorship. “Those things are what we live with today,” Bridges told Welker. “The history, all the subject matter that they want to ban, it’s happening in the world. We cannot live in a bubble, put blinders on like it’s not happening…we’re not hiding anything from our young people.”