Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), one of the senators who introduced the "Build Green" Bill.Francis Chung / AP

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Although the nation has seen record federal investment in infrastructure under President Joe Biden, the majority of the funds are flowing to roads and bridges—not to projects that will clean up the transportation system, those tracking the spending have found.

In an effort to revive the original transformative vision that climate action advocates, including Biden, brought to Washington at the start of his administration, Congressional Democrats on Monday were set to introduce the Build Green Act, legislation that would invest $500 billion over the next 10 years in addressing the nation’s largest source of greenhouse gas pollution: transportation.

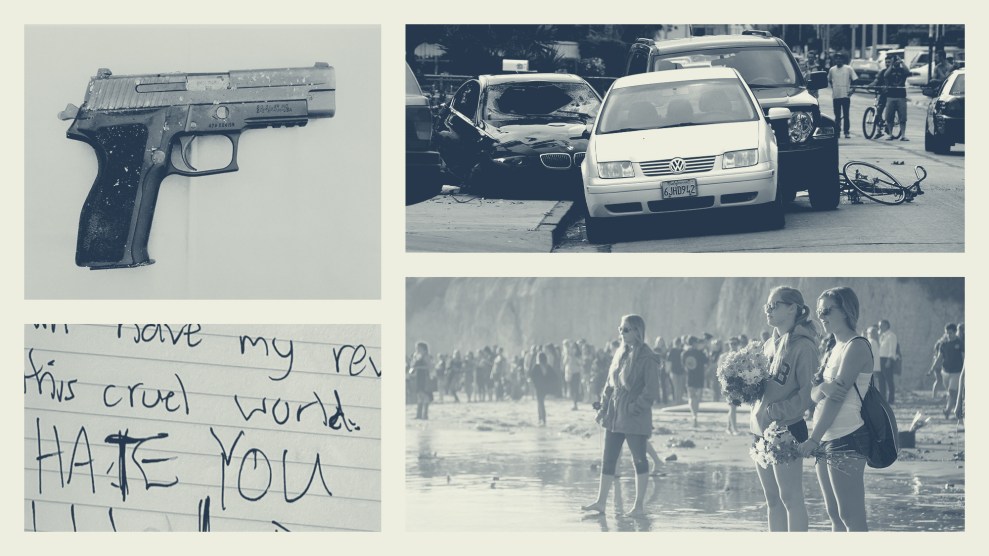

The transportation sector now makes up 28 percent of US carbon emissions, and there has been little progress in reducing that burden. Carbon emissions from transportation in 2022 were 19 percent higher than in 1990, and they fell less than 1 percent from 2021 to 2022, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“The time to accelerate towards a clean energy future is now,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who plans to introduce the new Build Green bill in the Senate. “Modernizing our transportation grid will pump billions into the economy, create green union jobs, and safeguard against the worst effects of climate change. That’s good news across the board.”

In the House, the legislation will be sponsored by Rep. Robert Garcia (D-CA), whose district includes the Port of Long Beach, one of the nation’s biggest shipping centers and a major source of pollution affecting low-income and minority communities.

The bill would resurrect much of the DNA of the $2 trillion “Build Back Better” idea that Biden touted on the campaign trail in 2020. Warren was the original sponsor of the Build Green Act introduced early in 2021, and it became part of the template for the bipartisan $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that passed later that year. (”Build Green” is an acronym for the bill’s full title: the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development and Generating Renewable Energy to Electrify the Nation’s Infrastructure and Jobs Act.)

But in order to win over the votes of Republicans and conservative Democrats like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.), clean energy investments were sharply cut and spending on repair and widening of highways and bridges were ramped up. For example, an originally planned $174 billion investment in electric vehicles and a network of charging stations was pared back to $7.5 billion for EVs, charging infrastructure and electric school buses in the final bill.

Of the $15 billion in spending so far under the 2021 infrastructure legislation, 35.5 percent has been directed to road and bridge projects and another 12 percent to airports, according to tracking by the National League of Cities. Only 19.6 percent of funding has gone to public transit systems. Many more projects have sought funding than could be covered under available dollars.

To address that shortfall, the new Build Green Act would allocate at least $150 billion for fixed-route public transportation projects like subways, light rail and bus rapid transit systems. That would be more than enough to fund the current full cost of every project on the Federal Transit Administration’s Capital Investment Program Dashboard—a regularly updated list of projects seeking funding.

Although the grant program the bill creates would fund all forms of transportation, the Department of Transportation would be directed to give priority to collective over individual transportation projects and to projects that reduce air pollution and greenhoe gas emissions.

Climate advocates argue that such an emphasis on green spending has been missing as DOT sends infrastructure funds to states, which largely are responsible for setting priorities. Projects like the Texas Department of Transportation’s proposed $12 billion widening of Interstate 45 in Houston would increase both emissions and environmental injustice, displacing 1,079 homes, 344 businesses and five churches, local opponents say.

Transportation for America, a public transportation advocacy group made up of state and local officials, has warned of a “climate time bomb” of 69 million metric tons of carbon dioxide that will be added to the atmosphere by 2040 based on current spending trends by state transportation departments.

“We actually need to make investments and create jobs in a new type of transportation system that’s primarily electrified and that is not making the climate crisis worse,” Saul Levin, legislative and political director for the Green New Deal Network, a coalition of climate and environmental justice groups. “This bill really gives us a sense of what’s possible in the future. I think it’s really visionary work to take the next steps even as we’re implementing the most recent investments.”

The new Build Green Act would allow DOT to fund up to 90 percent of the cost of projects, and would permit certain projects to be fully funded by the federal government at the discretion of the secretary of transportation. Historically, federal transportation funds have been distributed on the basis of an 80-20 split; that is, state and local governments must pony up 20 percent of funds for any project. That means states that have devoted little to public transit have been eligible for less federal money to address the historic lack of investment.

This has created a challenge for local officials who are trying to enhance public transit in states that traditionally have given it little support. For example, in Alabama, the only state that provides no state funding for public transportation, only 1 percent of the $168 million in infrastructure bill funding it received has gone to mass transit, according to the National League of Cities tracker. An Inside Climate News analysis of federal energy data last year showed Alabama has the highest per-capita gasoline consumption in the nation.

Under the new Build Green bill, no less than 30 percent of total grant funds would go to rural areas, and no less than 40 percent to disadvantaged communities and areas that currently experience high adverse health and environmental impacts from pollution. The legislation also would guarantee that each state receive at least $4 billion for eligible programs and that no state receive more than $40 billion.

The new bill also adds a slew of labor provisions that were not in the original legislation. Not only would projects have to meet the same Buy America standards as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, there would be new requirements related to prevailing and minimum wages, paid leave and fair scheduling, local hiring and anti-misclassification. (That means employers could not avoid paying minimum wage and overtime by misclassifying employees as independent contractors.)

Warren and Garcia have introduced the measure at a time when moving any new clean energy spending measure through Congress would be an uphill battle at best, with Republicans in control of the Hoe and Democrats facing a tough battle this year in holding on to the Senate. Just last week, at a Senate Budget Committee hearing on the oil industry and climate change, Republican members blasted previous clean energy spending bills while voicing disbelief in the science that fossil fuel emissions are driving catastrophic climate change.

“Why are we projecting spending trillions of dollars to impact something that we really in the end can’t change?” asked Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI).

But Levin said that despite such pronouncements, Congress will be spending more on transportation soon. A new surface transportation reauthorization is ahead in 2026, and spending from the infrastructure law runs out that year as well.

“Are we jt going to think of it as a reauthorization and not set ourselves up to meet the crisis of the day?” he asked. “These members of Congress, our organization and communities involved are saying, ‘We’re not going to show up the day before with a plan.’ We’re going to show up now, build support and get input from all kinds of folks. Transportation reauthorization should be a moment when we fund transportation at the scale communities actually need.”