When I first encountered 21-year-old Dilan Pinzón back in April, he was sitting on the sidelines of a soccer field in Oakland, California, clad in cleats and a blue jersey, pondering his team’s fate.

It was the third game of the season for Soccer Without Borders Academy, which hadn’t won a single match it played the previous season, the team’s first. Beyond the normal challenges of fielding a winning roster, Pinzón and most of his student teammates are recently arrived immigrants. Some, like him, are in the United States without family support, and have financial responsibilities—jobs on top of schoolwork—that make coordinating a full practice impossible. Traveling to workouts feels risky, too, with Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents randomly targeting people based on language and skin color. “We are not a normal team,” notes coach Eric Cortez.

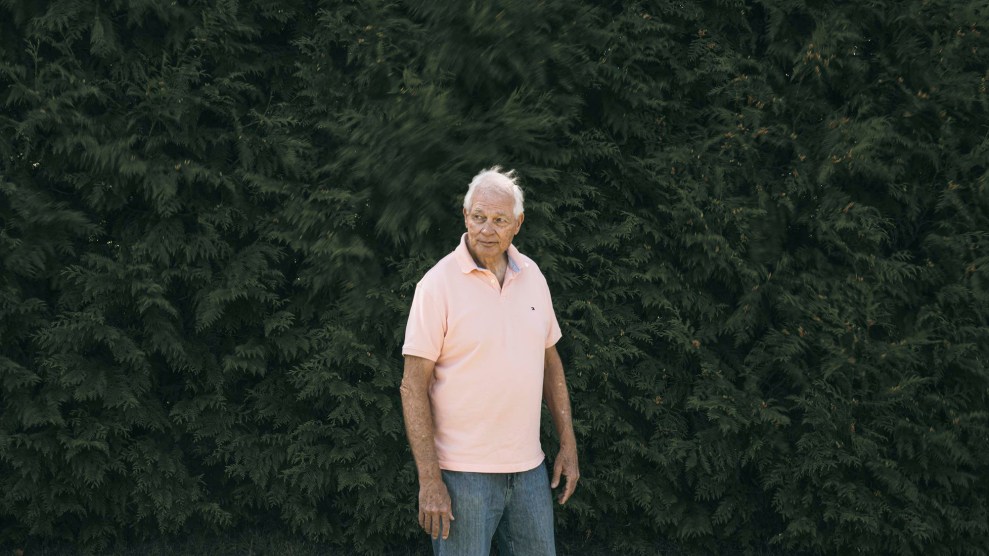

Pinzón, who has freckles across his nose and a Donald Duck tattoo on his calf, seemed restless as he waited to sub in, doing calisthenics to keep moving. He arrived in 2023 as a teenager, traveling from Colombia with his dad, who abandoned him soon after. For eight months, he slept alone in a Planet Fitness parking lot, in a rented Prius, before enrolling at Oakland International High School. The saga cost him years of schooling, and so he enrolled as a sophomore at age 19, supporting himself by making food deliveries, often until 3 a.m. But despite his sleep deprivation, Pinzón was never late to a game. Being on the field with this team, he told me in Spanish, is “my perfect place.”

Soccer Without Borders, the nonprofit that manages Pinzón’s team and similar ones for boys and girls around the Bay Area, was launched in 2005 to support newly arrived youth—Alameda County, home to Oakland, hosts one of the nation’s largest populations of unaccompanied immigrant minors. Early practices were held on a concrete pitch outside Oakland International. Today, the school has an astroturf field and SWB has expanded to Colorado, Maryland, and Massachusetts, managing 50-plus US teams and more internationally. Unlike most youth soccer clubs, its teams are free to join and can offer players, who hail from 74 countries, some semblance of safety, camaraderie, and even normalcy as they navigate President Donald Trump’s deportation crackdown.

Pinzón’s squad is SWB’s eldest, designed for players who are no longer eligible for the youth leagues but may still be in high school because of gaps in their education. His teammates hail from Chile, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru. Many have played competitively since they were little, but the squad’s debut season in the semipro United Premier Soccer League proved a rude awakening. They lost several matches by three or more goals—including one 9–0 drubbing—in part because their schedules made it so difficult to practice together. They had trouble gelling.

“We weren’t ready,” admits James Ullyse, a soft-spoken Haitian forward who juggled junior year coursework with shifts at Whole Foods Market and a nearby restaurant. “I was so frustrated,” recalls Joaquin Zapata Bueso, another forward, who came from Honduras at age 16 and worked as a waiter and an airport wheelchair assistant while finishing high school. “¡Tranquilo, tranquilo!” coach Cortez would yell from the sidelines to settle his players when their tempers flared on the field.

Still, the game provides a distraction from their demons. Pinzón and his father, who faced threats from gang members in Colombia, left home because of safety concerns. During their harrowing trek via Mexico, armed men kidnapped them, forced them to pay ransom, and left them in the desert. Pinzón eventually swam across the Rio Grande to Texas and presented himself to Border Patrol officers, who handcuffed him and sent him to detention for four days. After he and his dad were released to pursue their immigration cases, they used savings to fly to California. “I don’t have a good relationship with my dad,” Pinzón says. “Since I arrived here, I’ve literally been alone.” When they parted ways, he slept on the streets for two days before renting the Prius from an acquaintance.

The challenges faced by unaccompanied minors go well beyond room and board. Hiring an immigration lawyer is expensive, and free legal help is in short supply. So are bilingual therapists, notes Kristina Lovato, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who has interviewed unaccompanied minors about the “triple trauma” of escaping hardship at home and surviving migration only to end up in hostile environments. Havens like the SWB team can help, but “not being welcome,” Lovato says, “does a lot to one’s psychosocial development and psyche.”

Trump’s deportations have ratcheted up players’ anxiety: Some leave practice early or skip games to spend more time at home, where they feel safer. Pinzón no longer does food deliveries at night, having spotted cars occupied by ICE officers. “The truth is, I’m scared because I don’t want something to happen to me,” he says. “I’m afraid with some of the stuff I see on the news or social media.”

Amid this atmosphere, the team plays a support role, helping assuage fears. Players might share job leads or remind each other about court dates, but for the most part the field is simply a place they can feel like kids again, for a few hours at least. “The game becomes a medicine,” Cortez says. “There’s a built sense of belonging.”

Cortez, a US citizen who grew up in Mexico and California, is not only a coach, but also an SWB staffer who develops programming for the players. He helps them learn English, reviews résumés, and encourages them to apply to college. Some, especially the older ones here alone, can’t always afford three meals a day—last spring, Cortez had a nutritionist come to practice to help his players plan how to get enough vegetables, carbs, and protein.

Shortly after Pinzón signed up, he told a different SWB coach he’d been sleeping in a car, and the nonprofit helped him find a room of his own. He now shares an apartment with three teammates. In their limited free time, they’ll grab burgers after a match or play FIFA video games, says midfielder Carlos Cuadra, one of Pinzón’s housemates, who came from Nicaragua and joined the team along with his brother, Ricardo. “Honestly,” Pinzón told me, “we’re like a family.”

As the players got to know one another better, their game improved. Toward the end of the first season, they managed to come from behind in the second half to tie Stockton, one of the league’s top teams, before giving up a goal in the final seconds. It was another loss, but it felt like a turning point: We can compete.

When the second season began, the week after the Trump administration deported hundreds of migrants to a prison camp in El Salvador without due process, they were finally ready, winning their first two matches. I asked some players what had changed. “We’re the same, but we talk more,” says Ricardo Cuadra. “It’s the trust in ourselves and in each other.”

During one tight match in May, an opposing player shoved Cuadra in the face and a confrontation ensued until one of the older guys stepped in to calm him down. “You’re gonna get hit—just don’t react,” Cortez reminded his players at halftime. Minutes later, defender Danny Ayala Del Rio took a hard kick to the shin and collapsed in pain; the team carried him off the field with a fractured tibia and fibula. Midfielder Alan Ramos Guardado, from Guatemala, joined his teammate on the bench to rub ointment on his leg, and Cuadra, cooling off after a yellow card, affectionately gave Ayala Del Rio a smooch on the top of his head. (Ayala Del Rio spent the rest of the season on crutches.) In a postgame huddle later in the season, Pinzón praised Cuadra for moving the ball upfield. He then led a team cheer as everyone put their hands in: “Together on me, together on three!”

“If we win games, it’s all together. If we lose games, it’s all together,” Cortez told his players.

SWB finished its second season sixth out of 20 teams, missing the playoffs by a single goal. “Hopefully, we can make it” next season, Peruvian midfielder Maykel Martinez Relyz told me in Spanish. He’s one of several players who dream of going pro or who are considering coaching, remembering how lost they felt upon arrival and how much they now have to give back. “I had to go through a lot,” Pinzón told me.

As the border tightens and deportations expand, fewer immigrant teens will be arriving in Oakland—or anywhere in America. But for young athletes who make the journey, this squad is ready to help. “I’ve had a lot of joy on the team, and I’ve found my values,” says Zapata Bueso, the Honduran forward. “Any new players are welcome. We’ll receive them like family, too.”

Additional reporting by Steven Rascón.