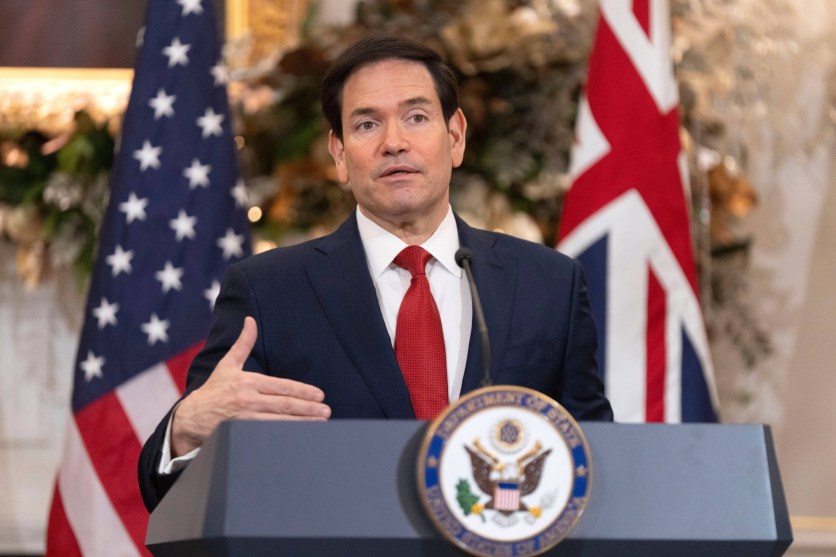

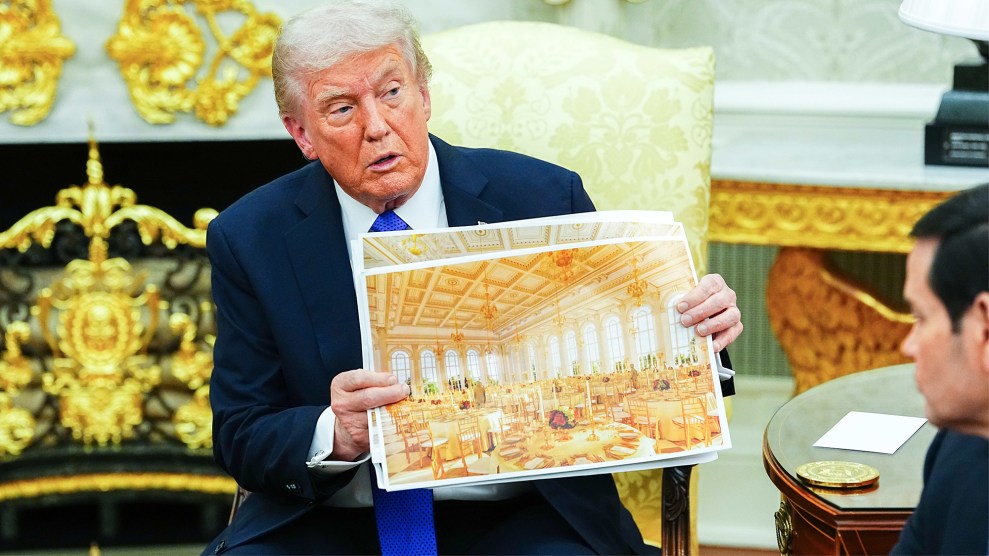

President Donald Trump shows an interior rendering of the new planned White House ballroom during an Oval Office meeting.Aaron Schwartz/CNP/Zuma

The second Trump administration has made tearing down parts of the federal government a priority. And some of those efforts have been literal. In October, President Donald Trump ordered the demolition of the White House’s East Wing to make way for the construction of a massive 90,000-square-foot ballroom. He’s also given the White House a gilded makeover, bulldozed the famed Rose Garden, and even has plans for a so-called “Arc de Trump” that mirrors France’s Arc de Triomphe.

So what’s behind all of this? Art historian Erin Thompson—author of Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America’s Public Monuments—says that whether it’s Romans repurposing idols of leaders who had fallen out of favor or the glorification of Civil War officers in the American South, monuments and public aesthetics aren’t just about the past. They’re about symbolizing power today.

“The aesthetic is a way to make the political physically present,” Thompson says. “It’s a way to make it seem like things are changing and like Trump is keeping his promises when he’s actually not.”On this week’s More To The Story, Thompson sits down with host Al Letson to discuss why Trump has decked out the White House in gold (so much gold), the rise and recent fall of Confederate monuments, and whether she thinks the Arc de Trump will ever get built.

Find More To The Story on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Pandora, or your favorite podcast app, and don’t forget to subscribe.

This following interview was edited for length and clarity. More To The Story transcripts are produced by a third-party transcription service and may contain errors.

Al Letson: What is an art crime professor?

Erin Thompson: Well, someone who’s gone to way too much school. I have a PhD in art history, and was finishing that up and thought, “Oh, I’m never going to get a job as an art historian. I should go to law school,” which I did, and ended up back in academia studying all of the intersections between art and crime. So I studied museum security, forgery, fraud, repatriations of stolen artwork. I could teach you how to steal a masterpiece, but then I would have to catch you.

So is it fair to say that The Thomas Crown Affair is one of your favorite movies?

No. Least favorite, opposite-

Really?

… because they make it seem like it’s a big deal to steal things from a museum, but it’s really, really easy to steal things from museums, as the Louvre heist just proved.

I was just about to say, I think the thieves at the Louvre would agree with you.

It’s hard to get away with stealing things from museums, which is why they got arrested immediately.

So how did you move from studying museum pieces and art crime into monuments?

Well, so my PhD is in ancient Greek and Roman arts, and when monuments began being protested in the summer of 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, people were commenting online, “Civilized people don’t take down monuments. This is horrible.” And I was thinking, “Well, studying the ancient world, everything that I study has been at one point torn down and thrown into a pit and then buried for thousands of years.” Actually, as humans, this is what we do. We make monuments and then we tear them down as soon as we decide we want to honor somebody else. So I thought I could maybe add some perspective. And then having my skills in researching fraud, I started to realize that so many of the most controversial monuments in the U.S. were essentially fundraising scams where a bunch of money was embezzled from people who wanted to support racism, essentially, by putting up giant monuments to white supremacy. So I thought, maybe that’s some interesting information for our current debates.

They got got, as they should.

Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

As somebody who grew up in the South, I would just say as a young Black man growing up in the shadow of these monuments, watching them go down felt like finally, finally this country was recognizing me in some small way. And I was completely unsurprised at the uproar from a lot of people who wanted to keep these monuments up. But when you dig into why these monuments were placed down, a lot of them were done just … Especially when we’re talking about Civil War monuments in the South and in other places, they were primarily put there to silence or to intimidate the Black population in a said area.

Yeah, I call them victory monuments. They’re not about the defeat of the Confederates, they’re about the victory of Jim Crow and other means of reclaiming political and economic power for the white population of the South.

Yeah. And so talk to me a little bit about the monuments themselves and how a lot of those were scams. I had never heard of that before.

So for example, just outside of Atlanta in Stone Mountain, Georgia is the world’s largest Confederate monument, a gigantic carving into the side of a cliff of Lee and Jackson and Jefferson Davis. And that was launched in 1914 by a sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, working with the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The Klan enthusiastically embraced the project. They stacked the board. They took a bunch of the donations. Essentially, no progress was made for years and years and years until the 1950s when as a sign of resistance to Brown v. Board, the state of Georgia took over the monument and finally finished it. So it wasn’t finished until the 1970s. And to me, the makers said it should be a shrine to the South. It’s more like a shrine to a scam.

The Klan leaders who led the project even fired Borglum at a certain point because they thought he was taking too much money. But he landed on his feet because he persuaded some Dakota businessmen to sponsor him to carve what turned into Mount Rushmore. So he defected from glorifying the Confederacy to carve a monument to the Union. So he didn’t really care about the glory of the Confederacy, he just wanted to make some money.

So in the United States, how have monuments historically been funded?

Well, the American government, both state and federal has always been a bit of a cheapskate when it comes to putting up public art. So most monuments that we see were actually privately fundraised, planned, and then donated to local governments. So they’re not really public art. They were put up by small groups for reasons. If you look, for example, at the Confederate monument that used to be in Birmingham, Alabama, this is a little weird that Birmingham had a Confederate monument in the first place because they were founded as a city well after the close of the Civil War. And the monument went up in two parts, both of which were in response to interracial unionization efforts. So the leaders, the owners and managers of the mines, when the miners were threatening to strike said, “No, no, no, no, no, no. We need to remind our white workers that they have to keep maintaining the segregation that their fathers or grandfathers fought for, so let’s put up this Civil War Monument.”

So monuments don’t tell you very detailed versions of history, but also even thinking about history is kind of leading you on the wrong track when you look at, well, who is actually paying for these monuments top people put up and what did they actually want from them?

So tell me, just pulling back a little bit, what’s the relationship between monuments and society?

Monuments are our visions of the future. We put up a monument when we want people to aspire to that condition. We put up monuments to honor people to inspire people to follow their examples. So that sounds good and cheerful, right? It’s nothing wrong with having models and aspirations, but you have to think about, well, monuments are expensive. So who has the money to pay for them? Who has the political power to put them in place permanently? And you’ll often see that monuments are used to try and shape a community into a different form than it currently has. I live in New York City, for example, and almost all of the monuments put up until the last few decades are of white men. And what kind of message does that send to this incredibly diverse community of who deserves honor?

And you said earlier that throughout time we have erected monuments and taken them down. Can you talk that cycle through with me?

Yeah. Well, take the Romans, for example. Roman emperors would win a victory at war and put up a big victory monument, a triumphal arch or portraits of themselves. And then after the emperor died, the Senate would vote and decide, was this a good one or a bad one? Do we want to decide officially that they have become a deity and are to be honored forever, or do we want to forget their memory? And it was about a third, a third, a third. A third was no vote, a third were deities, a third were their memories were subjected to what we call damnatio memoriae. And if that happened to you, they would chisel the face off your statues and carve on your successor. The Romans were thrifty that way. They reused sculptures-

Wow. So they recycled.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Wow.

Or they would break things up or melt it down and make it into a new statue. So this was a pretty common strategy of, just like we do it in a much more peaceable form, when a new president is elected, you take down the photo of the current president from the post office and put up the successor, etc, etc. So in the ancient world they had a more intense version of this, but you can think about the tearing down of statues of Saddam after his fall or the removal of statues of Lenin across the Soviet satellite states. This is something that we do when there are changes in power, and usually we don’t notice it because it’s more peaceful. There’s an official removal of the signs of the previous regime and a substitution with the others.

So what was special and different about the summer of 2020 was the change came from below. It was unofficial. We mostly saw people not tearing down monuments with their bare hands, that’s obviously hard to do, but modifying monuments by adding paints, signage, projections, etc.

And that’s exactly like what you looked at in Smashing Statues is the shift that, to me, in a lot of ways had been a long time coming. There had been movements here and there that were kind of under the radar for most people. But then after George Floyd, it’s like it got an injection of adrenaline, and suddenly all over the country you start seeing this stuff happening.

Yeah, and I think people lost patience. What wasn’t obvious to a lot of observers was that changing a monument or even questioning a monument is illegal in most of the U.S., or there’s just no process to do so. So I interviewed for the book Mike Forcia, an indigenous activist in Minnesota, and he had been trying for his entire adult life to get the state legislator to ask why is there a statue of Columbus in one of the cities with the largest concentrations of an urban indigenous population in the world? And all of his petitions were just thrown away. So he eventually had to commit civil disobedience, I would describe it, by pulling down the statue. There’s no other way to have that conversation.

Let me ask you, just to go back a little bit, how do these monuments shape and perceive history? Because you saying that this is what we’ve always done and the Romans would switch out faces and statues, that’s totally new to me. And so as somebody who grew up with Confederate statues around or Confederate names always around, I think it’s shaped the way I view the world. And also as they were coming down, not knowing that in the long arc of history that this is what we always do, it challenged the perceptions, I think of a lot of people.

Monuments are inherently simple. You can’t tell a full historical story in a couple figures in bronze. So I think they communicate very simple messages of this is the type of person that we honor. And they speak directly to our lizard brain, the part of us that sees something, “Oh, something big and shiny and higher than me is something worthy of respect.” So you can’t tell them a nuanced story in a monument, and that is used as a strength. I also think it’s a strength that they become boring. They fade into the background of our lived landscape, and then we don’t question their messages if we just think of the monument as something, oh, we’re going to tell each other, “Meet at the foot of this guy for our ultimate Frisbee game,” or something. So it is these moments of disruption that let us think, “This is supposed to stand for who we are as a people. Do we really want that guy up on the horse telling us who we are?”

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and these statues and monuments are coming down or they’re being defaced, my little sister lives in Richmond, Virginia and I went to visit her. And I’ve been to Richmond several times. And I think I’d seen pictures of the monuments in Richmond being graffiti on them, but I had not seen them in real life up close. And it was kind of stunning to me. Also, what was stunning about it, because in Richmond, if you’ve never been to Richmond, Richmond has like this … I don’t know what street it is, but this long row-

Monument Avenue.

Monument Avenue, thank you. Has Monument Avenue with all of these different monuments. After George Floyd, they were spray painted, and people were gathering around these monuments in a way that I’d never seen before.

I think those monuments went up to create a certain type of community. Monument Avenue was designed as a wealthy neighborhood, and how do you prevent the quote, unquote, “wrong type of people” from moving into your nice neighborhood? Well, put up some nice monuments celebrating Civil War generals. So it’s not-

You tell them they’re not welcome.

Yeah, exactly. So it’s a community created by exclusion, is what these monuments were put up for. And we actually see that again and again. In Charlottesville as well, the sculpture of Robert E. Lee that was recently melted down was put up to mark the exclusion of people from a neighborhood that had formerly been a neighborhood of Black housing and businesses, which they were condemned by eminent domain and turned into a cultural and park space that was intended to be whites only in the 1920s. So monuments are a powerful course for creating community. But you’re absolutely right that the removal can be a powerful force for creating community as well. And what saddens me is if you go to Richmond today, some of the bases of those monuments are still there. The Civil War monuments have been removed from Monument Avenue, but all of the graffiti has been scrubbed off. There’s no more people gathering there. It looks just like a traffic median again. And that’s true of almost everywhere in the U.S. The authorities are always a bit nervous about this type of spontaneous use of public space, I would say.

Yeah. Listeners to this podcast have heard me say this 101 times because it’s my thing, but I just believe that America is a pendulum, that it swings hard one way and then it comes right back and swings the other way. Which means that in the long-term, America sees progress in inches, but the swings are where you can see exactly where the country is right now. And so I think if we look at what happened after George Floyd died, that was a hard swing the other way. I’m curious if what we see right now coming from the Trump administration, and not just like in military, he’s reverting the names or changing the names of military bases back to people whose names have been taken off these military bases, all of that type of stuff, but also he’s planning to put an Arc de Trump in D.C., the East Wing Ballroom, all of that stuff, do you feel like that is the opposite swing of what we saw during George Floyd’s death?

Oh, yeah. And even literally, recently the Trump administration said that they were going to reverse removal of statues. So they re-erected a Confederate general statute in D.C., and they’ve said that they’re going to put up the Arlington Confederate Monument, which would cost millions and millions and millions of dollars to put up. So we will see if that actually happens. But just declaring that you’re going to do it is enough of a propaganda victory, I think, in this situation.

Right.

It might seem silly or not worthy of attention to look into the Trump administration’s aesthetic decisions, all of the gold ornamentations smeared all over the Oval Office and ballrooms and Arc de Trumps, and etc, but the aesthetic is a way to make the political physically present. It’s a way to rally people’s energies. It’s a way to make it seem like things are changing and like Trump is keeping his promises when he’s actually not. I think he hasn’t really changed Washington in the way that he’s told his base he’s going to change. The elite are still in control of political power and wealth, but he is literally changing the White House by tearing part of it down. And you can channel people’s attention into rooting for that type of change instead of actual change.

And the style choices that he’s making are very congruent with his political message, in that he’s appealing to a vision of the past, which is greater than the present. But in both his political message and his aesthetic style, this vision of the past, you can’t pinpoint it. It’s not an actual time. It’s a fuzzy, hand-wavy, things were prettier and nicer than. And so you can’t fact-check that type of vision. You can’t see if we’ve actually gotten closer to it. And so putting up a gilded tchotchke counts as progress towards that, and he can claim the credit, which he’s happy to do.

Yeah. And I think that’s intentional, because if you can’t land on the specific time period, you can’t be held accountable for how that time period played out for the disenfranchised.

Or for the powerful of that time period.

Right. Right, exactly.

Appealing to making the White House look like Versailles. We all know what happened to the French kings, but apparently we’re not paying much attention. And there’s another current right tendency to appeal to the glory of Caesar. Everybody wants to be like Julius Caesar when that’s really not a good life choice, if you want to end up like him.

I think the other thing when I think about Trump’s aesthetic, so I grew up in the South but I am originally from New Jersey, and I remember Trump when I was really young, primarily because my dad was from Pleasantville, New Jersey, which is right outside of Atlantic City. And so there were conversations that I didn’t understand as a kid, and Trump was a part of those because he had his casinos and all of that type of stuff. And I just remember being a little kid and seeing a commercial for, I guess either it was Trump’s properties or it was a casino or whatever. And I just remember looking at it on the TV and seeing gold everywhere. That was his thing, gold. And the older I get, the more I realize that the way Trump sees gold and all the fittings that he has around, really is like him surrounding himself what he perceives of as wealth, and what people who don’t have wealth perceive of as wealth.

But the actual uber-rich, usually from what I’ve seen, do not decorate their houses in all gold, do not flaunt. Their wealth is present but quiet, whereas Trump’s wealth is present but loud. And that speaks to a lot of people who do not have the wealth. And in a sense, him putting gold around the White House is a secret, in my opinion, aspirational message to poor folks who do not have that, “One day you can have.” I don’t know, it’s just like a theory that I’ve been cooking in my head since I was a little kid.

I think absolutely. We have the proverb, “All that glitters is not gold” because people keep needing to be reminded. And yeah, again, in our primitive lizard brains, we think shiny equals good and I want that, and we don’t look below the surface. And I think that Trump’s focus on glitzing up the White House, on making these new constructions now in his second term is not accidental, because you often see populist leaders focusing on aesthetic projects towards the end of their political life. In Hitler’s last days in the bunker, he was still pouring over models for a museum that he was building in his hometown of Linz, in which he was planning to put all of the masterpieces seized from victims of the Holocaust from other museums across Europe. It was going to have 22 miles of galleries, all stuffed full of the artistic wealth of the world.

And I think there’s a comfort in this idea. Like, if I make something spectacular and beautiful enough, all of the cruelty that went into making it will be justified. I will be forgiven. So when I’m feeling depressed about the world, I think maybe this focus on the gold now is such an obsession because he recognizes that he’s on his way out.

What does it mean to a society that some of the tech leaders are now turning their attention towards building statues? You were just talking about how leaders when they’re beginning their twilight are … I guess they’re thinking about their legacy, and so they’re putting up these monuments and doing other things. But what does it mean for us when we have these tech bros that are doing it now?

Well, we’ve always seen this. Think about the Pantheon in Rome, that big circular temple. Across the front of it, you can still see the shapes of the letters that it used to have that was erected not by an emperor, but by a wealthy Roman who was doing so in service of the imperial cause. So big donors making big, splashy public projects have always been realizing that this is a good way to get in with the regime to shape things, to get loyalty from the public to their point of view as well. So today you look at people’s reactions to Elon Musk is very similar, I think to what you were talking about, the idea of, “I can also have this splashy level of wealth maybe someday, so I will follow somebody who I could see as a model of getting wealth, rather than someone who is actually going to do anything that’s actually good for me.”

Do you think that the Arc de Trump will ever be built?

That’s the thing about these Trumpian aesthetic actions, you can just put out the promise, you can release a picture of the renderings and claim victory, even though you haven’t actually done anything. I very much doubt that this arch is going to go up for a huge variety of reasons, but if it would go up, I don’t understand how it can be justified to spend that much money. When on the one hand you’re saying we are trying to cut government expenditure, there’s no justification for having tens of millions probably going on an arch to yourself.