I guess today is David Dayen day. Over at the New Republic, he points me to an interesting new historical study of systemic banking crises. Here’s what happens when the financial system implodes:

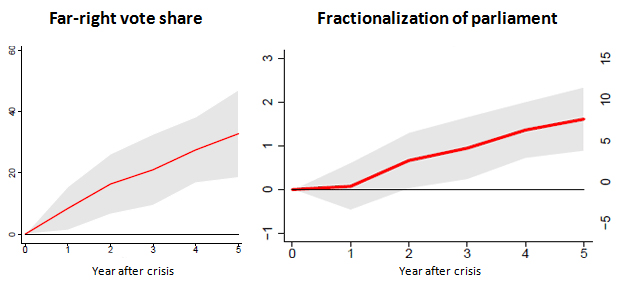

Both before and after WWII, the authors find the same dynamic: the voting share of far-right parties increases by about a third and national legislatures become more fractured and dysfunctional. This doesn’t happen after normal recessions. Only after major recessions caused by a banking crisis.

Why? The authors are unsure. One possible explanation, they say, is that financial crises “may have social repercussions that are not observable after non-financial recessions. For example, it is possible that the disputes between creditors and debtors are uglier or that inequality rises more strongly….Financial crises typically involve bailouts for the financial sector and these are highly unpopular, which may result in greater political dissatisfaction.” Or maybe this: “After a crisis, voters seem to be particularly attracted to the political rhetoric of the extreme right, which often attributes blame to minorities or foreigners.”

Since we’re guessing here, I’ll add my two cents. People are, in general, more generous when times are good. Policywise, they’re more likely to approve of safety net programs that help the poor, which are generally associated with the left. But when times turn bad, people get scared and mean—and the longer the bad times last, the meaner they get. When people have lost their jobs, or had their hours cut, or seen the value of their home crash, they’re just not as sympathetic to helping out the poor. They’re looking out for their own families instead.

Politically, the result of this is pretty obvious. Liberal parties think that bad times are precisely when the poor need the most help, so they propose more social spending. Right-wing parties, by contrast, oppose increased spending.

In public, this usually isn’t framed as support or opposition to doling out money to the poor. Liberals talk about stimulus and countercyclical spending. Conservatives talk about massive budget deficits and skyrocketing government outlays.  But it doesn’t really matter. What people hear is that liberals want to spend more on the poor and conservatives don’t. When people are feeling vulnerable and mean, the conservative message resonates with them.

But it doesn’t really matter. What people hear is that liberals want to spend more on the poor and conservatives don’t. When people are feeling vulnerable and mean, the conservative message resonates with them.

From a practical policy standpoint, this makes little sense. Liberals are right that recessions are the best time to spend more on safety-net programs, both because the poor need the help and because it acts as useful stimulus. But human nature doesn’t work that way, and conservatives have the better read on that.

So what’s the answer? Dayen suggests that banks and bank bailouts are central to this dynamic, so we need to take a meat axe to the political power of the financial sector. I’m all for that. But my guess is that this isn’t really key. I think people just get scared when times are bad, and hate the idea of their tax dollars going to other people. This means the answer is to assuage both their financial anxiety and their perception that their money is being spent on the poor. So how about something that dramatically makes this point? Say, a one-year income tax holiday for everyone making less than $70,000 coupled with explicit promises to increase the deficit and help the poor. The tax holiday could be extended year by year as necessary, or phased out gradually.

Why something like this? Because it puts more money in everyone’s pocket and reduces their angst over money matters. It also makes it crystal clear that their money isn’t being spent on the poor. They aren’t paying any taxes, after all. Under those circumstances, helping out the poor would probably strike most people as a lovely idea.

Obviously conservatives would still oppose this, and the tax holiday wouldn’t last forever. Still, it’s worth a thought. You need something dramatic to cut through people’s fears, and this might do it.

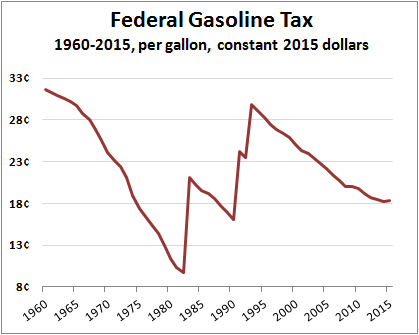

money from a Federal Reserve surplus account that works as a sort of cushion to help the bank pay for potential losses.

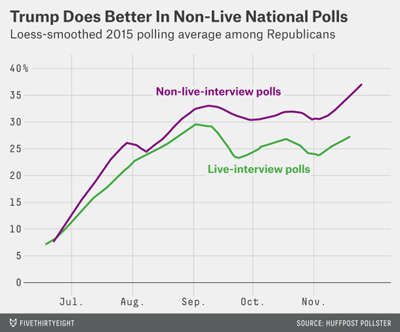

money from a Federal Reserve surplus account that works as a sort of cushion to help the bank pay for potential losses. Here’s something pretty interesting: It turns out that Donald Trump does significantly better in robocall and online polls than he does in traditional live-interview polls.

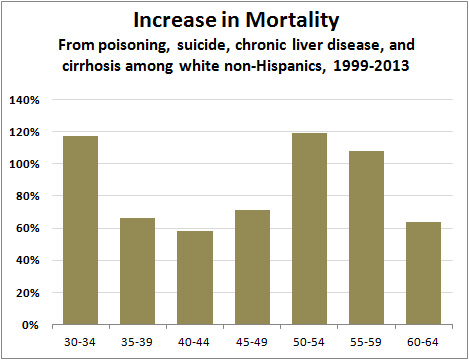

Here’s something pretty interesting: It turns out that Donald Trump does significantly better in robocall and online polls than he does in traditional live-interview polls.  or the slow motion suicide of chronic substance abuse.

or the slow motion suicide of chronic substance abuse. I don’t think I’d bother with this if I had something better to write about, but when life hands you lemons, you write a blog post with them anyway.

I don’t think I’d bother with this if I had something better to write about, but when life hands you lemons, you write a blog post with them anyway.  everyone is still trying to figure how to price their plans. The key element is that companies that make less than a certain amount will be compensated.

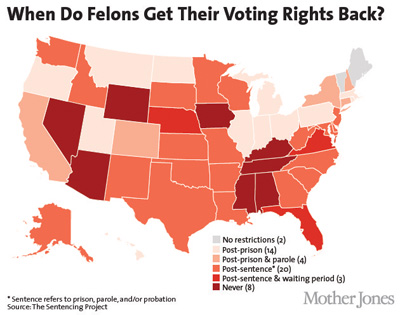

everyone is still trying to figure how to price their plans. The key element is that companies that make less than a certain amount will be compensated.  not to vote for Democrats, either. They just don’t vote.

not to vote for Democrats, either. They just don’t vote.