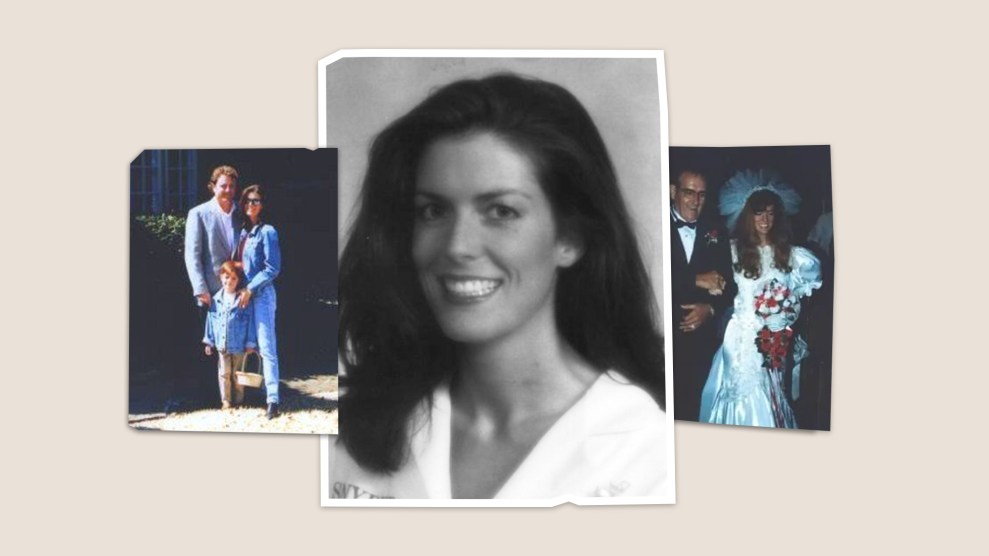

Mother Jones illustration; Photos courtesy of April Wilkens

Oklahoma incarcerates more women per capita than nearly any other state, and many of them are survivors of domestic violence.

Last year, I wrote about April Wilkens, who’s serving a life sentence in McLoud, Oklahoma, for killing her ex-fiancé, Terry Carlton, in 1998. Carlton, the wealthy son of a car dealership owner, repeatedly abused Wilkens during their relationship, according to court records. She shot him eight times one night after he allegedly held a gun to her head, raped her, and then handcuffed her at his house; she said it was self-defense, and a medical exam documented vaginal abrasions and tears. But a prosecutor claimed she was “cry[ing] rape,” and a jury convicted her of first-degree murder.

As I reported last year, Wilkens eventually became eligible for parole but was struggling to convince Oklahoma’s parole board to release her from Mabel Bassett Correctional Center, even though she’d stayed out of trouble in prison. She suspected they kept rejecting her bids for freedom because Carlton’s family wanted her to remain incarcerated.

Then came some hopeful news. In February, Republican state Rep. Toni Hasenbeck wrote the Domestic Abuse Survivorship Act, a bill that would let judges retroactively resentence incarcerated survivors like Wilkens. More specifically, the bill would cap prison terms at 10 years for prisoners who committed a crime against their abusive romantic partner in a situation where they could have at least claimed self-defense. The bill would also apply to future cases.

Not many states have laws that allow survivors to retroactively seek shortened sentences—and those that do, such as New York, California, and Illinois, are more liberal than Oklahoma. So I was initially surprised last week to read that Oklahoma’s House unanimously passed the bill, sending it on to the state Senate. “This is a momentous day for domestic abuse survivors in Oklahoma,” Alexandra Bailey, a campaign strategist at the Sentencing Project, a national criminal justice reform group, wrote in a statement after the vote. “Rigid and extreme sentencing laws have devastated far too many women and children in the Sooner State.”

But there was a big catch: To make the bill more palatable to other Republicans, Rep. Hasenbeck watered it down—significantly—before the House vote. Instead of limiting prison terms, the new bill simply requires courts to consider a person’s history of abuse as a mitigating factor, and it gives judges the option “to depart from the applicable sentence” and offer a shorter prison term. In the end, however, judges would still have the power to punish as they see fit.

And crucially, the amended legislation would no longer apply retroactively—doing nothing for Wilkens and other survivors who are currently in prison. “To allow prospective relief while sacrificing survivors who have already been sentenced to prison is a half measure,” Colleen McCarty, an attorney at the Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, a justice reform group, wrote in a statement after the House vote, “one intended to help us all feel good about our progress at the expense of our forgotten daughters.”(McCarty recently helped launch the podcast Panic Button to spread the word about Wilkens’ case.)

The bill will also leave out other types of survivors who commit crimes that stem from their domestic abuse. Unlike New York’s Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act, which passed in 2019, Oklahoma’s bill would not assist survivors who, for example, are convicted for taking illicit drugs to cope with their abuse, or selling drugs at their abusers’ demand, or stealing money or food while trying to escape. And that’s likely a lot of people. While good national data is hard to come by, a study in New York found that 94 percent of incarcerated women had experienced physical or sexual violence before landing behind bars, and the vast majority of them were victims of intimate partner violence. In Oklahoma, McCarty estimates that anywhere from 100 to 500 Oklahoma women are now locked up for crimes stemming from domestic abuse. Some of them were convicted under the state’s controversial “failure to protect” law, the subject of a recent Mother Jones investigation. The law criminalizes parents who do not protect their children from another adult’s harm, but it often punishes mothers who simply could not fight back against their violent boyfriends.

Given the Oklahoma House’s unanimous support for the Domestic Abuse Survivorship Act, McCarty and other activists are now trying to convince state Senators to revert back to the original language allowing for retroactive resentencing, to help Wilkens and others like her. It’s unclear what success they might have: The Oklahoma District Attorneys Council, a powerful lobbying group of local prosecutors, reportedly opposes retroactive relief. (The DA Council did not respond to my requests for comment, and Rep. Hasenbeck agreed to an interview but did not answer my calls.)

At the very least, survivor advocates I spoke with hope Oklahoma senators don’t water down the bill even more. “It’s a narrower impact,” Tracey Lyall, who leads the nonprofit Domestic Violence Intervention Services in Tulsa, says of the amended bill, “but it will still have an impact on some survivors.”