Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/billypalooza/3184530981/sizes/m/in/photostream/">billypalooza</a> (<a href="http://www.creativecommons.org">Creative Commons</a>).

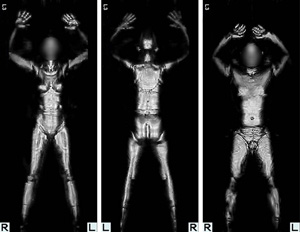

In late October, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which handles airport security in the US, began offering passengers a choice: either submit to being imaged by the new, invasive, “backscatter” scanners, which show your genitals to the security officers manning the machine, or risk having your junk touched by those same officers. New regulations require that the TSA perform “enhanced pat-downs”—which some critics have described as “groping”—of anyone who declines the controversial full-body scan. If you decline both procedures, as Californian John Tyner did this week, you can be investigated and face fines up to $11,000.

Although a recent poll showed that over 80 percent of Americans are okay with the new scanners, the forced choice between the “naked” imaging and the new pat-downs has a vocal group of fliers and airport security reformers up in arms. On October 29, Atlantic magazine writer Jeff Goldberg, who’s cultivated a sort of side-career as an airport security reformer, wrote a hilarious blog post about his experience with the new pat-downs. The post, in which Goldberg banters with TSA officers about his testicles, was widely circulated on the Internet. But it wasn’t until John “Don’t Touch My Junk” Tyner taped his own encounter with the TSA that the story really took off, fuelling criticism of the TSA across the media and political spectrum.

My colleague Kevin Drum is tired of hearing the complaints. So on Monday, he issued a challenge:

[W]hat I haven’t seen is an informed take on what airport security ought to look like. We all hate taking off our shoes and pulling out our laptops and being limited to three ounces of liquid and not being allowed to meet people at the gate anymore — we hate all of that. But if it’s all useless, what should we do instead? Shouldn’t someone write that article?

Ever dutiful, I set out to complete Kevin’s assignment. I asked Goldberg, security expert Bruce Schneier, and airline pilot (and security critic) Patrick Smith about what their ideal airport security schemes would look like. After speaking to them, I think Kevin is missing the point: the elimination of existing useless security procedures is the heart of the plan. It’s not about doing something “instead” of the current system—it’s about not doing things that are wasting money and time and not making us safer. It’s quite possible that we’re already as safe as we’re going to get—and every subsequent airport security “improvement” is just reducing our freedom without improving security.

Schneier is famous for explaining that “exactly two things have made us safer since 9/11: reinforcing the cockpit door and convincing passengers they need to fight back. Everything else is a waste of money.” All three experts favor scrapping most of the security measures that people hate—and not necessarily replacing them with anything. Ideally, the money that was saved wouldn’t be spent on airport security at all: it would be spent on trying to stop terrorists before they got to the airport. That means better-funding law enforcement and intelligence.

All that said, Goldberg, Schneier, and Smith did offer some suggestions for new or different security procedures to use “instead” of the methods we’re currently relying on. Here are a few options:

- Enhance baggage security. All three experts mentioned this. Baggage is where the greatest danger is, and where airport security resources should be focused. “Right now the biggest threats are still bombs and explosives. That’s the path of least resistance,” Smith says. “All luggage going on passenger planes should be treated the same, and scanned,” says Schneier. Making sure that a passenger’s bags never, ever fly if he doesn’t is also key. And we could do more. Here’s an excerpt from a 2006 article by Schneier:

If I were investing in security, I would fund significant research into computer-assisted screening equipment for both checked and carry-on bags, but wouldn’t spend a lot of money on invasive screening procedures and secondary screening. I would much rather have well-trained security personnel wandering around the airport, both in and out of uniform, looking for suspicious actions.

- Pay more attention to airport workers. Schneier was an early advocate of background checks and increased screening for airport employees. If you’re screening pilots, it’s “completely absurd” not to screen the guy who is loading food on the plane, Smith says. This has improved in recent years, and the TSA now conducts random screening of airport employees. That could be broadened. Goldberg suggested considering biometric IDs for airport employees.

- Randomize enhanced screening. Schneier has suggested that any “enhanced” screening of passengers be “truly random.” That means that while the majority of passengers wouldn’t face the invasive security checks they face now, every passenger would face the risk of a thorough search. Terrorists can’t avoid or plan for truly random enhanced searches, like they can with protocol-, background-, and profiling-based searches. You don’t want terrorists to be able to plan their way around your security. You want them to have to get lucky.

- Make security lines less vulnerable. The huge lines of people waiting in airport security lines are themselves a huge target. “If you want to terrorize the country, you don’t have to take down an airplane, you can just take people down in a security line,” Goldberg says. “All these people packed in tightly waiting and waiting and waiting… The next day all the airports in America will be closed.” Moving people through security quickly and efficiently will make the security lines themselves less of a target.

- The Israeli model is unworkable on a large scale. But that doesn’t mean you can’t replicate parts of it. Some people believe that America should move to the Israeli model of airport security: intense screening based on asking passengers many, many questions and assessing their responses. But the experts I spoke to don’t think that plan is workable in the United States. Israel has one medium-sized airport, and it would be next to impossible (and incredibly expensive) to enact Israeli-style security procedures in a country the size of the US. But that doesn’t mean you couldn’t have more (well-trained!) people observing passengers’ behavior or asking key questions of randomly selected passengers.