<a target="_blank" href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/duncan/6540449921/sizes/m/in/photostream/">Flickr/Duncan</a>

Tarek Mehanna, the Boston native who was accused of material support for terrorism based on what prosecutors said was his online advocacy on behalf of al Qaeda, was found guilty on all counts Monday.

Defense lawyers argued that Mehanna did not provide support to Al Qaeda. They said he was simply expressing his own views in opposition to US foreign policy, particularly to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, activity that was protected by the First Amendment.

They also called Mehanna a budding young scholar committed to his religion, saying he had traveled to Yemen in search of education — to further his studies on Islamic law and on Arabic.

But a series of Mehanna’s former friends testified against him that he had promoted extreme ideology, endorsed the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, and once called Osama bin Laden his father. Together, the former friends said, they watched videos glorifying suicide bombings in Iraq.

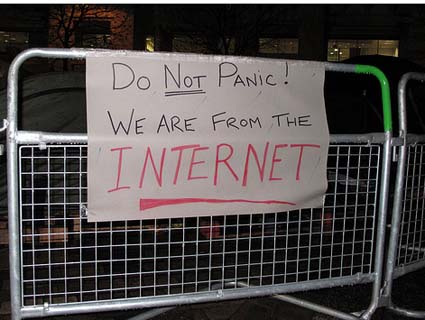

The verdict could turn out to be significant because Mehanna was not only accused of lying to prosecutors and seeking terrorist training in Yemen—prosecutors also charged that his translating of Al Qaeda documents and posting of extremist Internet videos was meant to sway Westerners to Al Qaeda’s cause, and therefore constituted material support for terrorism.

In the indictment, the authorities alleged that Mehanna responded to specific requests from individuals associated with Al Qaeda to translate and post materials. Prosecutors don’t seem to have raised that allegation at trial. Instead, they focused on the argument that Mehanna was responding to a general call made by Al Qaeda to spread their ideology. The distinction is important because, as I reported in my piece last week, the Supreme Court recently ruled that even nonviolent activities, if performed at the direction or under the control of a terrorist organization, could be crimes. Before, speech could only be a crime if it is both meant to and could credibly lead to “imminent lawless action.”

My personal view is that the prosecution’s other charges were strong already and Mehanna was likely guilty of those. However, by convicting Mehanna of material support for terrorism based on his online activities, the prosecution may have established a path through which the government can throw people in prison on terrorism charges for expressing abhorrent opinions, even if the individual in question has no direct ties to a terrorist organization.

For government authorities increasingly worried about the growth of the English-speaking extremist community and the possibility of homegrown terror, the Mehanna conviction may provide what is, in their view, a salutory chilling effect. For civil libertarians concerned about the government being able to prosecute ugly speech as a crime, that chilling effect is anything but salutory, because it could end up curtailing the rights of other critics of the US government, not just those who commit crimes based on their beliefs. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that at some level the US government is now in the business of policing which views are appropriate to express.