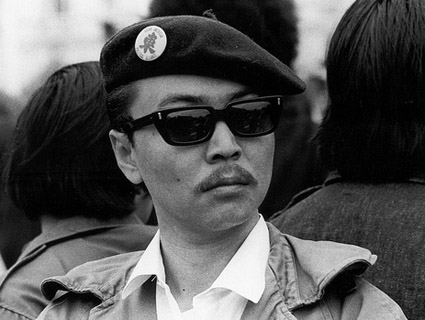

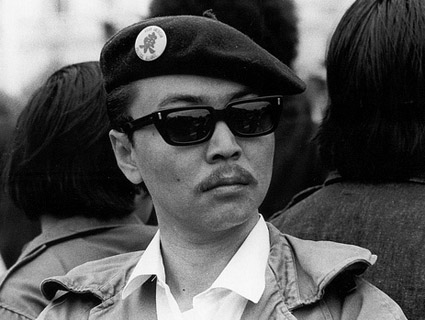

Richard Aoki<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/californiawatch/7797966838/in/photostream/">California Watch</a>/Flickr

When the Center for Investigative Reporting published a bombshell report last month that the late Black Panther Richard Aoki was an FBI informant, the news was met with disbelief. The longtime Bay Area radical’s friends and defenders argued that the evidence fell short, pointing to an ambiguous FBI document and a misinterpreted interview with Aoki. And why, they wondered, had there never been any hint of Aoki’s betrayal during his years of work uniting Asian-American and African-American activists?

But last week CIR reporter Seth Rosenfeld published another 221 pages of FBI documents that show conclusively Aoki was an informant. They reveal that Aoki, who used the alias “Richard Ford,” worked with the agency from 1961 to 1977, during which time he helped organize and arm the Black Panthers while providing the feds with information that was “unique” and of “extreme value.”

On Sunday, former Black Panthers and other local activists met at Oakland’s Eastside Cultural Center to discuss the revelations about Aoki. The event, titled “Cointelpro Attacks & Reclaiming the Legacy,” didn’t focus on the specific charges in Rosenfeld’s reports, according to people who attended the meeting, but most speakers were unwilling to accept that Aoki ever worked with the FBI.

At the meeting, Black Panther Party cofounder Bobby Seale said the charges against Aoki amounted to an attempt to defame a comrade. When Rosenfeld called him for an interview for one of his stories, Seale said, he replied, “Fuck it.”

Others suspect the FBI of “snitch-jacketing,” falsely accusing Aoki of working with the feds to sow doubt and suspicions among his fellow organizers. But no one has backed up these allegations, and it’s unclear exactly why FBI would choose to undermine Aoki’s reputation more than three years after his death. Nor does this theory explain why the FBI fought Rosenfeld over the release of the Aoki documents.

“I think people are skeptical for the right reasons,” Scott Johnson, an activist who attended the meeting, told me. “They’re trying to rescue as much [of his legacy] as possible while grappling with these new allegations.”

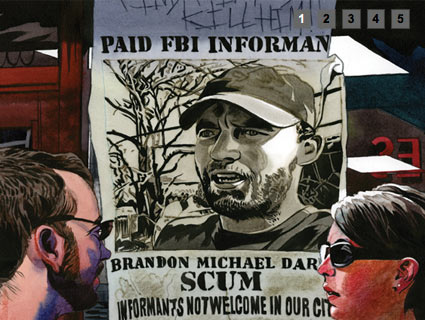

Skepticism in the face of betrayal isn’t unique to the Aoki situation. As MoJo‘s Josh Harkinson reported in his profile of informant Brandon Darby, his friends initially couldn’t believe the news that he’d snitched on his fellow Republican National Convention protesters in 2008. “If Brandon was conning me, and many others, it would be the biggest lie of my life since I found out the truth about Santa Claus,” wrote one of the many activists who were quick to defend Darby before he fessed up.

Of course, Aoki no longer has the opportunity to confess, and some of his defenders may never be swayed. Fred Ho, a writer and activist who befriended Aoki in the late ’90s, wrote an impassioned defense of his friend after reading Rosenfeld’s initial report. “If Aoki was an agent, so what?” he wrote derisively. “He surely was a piss-poor one because what he contributed to the movement is enormously greater than anything he could have detracted or derailed.” After last week’s follow-up story, Ho held firm, going so far as to suggest that Aoki may have been spying not on Black Panthers but on the FBI.

If Aoki were still alive, would his friends be rushing to his defense? He appears to have feared that they wouldn’t have. The FBI’s final report on Aoki reveals that he ended his relationship with the bureau since he felt that being an informant conflicted with his job as an educator. He was unwilling to reveal his past with the agency, the report says, because it “would alienate him from associates and friends and would cause him great trouble in his relationships with students as a student counselor.” It is unlikely, the report concludes, that “there will be any control problem concerning this informant.”