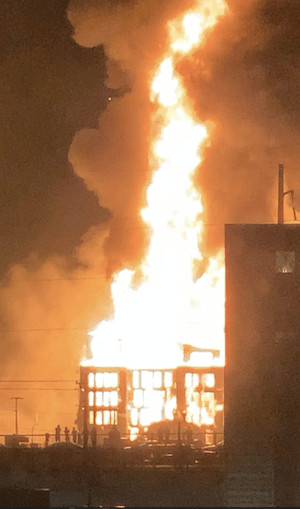

Courtesy of Norah Long

For the last four nights, protests and riots have ripped across Minneapolis in an explosion of pain and fury over the alleged murder of George Floyd, a black man, at the hands of white former Minneapolis Police officer Derek Chauvin. Early on Friday morning, people overran and torched the police department’s Third Precinct on Lake Street, in a diverse yet gentrifying South Minneapolis neighborhood near the nightclub where Chauvin and Floyd both worked security. Nearby buildings were looted or lit on fire, including corporate businesses like Target, as well as a Native American youth center and an under-construction affordable housing development.

Norah Long, a 51-year-old performing artist, lives in a condo above a grocery store a couple of blocks from the Third Precinct. I spoke with Long by phone on Friday afternoon, after a power outage, as she stood at a window watching the rising smoke and the National Guard down below. What follows is a condensed and edited transcript of her comments.

Today is not a typical day on Lake Street. Most days on Lake Street, you do not see people walking around with their cameras out, taking pictures like they’re at Disneyland. Everybody’s checking out, frankly, the destruction. It’s calm. It’s peaceful. It’s almost like they’re inside a museum. But they’re not in a museum.

The first day this started, the police were a strong force at the precinct. They were up on the roof, taking a stand. We were listening to a police scanner, and hearing them talk about, “Push that crowd back 50 feet to the west.” We were west. Things started moving this way. You could see it, literally store by store, move and move and move until we were right in the middle of it. Lots of glass breaking. Lots of explosions. Tires squealing. Running, yelling, shouting.

I know, in my heart, that the people, these crowds of protesters and rioters were not out here to harm people. That wasn’t the objective. But most people don’t know that there are three levels of condos in this building. They think it’s a corporate building. They don’t look up.

People were coming over in these waves. They’d gotten Pineda Tacos, which is this little family owned business. They got Subway, Dollar General. We were the next place. One of my neighbors is tall, imposing, lots of tattoos. I look like a Celtic violin player—nobody is gonna listen to me. But they listen to her. She was like, “Hold up. Look up.” She would point up and make [the protesters] look. She goes, “You see those three floors? People live there. Babies, elderly people. So you loot all you want—I’m all for it. But I don’t know which one of you is lighting the fires, and because of that, I’m not going to let you loot this building.”

People would totally just go, “Oh, yeah, thanks, man. That’s cool.” And they would just walk on to the next place.

Every single day I watch people go in and out of these businesses. And I watch the people pissing on the side of the buildings. Last night, I sat up here, and I watched seven kids wander over. I watched them pulling off the plywood. They were stacking the plywood, almost like a little bonfire pile by the door, and going inside. Then, pretty soon, smoke. And then they just moved right on to the next one.

Fires are still smoldering everywhere. Look, the air in my neighborhood is noxious, but I am breathing. And that is more than can be said for George Floyd. I’m breathing a lot more easily than most of the people I’m watching walk around right now.

I’m white. Let me just put that out there. I have not experienced what our black and brown community has experienced—not just this week, but over decades and centuries. I can’t claim to know how that feels, or to have internalized, really, how it feels. That doesn’t mean that we all don’t feel the incredible grief of a really kind, lovely life being snuffed out, for no good reason. It’s heartbreaking, and it’s angering. Part of me understands the need for this explosion of energy.

The police presence wasn’t here for a long, long time. They weren’t here overnight. Then, as soon as the sun came up, all of a sudden there were fire engines. I was like, “Man, where have they been all night?” I understand—having the police here, when the police are the reason people are out, is probably not going to achieve the desired result. But as somebody who is, you know, living in the neighborhood, it is disconcerting to feel that lack of support. But what the hell—what do I think our black and brown communities have been feeling all these decades?

These are moments that teach us, that help us learn. Proximity is a great teacher. I have had so many people say to me, “Are you okay? You should get out.” Or, “Are you are right? We’re sending you love. We’re praying for you.” But I don’t want to get out. I have no interest in getting out. This is my home. This is my neighborhood. I want to be right where I am. Because getting out is part of the problem.