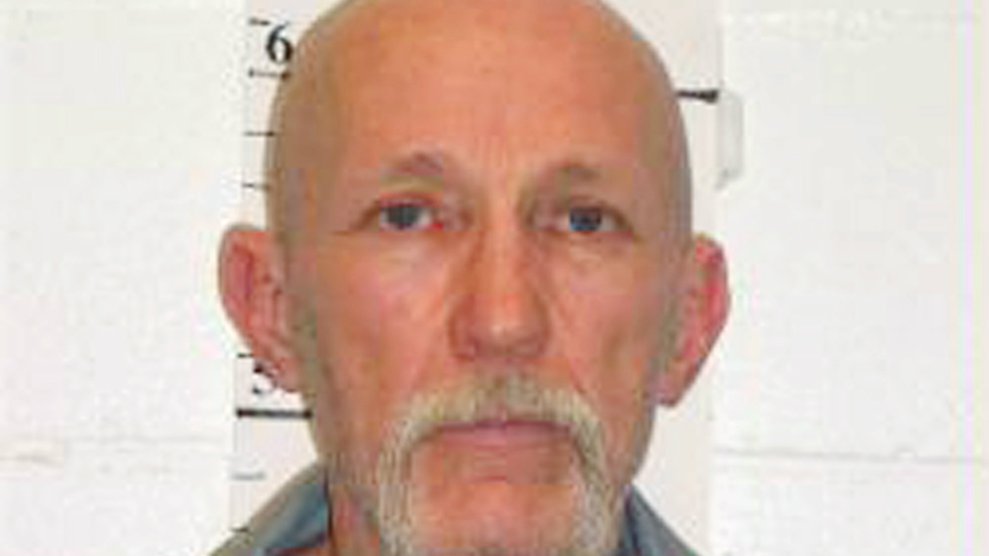

Missouri Department of Corrections/AP

On Tuesday evening, Missouri became the first state to carry out an execution in the midst of a pandemic that has infected 1.5 million people and killed approximately 90,000 in the United States alone. Walter Barton, a 64 year old man was put to death at the Bonne Terre prison for the 1991 murder of 81-year-old Gladys Kuehler.

“Missouri’s plan to resume executions in the midst of a public health crisis and budget shortfalls is actually perfectly indicative of the entire death penalty system,” Hannah Cox, the national manager of Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty, said in a statement prior to the execution. “[It’s] ineffective, unwise, financially reckless, and mostly carried out symbolically to appear tough on crime while actually just wasting resources that could be used to make our communities safer.”

Barton’s execution moved forward attended by prison staff, witnesses, journalists, and others—an ill-advised plan as social distancing is one of the best tools we have to slow the spread of the new coronavirus, which has infected nearly 11,000 and killed 605 people in Missouri. As I reported earlier this month, Missouri doesn’t appear to be making any special accommodations for the procedure, despite prisons being a hotspot for outbreaks:

It’s hard to imagine an appropriately distanced execution in an American prison. In Missouri, the inmate is allowed up to two members of clergy and five friends or relatives to witness his death. Then there are the inmate’s lawyers, the state’s witnesses, members of the media, and the loved ones of the victims. Would it be possible for all of those people to stay safe from COVID-19 inside of a prison? The Missouri Department of Corrections did not respond when asked if it would make any accommodations for this execution.

To complicate matters even further, Barton’s lawyers had said their client was innocent. And they needed time to prove it:

Even without the coronavirus, advocates have argued that Barton did not commit the crime and should not be put to death. In February, Barton’s lawyer Frederick Duchardt Jr. said, “Missouri is about ready to put to death an actually innocent man.” The state relied on a jailhouse informant and blood splatter evidence to convict Barton, both of which are considered to be unreliable. Barton, who has maintained his innocence for nearly 30 years, was tried five times for the murder between 1993 and 2006; the first two ended in mistrials, and his conviction has been overturned twice. His fifth trial ended in conviction.

Last week, Duchardt said three jurors from Barton’s final trial in 2006 admitted they had “misgivings” about the blood splatter evidence.

But still, a federal appeals court rejected his claims of innocence on Sunday and Republican Gov. Mike Parson declined to halt the execution. “The fact that the state of Missouri carried out the execution of Walter Barton tonight, as we face a deadly pandemic, is unconscionable,” the American Civil Liberties Union said in a statement. “By moving forward, the state not only put the health of prison staff at risk and forced them to defy public health guidance, it also refused to consider new, persuasive evidence that Barton may be innocent.”