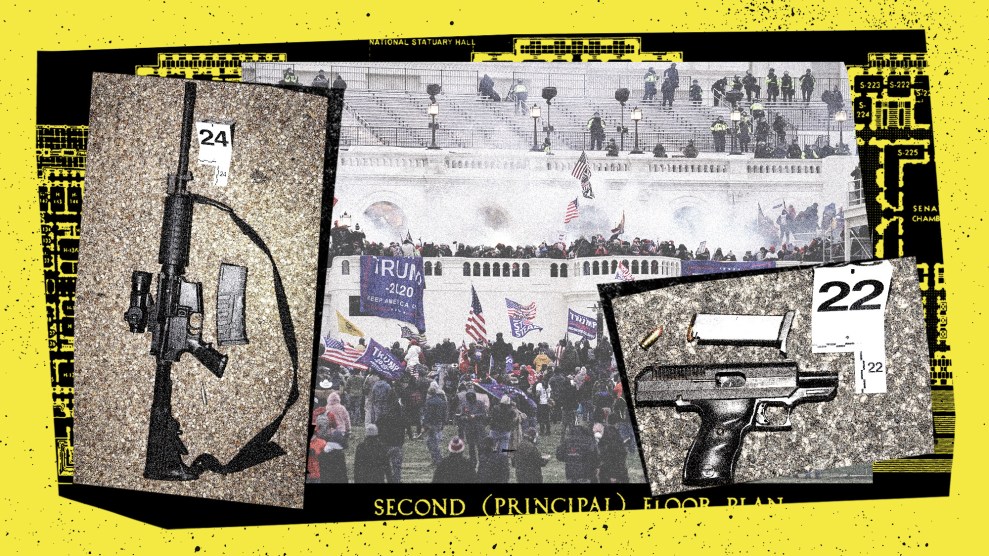

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

At the end of January, a dozen senior staffers at a controversial “personal safety” startup met to tackle an urgent problem: how to turn a profit. Earlier that month, Citizen, whose flagship app offers “instant notifications and live broadcasts of reported crimes and incidents near you,” was trumpeting a new record: During the January 6 Capitol riot, 1.4 million users engaged with the app for real-time updates, video footage, and police radio snippets, its best-ever daily performance. Executives needed to keep that momentum—and the new revenue it brought in.

What the company didn’t announce was how they’d done it—by sending a frightened Washington, DC–based staffer into the violent fray, disguised as a member of the destructive crowd, without protections or safety protocols. “He was there, pretending like he was one of them,” said one former Citizen staffer. “He was just filming and sending those back to central command…A lot of those videos that you saw there were actually from a Citizen employee.” That employee, who didn’t respond to an interview request, reportedly became so frightened for his safety that he fled the scene—while managers in New York were “super excited” that the footage helped bring in millions of clicks and views.

That choice to put clicks ahead of safety, say current and former Citizen staff, is the tip of the iceberg at a troubled company. I spoke with employees and obtained dozens of documents on Citizen’s funding, operations, and corporate culture, many of which demonstrate the lengths to which its management, including CEO Andrew Frame—a serial investor made rich by early Facebook equity—have gone to boost user traffic. (Another early Citizen funder profited hugely from Facebook: venture capitalist and sometime Trump ally Peter Thiel.)

Citizen’s head of central operations, Frame lieutenant Lenny BeckRoda, announced an ambitious goal on the January call: at least $28 million in annual revenue in 2021 and onward. For five years, the firm had run largely on venture capital. Frame, 44, was under increasing pressure to show stakeholders that his company was worth the investment. Citizen’s path to profitability, he’d projected, was to beat that January record each successive month—a tall order. Records show that the company compromised on accuracy, its own privacy policy, and at least one worker’s safety on the way there. “I just knew that the pressure would build significantly within the organization to get to that number at any cost,” said a former staffer who’d joined the January call.

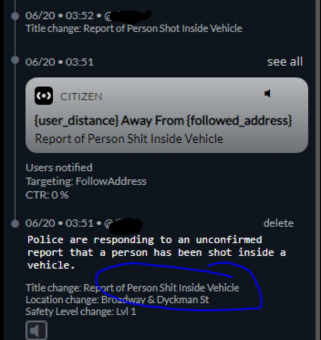

A keystone of Citizen’s service is the push notifications it provides on nearby crime and weather events. When an incident breaks—say a shooting or a fire—users are told to expect real-time updates from analysts tracking police and fire radio scanners. But according to documents assessing incident reports from December 2020 to February 2021, hundreds of alerts containing false information would go out daily, the employees I spoke with said, including incorrect locations and other details, or wholly wrong descriptions of events. The two former staffers I spoke with were “constantly correcting errors on the fly,” one of “the most time-consuming” aspects of their jobs. But that kind of attention, they said, was the exception to the rule.

The most widely publicized false report, first covered by the Verge in May, led to the detention of an innocent man publicly blamed by Citizen for a wildfire burning just miles from a Los Angeles mansion that Frame owned. Citizen published the man’s photograph and made headlines when Frame personally offered a $30,000 bounty for his capture. As users flocked to Citizen’s fire coverage, Frame’s messages grew more animated. “FIND THIS FUCK,” he wrote in a Slack message, Vice reported. “LETS GET THIS GUY BEFORE MIDNIGHT HES GOING DOWN.” The man was later cleared of any connection to the blaze—and the app once again did numbers.

One staff member told me that Frame called them the following night. “He told me he had some friends” who were watching Citizen’s fire coverage together, that staffer said, “and they were all loving it, loving the incident, and they wanted to cast it to a TV screen.” Frame’s friends were watching Citizen’s coverage of the manhunt, according to the staffer, “like sports.” Frame later publicly apologized—but at an all-hands meeting, he insisted the incident had been a “massive net win.” (In a statement, a Citizen spokesperson said that Frame himself did not watch the coverage with friends or in a party atmosphere.)

Citizen’s big draw is its claim to provide “fast, accurate information” that makes “a meaningful difference in emergencies.” But unanimously, the insiders I spoke with believed that Frame was less concerned with accurate crime reporting than with publishing as many reports as possible. (He was reportedly adamant, especially amid the fallout from its highest-profile error, that Citizen was “not a news app—we’re a public safety app.”)

Staff also provided me copies of internal reports that track the accuracy of Citizen’s reporting, assembled by the company’s lone quality assurance specialist. In the first 10 days of January, which included its record-breaking insurrection coverage, documents suggest the company notified users of close to 30,000 incidents. Based on the specialist’s reports, more than 5,500 of those—almost one in five—may have contained factual errors.

The staffer who leaked those records called quality control an “afterthought” at Citizen, and observed that the January meeting was one of many where accuracy wasn’t discussed at all. In one common instance, according to the same person, police broadcasts mentioning a “male stop” were routinely logged as “male stabbed” by inexperienced staff in its New York office. (New analysts in that office were given two weeks’ training in radio before starting to log incidents for the close to 2 million users in Citizen’s largest market.) Two staffers recalled another incident where an analyst reported that a man was shot “in the temple”; he was shot at Philadelphia’s Temple University. Anyone, the two staffers often joked, “could just walk into the central room and type up a notification that a nuclear missile is incoming to Manhattan or Los Angeles…there were no safeguards to that.”

The heavy traffic drawn by this error alerted the analyst responsible to correct it.

Anonymous

Former staffers say there was little internal incentive for accuracy—despite Citizen’s quality assurance specialist regularly pointing out errors. Analysts’ practice of “archiving” incorrect reports helped remove them from the public eye, but made it impossible for anyone outside Citizen to assess the app’s accuracy.

Other analysts, under pressure to ratchet up the number of incidents, would knowingly log prank calls and other false reports—like a litany of calls summoning emergency services to 312 Riverside Drive in Manhattan, an address that doesn’t exist. “Even the cops disregard it,” a former staffer said, “but we still put it in.”

Another former staffer called content moderation similarly insignificant. Citizen’s six moderators were tasked with removing “blood and gore,” as well as unrelated footage of illegal or sexual activity. But the company did little, that staffer said, to moderate a comments section riddled with hate speech, racism, and violent language. And it didn’t always adhere to its own rules, violating internal privacy standards meant to protect the identities of people in videos on at least one major occasion. Frame said he “overrode the policy” the night of the wildfire, when Citizen published the unconfirmed name and image of the supposed arsonist. One moderator, the same source said, objected to the lax enforcement in a Slack message to Frame and other staff. Their plea was ignored.

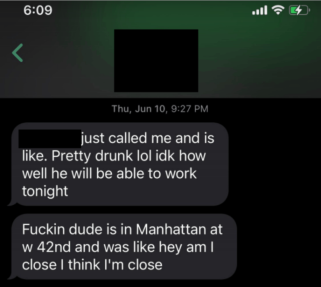

All the current and former staffers also attested to frequent drinking and cannabis use during work hours by both analysts and content moderators. Moderators, especially on overnight shifts that ran till 6 a.m., sometimes encountered images and footage of police violence, dead bodies, and other graphic content. For the short-staffed team, sources said working drunk or high was a popular way to cope. A Citizen spokesperson responded to questions about worker allegations in part by saying the company pledges “to improve on any support offerings that may be needed.”

In the aftermath of the fire incident, two of the former staff who spoke with me became disheartened with the way the startup operated: the CEO’s unpredictable behavior, the long hours monitoring crime and disaster footage, and their sense that management relished tragedy-driven user engagement. They weren’t alone. According to two former staffers and an anonymous tip, at least 15 of Citizen’s analysts and moderators quit or were fired in 2021. The same tip claimed that Kenya- and Nepal-based contractors working with Citizen through a third-party outsourcing firm were quitting “en masse due to horrible working conditions and lack of support”; according to both an internal source and employment websites like Glassdoor, the contractors earn a fraction of US analysts’ $55,000 base salary. Two former staffers confirmed that contractors had resigned in large numbers.

Citizen’s US staff, upset with labor conditions, benefits cuts, and the prospect of further outsourcing, recently filed to unionize with the Communications Workers of America. Executives have refused to recognize the union, though more than 60 of its approximately 70 analysts and moderators have signed union cards. A Citizen statement opposing “meddling from an outside union” suggests that the company’s management has no plans to budge.

Union or no union, Citizen’s future depends on its profitability. As of late August, the firm was $16 million short of its $28 million target, partly due to lower-than-anticipated returns on “Protect,” a $20-per-month feature that lets users speak with its analysts on demand—just 28 percent of those users paid for subscriptions after their free trials ended. “The biggest problem Citizen faces,” according to one former staff member, “is that the app solves nothing. It’s so useless.”

The same ex-staffer said that Citizen’s model amounts, whether or not by design, to building what company analysts call “the fear machine”—a “perfect product feedback loop” that helps sustain revenue. Constant crime notifications can intensify users’ senses of fear and pervasive danger, giving them more incentive to buy premium features like Protect. “I felt like we’re not only distributing the heroin for free,” the staffer said, “we’re selling the Narcan.”