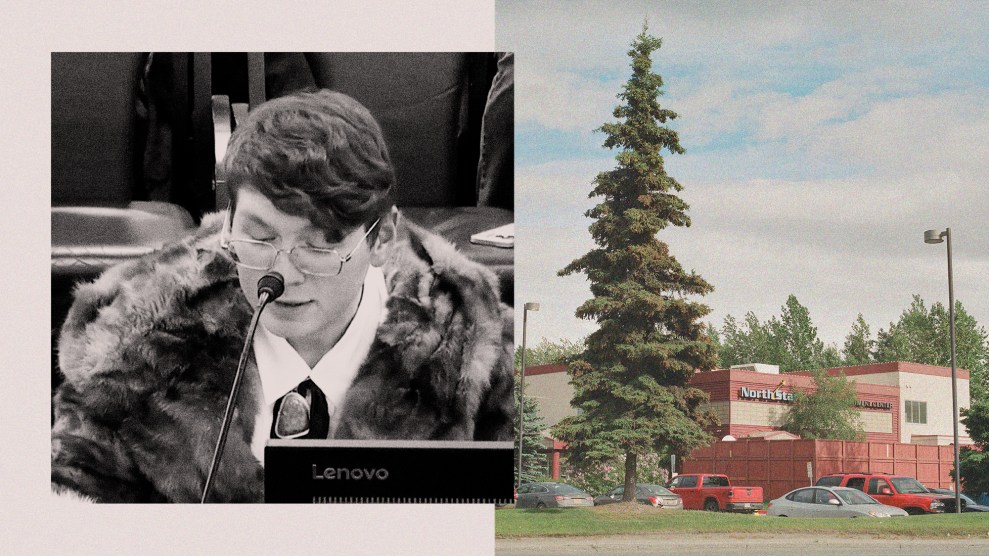

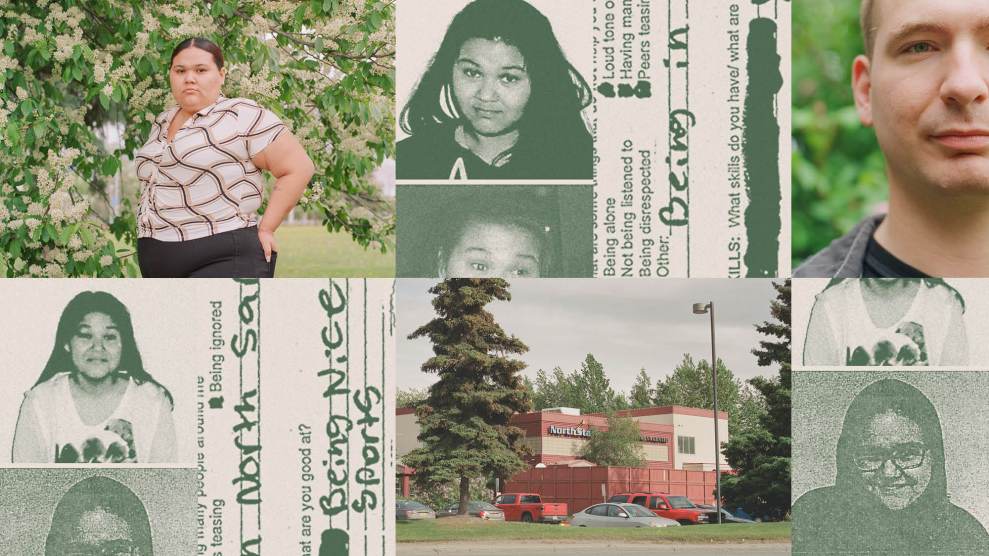

Trina Edwards is a former foster kid who first was admitted to a UHS psychiatric hospital in Alaska when she was 12.Mother Jones illustration; Ash Adams

This week on Reveal, reporter Julia Lurie reports on how Universal Health Services, the largest psychiatric hospital chain in the country, profits off of foster kids who are admitted to its facilities.

Lurie’s reporting reveals a symbiotic relationship between child welfare agencies, which don’t have enough foster homes for all the kids in custody, and large for-profit companies like Universal Health Services, which have beds to fill. Children admitted to UHS facilities have reported on the use of violent restraints and being put in seclusion rooms, among other alarming allegations (UHS has said it complies with regulations related to some of these practices and is committed to reducing the use of restraints and seclusion). Even though government and media reports have documented these complaints, Lurie’s investigation found that some foster kids continue to spend months or even years in United Health Services facilities.

One of those kids was Trina Edwards, a former foster kid who first was admitted to a UHS psychiatric hospital called North Star in Alaska when she was 12. In this podcast episode, an updated version of a previous show, Lurie speaks to Edwards about her experience.

Since this episode first aired in October, two bills have been introduced in Alaska’s state legislature that aim to address some of the problems Lurie worked to uncover. Lurie wrote about the proposed legislation earlier this month:

Though neither bill mentions North Star by name, it looms large as the state’s only private psychiatric hospital for children.

HB 363 would require a court to review a foster child’s placement at a psychiatric hospital within 72 hours to determine if that child meets medical criteria for hospitalization. (There’s no statute on when an initial hearing should take place, though a preliminary injunction requires a hearing within 30 days.)

A second bill, HB 366, would require health department employees to conduct unannounced visits to residential psychiatric facilities at least twice a year, and to interview at least half of the patients during such visits. It would also require facility staff to report incidents of seclusion or restraint to the state within a day of the incident, and allow weekly, confidential video visits with parents or guardians. Rep. Maxine Dibert, a Fairbanks Democrat and the legislature’s sole female Alaska Native lawmaker, was reportedly inspired to introduce the bill by the prevalence of Native children in psychiatric residential treatment facilities. (The same legislation was also introduced in the Senate.)