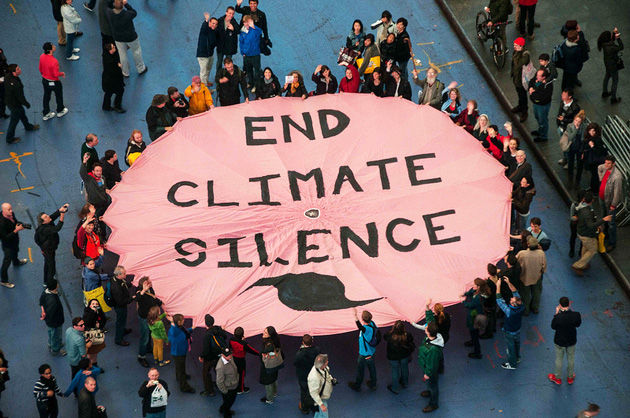

Demonstration of environmental activists in Times Square after Hurricane Sandy. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/350org/8132412591/sizes/c/in/photostream/">350.org</a> / Flickr

This article first appeared in the Guardian as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A Harvard academic has put the blame squarely for America’s failure to act on climate change on environmental groups. She also argues that there is little prospect Barack Obama will put climate change on the top of his agenda in his second term.

In a research paper, due to be presented at a Harvard forum next month, scholar Theda Skocpol in effect accuses the DC-based environmental groups of political malpractice, saying they were blind to extreme Republican opposition to their efforts.

Environmental groups overlooked growing opposition to environmental protections among conservative voters and underestimated the rising force of the tea party, believing—wrongly, as it turned out—they could still somehow win over Republican members of Congress through “insider grand bargaining.”

That fatal misreading of the political realities—namely, the extreme polarization of Congress and the tea party’s growing influence among elected officials—doomed the effort to get a climate law through Congress. It will also make it more difficult to achieve climate action in the future, she added.

Skocpol, meanwhile, lets Obama off the hook for the political inaction on climate change, overturning the conventional wisdom among environmental leaders that political cowardice by the White House ultimately doomed climate legislation.

Her paper is likely to cause a stir among environmental groups hoping to see action on climate change during Obama’s second term. Skocpol, in her analysis, does not offer much cause for optimism.

“Whatever environmentalists may hope, the Obama White House and congressional Democrats are unlikely to make global warming a top issue in 2013 or 2014,” she writes.

The extreme weather events of the 2012, from Superstorm Sandy to an historic drought, are unlikely to shift their priorities, she said.

“The stark truth is that severe weather events alone will not cause global warming to pop to the top of the national agenda,” Skocpol went on. “Fresh strategies will be needed, based on new understandings of political obstacles and opportunities.”

Skocpol, a political scientist, compares the failed push for a climate law unfavorably to the ultimately successful effort to pass health care reform.

She interviewed key players in the push for climate legislation in 2009 and 2010, as well as activists from the tea party groups who helped sink those efforts.

The biggest mistake of the environmental groups, Skocpol said, was their failure to appreciate the extreme polarization of Congress since the mid-’90s, or fully appreciate that Republicans in Congress were softening in their support for environmental issues from 2007—even before the emergence of the tea party.

That political blindness was far more damaging to the effort to pass a climate law than the economic downturn, the language used to frame the climate change debate, or even the lack of full-throated leadership from Obama, she argues. A deal that may have been possible in the ’90s was going to be a nonstarter amid the political conditions in 2008, she said.

Nevertheless, the US Climate Action Partnership (USCAP), which Skocpol describes as a coalition of “CEOs and Big Enviro honchos,” continued to believe it could wrangle exactly such a deal out of Congress.

That strategy overlooked how the political reality outside clubby Washington had turned against their cause. Skocpol attributes much of that shift to the well-funded effort by conservative think tanks to undermine climate science. The ’90s and onwards saw a sharp increase in the publication of reports and books questioning climate change, which eventually got picked up by mainstream media outlets.

The USCAP never understood the shift in conservative popular opinion, she writes. They also failed to build the broad grassroots organizations needed to push for change.

“The USCAP campaign was designed and conducted in an insider-grand-bargaining political style that, unbeknownst to its sponsors, was unlikely to succeed given fast-changing realities in US partisan politics and governing institutions,” Skocpol writes. And she warns the failed attempt “did much to provoke and mobilize fierce enemies and enhance their populist capacities and political clout for future battles.”

A number of prominent Republicans who had support climate legislation had already turned away by 2007—not least of all John McCain, who was Obama’s opponent in 2008. McCain’s choice of Sarah Palin as his vice president, who is famous for her “drill, baby, drill” comments, should have alerted environmental groups to changing politics around the environment, Skocpol writes.

The writing was on the wall even more starkly after 2010, when a number of Republicans who had previously compromised on environmental issues were defeated by more conservative primary challengers, and by the stunning wins for tea-party-supported candidates in the congressional elections.

Skocpol’s recommendations for environmental groups are stark. “Climate change warriors will have to look beyond elite maneuvers and find ways to address the values and interests of tens and millions of US citizens,” she writes.

“Reformers will have to build organizational networks across the country, and they will need to orchestrate sustained political efforts that stretch far beyond friendly congressional offices, comfy board rooms, and posh retreats.”

She concludes: “The only way to counter such right wing elite and popular forces is to build a broad popular movement to tackle climate change.”

Climate activist Bill McKibben said Skocpol’s analysis mirrored his experiences in building the grassroots organization 350.org.

“Basically, we need a movement, and we need something a movement can get behind,” he said in an email. “Something people as compared to corporations might care about.”

McKibben wrote a more detailed response on the environmental news site Grist.