<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=637862&src=id">Mary Lane</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the Guardian website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Sabrina Warner keeps having the same nightmare: a huge wave rearing up out of the water and crashing over her home, forcing her to swim for her life with her toddler son.

“I dream about the water coming in,” she said. The landscape in winter on the Bering Sea coast seems peaceful, the tidal wave of Warner’s nightmare trapped by snow and several feet of ice. But the calm is deceptive. Spring breakup will soon restore the Ninglick River to its full violent force.

In the dream, Warner climbs on to the roof of her small house. As the waters rise, she swims for higher ground: the village school which sits on 20-foot pilings.

Even that isn’t high enough. By the time Warner wakes, she is clinging to the roof of the school, desperate to be saved.

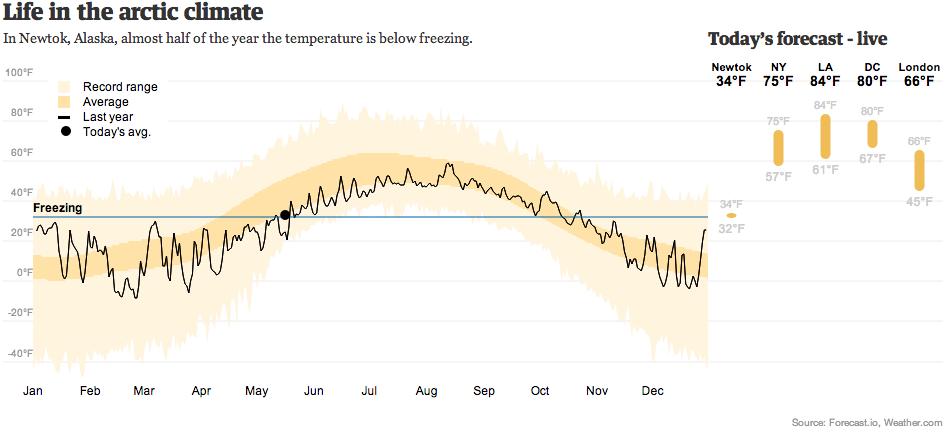

Warner’s vision is not far removed from a reality written by climate change. The people of Newtok, on the west coast of Alaska and about 400 miles south of the Bering Strait, which separates the state from Russia, are living a slow-motion disaster that will end, very possibly within the next five years, with the entire village being washed away.

The Ninglick River coils around Newtok on three sides before emptying into the Bering Sea. It has steadily been eating away at the land, carrying off 100 feet or more some years, in a process moving at unusual speed because of climate change. Eventually all of the villagers will have to leave, becoming America’s first climate change refugees.

It is not a label or a future embraced by people living in Newtok. Yup’ik Eskimo have been fishing and hunting by the shores of the Bering Sea for centuries and the villagers reject the notion they will now be forced to run in chaos from ancestral lands.

But exile is undeniable. A report by the US Army Corps of Engineers predicted that the highest point in the village—the school of Warner’s nightmare—could be underwater by 2017. There was no possible way to protect the village in place, the report concluded.

If Newtok can not move its people to the new site in time, the village will disappear. A community of 350 people, nearly all related to some degree and all intimately connected to the land, will cease to exist, its inhabitants scattered to the villages and towns of western Alaska, Anchorage, and beyond.

It’s a choice confronting more than 180 native communities in Alaska, which are flooding and losing land because of the ice melt that is part of the changing climate.

The Arctic Council, the group of countries that governs the polar regions, are gathering in Sweden today. But climate change refugees are not high on their agenda, and Obama administration officials told reporters on Friday there would be no additional money to help communities in the firing line.

On the other side of the continent, the cities and towns of the East Coast are waking up to their own version of Warner’s nightmare: the storm surges demonstrated by Hurricane Sandy. About half of America’s population lives within 50 miles of a coastline. Those numbers are projected to grow even more in the coming decades.

What chance do any of those communities, in Alaska or on the Atlantic coast, have of a fair and secure future under climate change, if a tiny community like Newtok—just 63 houses in all—cannot be assured of survival?

But as the villagers of Newtok are discovering, recognizing the gravity of the threat posed by climate change and responding in time are two very different matters.

Remote location

Newtok lies 480 miles due west of Anchorage. The closest town of any size, the closest doctor, gas station, or paved road, is almost 100 miles away.

The only year-round link to the outside world is via a small propeller plane from the regional hub of Bethel.

The seven-seat plane flies over a landscape that seems pancake flat under the snow: bright white for land, slightly translucent swirls for frozen rivers. There are no trees.

The village as seen from the air is a cluster of almost identical small houses, plopped down at random on the snow. The airport is a patch of ground newly swept of snow, marked off for the pilot by a circle of orange traffic cones. The airport manager runs the luggage into the center of the village on a yellow sledge attached to his snowmobile.

Like many if not most native Alaskan villages, Newtok owes its location to a distant bureaucrat. The Yup’iks, who had lived in these parts of Alaska for hundreds of years, had traditionally used the area around present-day Newtok as a seasonal stopping-off place, convenient for late summer berry picking.

Even then, their preferred encampment, when they passed through the area, was a cluster of sod houses called Kayalavik, some miles further up river. But over the years, the authorities began pushing native Alaskans to settle in fixed locations and to send their children to school.

It was difficult for supply barges to maneuver as far up river as Kayalavik. After 1959, when Alaska became a state, the new authorities ordered villagers to move to a more convenient docking point.

That became Newtok. Current state officials admit the location—on low-lying mud flats between the river and the Bering Sea—was far from perfect. It certainly wasn’t chosen with a view to future threats such as climate change.

“The places are often where they are because it was easy to unload the building materials and build the school and the post office there,” said Larry Hartig, who heads the state’s Commission on Environmental Conservation. “But they weren’t the ideal place to be in terms of long-term stability, and it’s now creating a lot of problems that are exacerbated by melting permafrost and less of the seasonal sea ice that would form barriers between the winter storms and uplands.”

It became clear by the 1990s that Newtok—like dozens of other remote communities in Alaska—was losing land at a dangerous rate. Almost all native Alaskan villages are located along rivers and sea coasts, and almost all are facing similar peril.

A federal government report found more than 180 other native Alaskan villages—or 86 percent of all native communities—were at risk because of climate change. In the case of Newtok, those effects were potentially life-threatening.

A study by the US Army Corps of Engineers on the effects of climate change on native Alaskan villages, the one that predicted the school would be underwater by 2017, found no remedies for the loss of land in Newtok.

The land was too fragile and low-lying to support sea walls or other structures that could keep the water out, the report said, adding that if the village did not move, the land would eventually be overrun with water. People could die.

It was a staggering verdict for Newtok. Some of the village elders remember the upheaval of that earlier move. The villagers were adamant that they take charge of the move this time and remain an intact community—not scatter to other towns.

And so after years of poring over reports, the entire community voted to relocate to higher ground across the river. The decision was endorsed by the state authorities. In December 2007, the village held the first public meeting to plan the move.

The proposed new site for Newtok, voted on by the villagers and approved by government planners, lies only nine miles away, atop a high ridge of dark volcanic rock across the river on Nelson Island. On a good day in winter, it’s a half-hour bone-shaking journey across the frozen Ninglick River by snowmobile.

But the cost of the move could run as high as $130 million, according to government estimates. For the villagers of Newtok, finding the cash, and finding their way through the government bureaucracy, is proving the challenge of their lives.

Five years on from that first public meeting, Newtok remains stuck where it was, the peeling tiles and the broken-down office furniture in the council office grown even shabbier, the dilapidated water treatment plant now shut down as a health hazard, an entire village tethered to a dangerous location by bureaucratic obstacles and lack of funds.

Village leaders hope that this coming summer, when conditions become warm enough for construction crews to get to work, could provide the big push Newtok needs by completing the first phase of basic infrastructure. And the effort needs a push. When the autumn storms blow in, the water rises fast.

Changing climate

Climate change remains a politically touchy subject in Alaska. The state owes its prosperity to the development of the vast Prudhoe Bay oil fields on the Arctic coast.

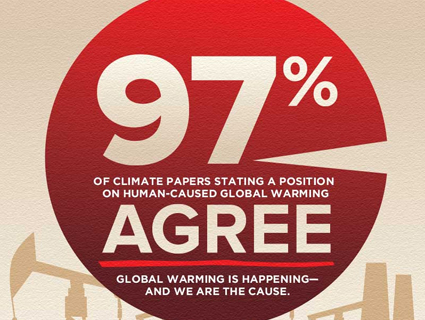

Even in Newtok, there are some who believe climate change is caused by negative emotions, such as anger, hate, and envy. But while some dispute the overwhelming scientific view that climate change is caused primarily by human activities, there is little argument in Alaska about its effects.

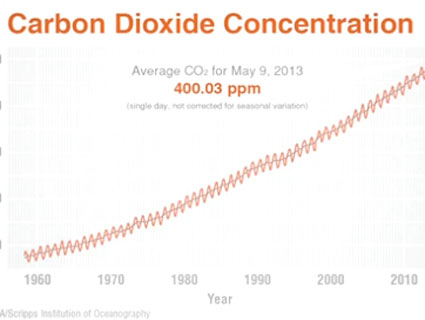

The state has warmed twice as fast as the rest of the country over the past 60 years. Freeze-up occurs later, snow is wetter and heavier. Wildfires erupt on the tundra in the summer. Rivers rush out to the sea. Moose migrate north into caribou country. Grizzlies mate with polar bears as their ranges overlap.

Even people in their 20s, like Warner and her partner, Nathan Tom, can track the changes in their own lifetimes. Tom said the seasons have changed. “The snow comes in a different timing now. The snow disappears way late. That is making the geese come at the wrong time. Now they are starting to lay their eggs when there is still snow and ice and we can’t go and pick them,” Tom said. “It’s changing a lot. It’s real, global warming, it’s real.”

On days when the clouds move in, and the only sound is the crunch of boots on snow and the distant buzzing of snowmobiles, it’s difficult to imagine a world beyond the village, let alone a threat.

But Warner has seen the river rip into land and carry off clumps of earth. “It’s scary thinking about summer coming,” she said. “I don’t know how much more is going to erode—hopefully not as much as last year.”

Warner was raised in Anchorage and Wasilla, mainly by her non-Yup’ik father. But she was introduced to Yup’ik food and Yupi’ik ways by her mother, and she has taken to village life since moving to Newtok in December 2011 to be with Tom.

Even in those short months, she said she can see the changes carved out on the land behind the family home. “When I first got here the land used to be way out there,” she said, pointing towards the west. “Now that doesn’t exist any more. There is no land there any more.”

The river claims more of the village every year. Warmer temperatures are thawing the permafrost on which Newtok is built, and the land surface is no longer stable. The sea ice that protected the village from winter storms is thinning and receding, exposing Newtok to winter storms with 100 mph winds and the waves of Warner’s nightmare.

When the wind blows from the east or south, the land falls away even faster. The patch of land where Warner picked last summer to practice shooting was gone, on the other side of a sharp drop-off to the river. “The summer came, 15 or 20 feet of land went just from melting, and then after we had those storms in September, another 20 feet went,” she said. In an average year the river swallows 83 feet of land a year, according to a report by the Government Accountability Office. Some years, of course, it’s more.

The reddish-brown house where Tom and Warner live with their son, Tyson, and elderly relatives is the closest in the village to the Ninglick.

Warner fears her house will soon be swallowed up by that hungry river. “Two more years, that’s what I’m guessing. About two more years until it’s right up to our house,” she said.

The house is now barely 200 paces away from the drop-off point. It’s become a sort of tourist stop for visitors to the village, and an educational aid for teachers at the local school. Last year, one of the teachers set out stakes to mark how fast the river was rising. At least one has already been washed away.

But it won’t be long before nobody in the village is safe. Other homes, once considered well back from the river, now regularly flood.

Over the years the river, in its attack on the land, engulfed a few small ponds—some fresh water, some used as raw sewage dumps—spewing human waste across the village. Last summer it almost carried off a few dumpsters filled with old fridges and computers. It swept away the barge landing, and infested the landfill.

Sometimes, though, the river gives up treasure: villagers walking newly exposed banks have discovered mammoth tusks and fossil remains.

During one storm last autumn, Warner stayed up until 4 a.m., waiting to see if the waves would engulf the house. “I was scared because it looked so close because our window is right there. I was just looking out, and you can see these huge waves come at you,” she said.

It’s not easy living with that fear every day, she concedes. Anxious residents want to know that their future will be safe. They are exhausted by the years of uncertainty and fed up with a village left to decay, with leaders’ energy and every scrap of funding focused on the relocation.

“Considering that our house is the closest, I would like it if they would at least let us know if we are going to have a house over there [at the new site],” said Warner. Tom’s grandmother, who needs supplemental oxygen, lives with the couple. It would be tough to move her in the event of a disaster, although she claims she is not at all afraid.

The young couple go through times when they can’t deal with the talk of relocation. Tom bought a big tent some time ago, and he and Warner talked about camping out at the site chosen for the new village, just to get away—from the stress, from the drama of village politics—until things are settled.

But the relocation keeps being put off.

“A few years ago, they said next year. And then last year they said next year. And next year, they are probably going to say next year again,” said Tom. But he soon perks up. The village has sent local men, including Tom, for training as construction workers.

“It’s picking up,” he said. “I’m not afraid anymore. The erosion is really fast. I know the state is going to deal with it pretty fast. They are not going to leave us hanging there.”