<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-220618249/stock-photo-wind-turbines-silhouette-at-sunset.html?src=4fI9eK49X_8BRrXv2CmSoA-1-16">SUWIT NGAOKAEW</a>/Shutterstock

With high-stakes climate negotiations just around the corner, things are looking rosy for the producers and sellers of wind turbines and solar panels.

In just a couple weeks, world leaders will gather in Paris to hash out a global agreement to combat climate change. On Thursday, top diplomats from the United States and France appeared to butt heads over the legal status of the agreement, with French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius criticizing a statement made by Secretary of State John Kerry that the greenhouse gas reduction targets in the agreement will not be legally binding.

Each party to the agreement offers its own target based on its abilities. The US, for example, has committed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. The targets are a key piece of the agreement, since they represent countries’ plans to limit the emissions that cause climate change.

The targets offered so far—known in UN jargon as intended nationally determined contributions, or INDCs—have faced criticism from environmental groups, in part because it remains unclear how they will be enforced, as Kerry’s spat with the French makes clear. Moreover, cumulatively, they don’t put the world on track to limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, as scientists and diplomats have agreed is necessary to avert the worst impacts of climate change.

But that hardly means the agreement will be worthless. The INDCs also include information about how countries plan to reach their emissions targets. And as several recent reports have helped to illustrate, the Paris talks could be a huge boon to the global clean energy industry—an industry that was worth about $270 billion as of 2014 and is growing fast.

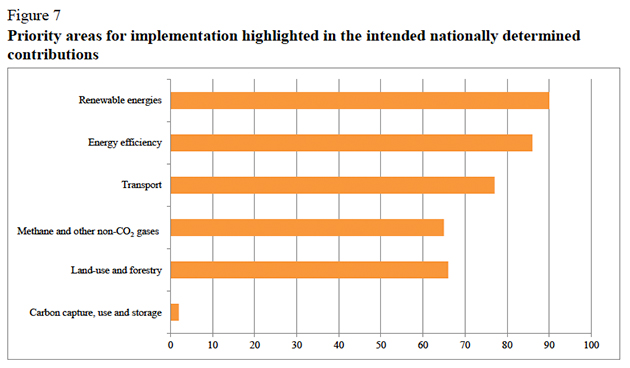

The first sign came from a United Nations analysis in late October, which combed through INDCs from almost every country on Earth and found that most of them include plans to invest in renewable energy within their borders. Some of those plans include specific policies—such as providing tax incentives or drawing on international aid dollars—and some more vague. Taken together, renewable energy appears to be the most common strategy for meeting emissions targets, compared to boosting energy efficiency, cleaning up the transportation sector, stopping deforestation, and other methods:

“Clearly countries are looking at renewables as a solution to tackle the energy challenges they’re facing,” said Thomas Damassa, a senior analyst at the World Resources Institute’s climate program. “It’s clearly something that’s on all countries’ minds, not a device for only the rich. It’s a viable option for all countries.”

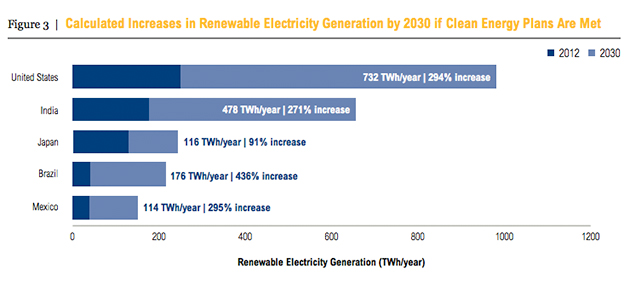

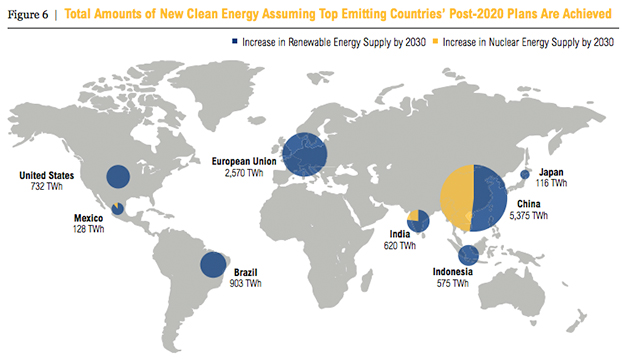

According to Damassa’s research, if Brazil, China, the European Union, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, and the United States—which together represent 65 percent of global energy demand—follow through on their INDCs, the amount of clean energy on the grid will more than double by 2030. That represents an increase from approximately 8,900 terawatt-hours of global clean energy in 2012 to 19,900 terawatt-hours in 2030. (The US currently consumes about 4,000 terawatt-hours of total electricity—from renewable and non-renewable sources.) The chart below illustrates the projected change in a few of these countries:

Different countries have different definitions of “clean energy.” For example, the US is the only one of Damassa’s countries that doesn’t count large hydro dams. India, China, and Mexico include nuclear power plants. In fact, China plans to increase its supply of nuclear power nearly 900 percent, Damassa found, accounting for nearly half of its total clean energy by 2030. That would be a big win for the climate, because nuclear power doesn’t emit greenhouse gases, regardless of concerns about cost and safety.

Damassa found that the renewable capacity implied by these countries’ INDCs is about 17 percent higher than the “business-as-usual” case, meaning that the Paris targets could have a significant impact on the industry’s growth. Much of that extra growth could take place in countries such as India and Brazil that didn’t previously have aggressive clean energy targets.

The impact of the United States’ INDC may more muted. That target is based on the projected outcome of the Clean Power Plan, President Barack Obama’s flagship climate regulations, which will limit greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector. Under that plan, the US aims to get 20 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2030, up from 7 percent now. Environmentalist have criticized that goal as not being ambitious enough.

“In our view, the targets set by the [Clean Power Plan] are not terribly stringent above and beyond what we anticipate will occur in the marketplace anyway,” said Ethan Zindler, the head of policy at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Still, in the face of repeated attacks on federal tax credits and state-level clean energy policies, the INDC could be an important backstop, Zindler said, because it “adds greater certainty around renewables into the next decade.”

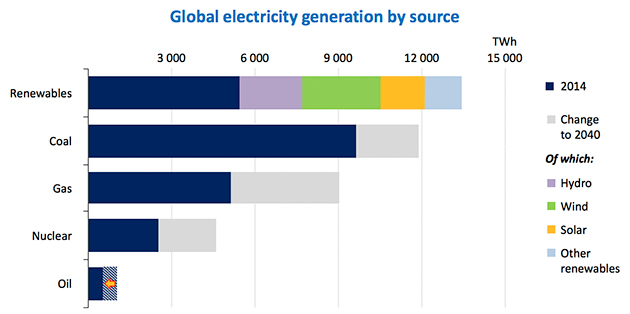

In any case, the INDCs are just one piece of the puzzle. There’s little doubt about which direction the clean energy industry is headed, according to a projection released this week by the International Energy Agency. That report predicts global investment in clean energy will reach $7.4 trillion by 2040, by which time renewables will provide about a quarter of the world’s electricity. Wind is likely to be the biggest new source, according to the IEA:

The IEA’s analysis includes the INDC targets, which it says “provide a boost to lower-carbon fuels and technologies in many countries.” But it also cites falling prices for both renewable technology and for natural gas (which integrates more easily with renewables on the grid than coal does) as major drivers of the industry’s growth.

Tom Kimbis, vice president of executive affairs at the Solar Energy Industries Association, a trade group, argues that the clean energy industry is already prepared to compete in the global market—with or without political targets. Still, he concedes that at the moment, it’s difficult for companies to make decisions about investing in clean energy projects abroad because the details behind many INDCs remain murky.

It’s worth noting that IEA projections are notoriously conservative. In the past, the agency has often dramatically low-balled the growth of wind and solar, so there’s reason to think the final outcome could be even bigger than what that group is projecting. (David Roberts at Vox has an exhaustive explainer on what goes wrong in their analyses.)

The simple fact that renewable energy shows up in so many INDCs is a compelling sign of hope for the industry, Damassa said. Back in 2009, at the last major climate talks in Copenhagen, there was nowhere near this level of interest in clean power, he said.

“People never would have guessed that renewables would be deployed as quickly as they are,” Damassa said.