More than five years ago, the MeToo movement exploded and our culture shifted. But what actually changed? This project seeks to reexamine the era by asking how it will alter the lives of the next generation.

During a 1999 weeks-long expedition to Antarctica with her adviser, Boston University professor David Marchant, Jane Willenbring says she was repeatedly harassed by him, both verbally and physically. At the time, as an earth sciences graduate student and the only woman on a four-person team on the trip, she feared that if she reported the abuse, Marchant would retaliate and block her from advancing in her career.

Nearly 20 years later, after a poignant moment with her 3-year-old daughter, Willenbring reported Marchant to BU, in October 2016. A year later, when contacted by Science magazine, Willenbring went on the record, allowing the magazine to publish her name alongside the experiences of two other women in a story titled “Disturbing allegations of sexual harassment in Antarctica leveled at noted scientist.” Both BU and Marchant declined to discuss the case with Science. But in 2019, Marchant issued a statement through his lawyer, Jeffrey Sankey, saying he has “never” engaged in any form of sexual harassment, “not in 1998 or 1999 in Antarctica or at any time since,” Science reported. (Sankey did not respond to a request for comment from Mother Jones for this article, and Marchant could not be reached for comment.)

After the Science story ran in 2017, the National Science Foundation, among the largest funders of scientific research in the country, announced a big change: NSF-funded academic institutions would be required to notify the agency if a scholar is found to have committed any form of harassment, so that the foundation can take the information into account when making funding decisions. After an investigation, Marchant was let go from BU. (BU did not respond to a request for comment from Mother Jones.)

I reached out to Willenbring, who is now an associate professor of earth and planetary sciences at Stanford University, for her thoughts about her decision to come forward, how she thinks the MeToo movement shaped the public response to the Science article, and if anything has changed for survivors of sexual harassment in the scientific community in the last 20 years.

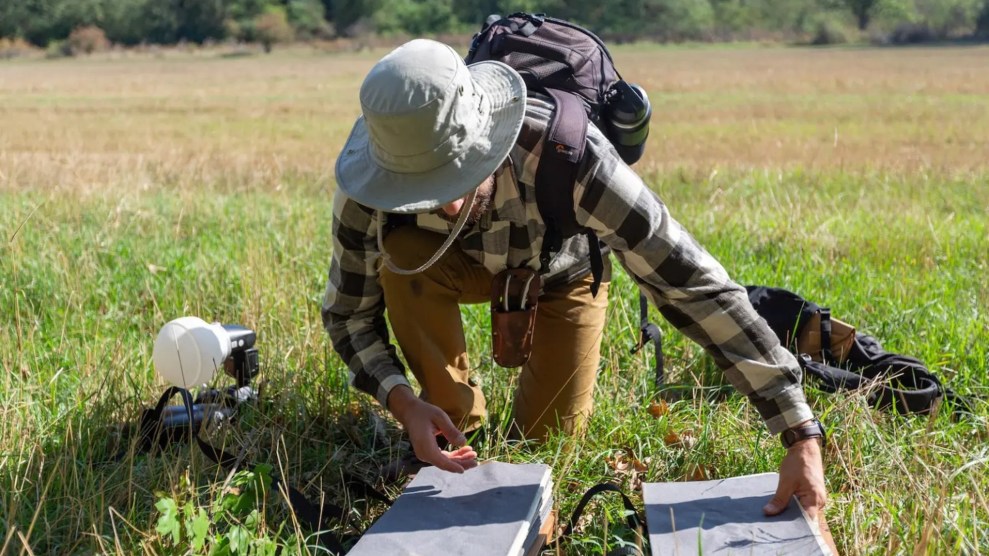

After finishing my undergrad in the ’90s, I wanted to help understand the huge change that the climate was going to go through in the coming decades. I decided to do my master’s degree looking at ice sheet history in Antarctica.

I had two options. I had been talking to Dave Marchant at Boston University, where I was accepted. And there was another school where, when I was visiting, a woman took me aside and said about my potential advisor, “Don’t come here. He sexually harasses women.” And so, even though I hadn’t visited BU, I was like, Well, I’ll go to the place where I don’t have to deal with a sexual harasser. Unfortunately, it ended up not being much of a choice.

I was excited about Antarctica. Back then I was really interested in adventure and traveling. I enjoyed physical tests. I liked camping and I was very outdoorsy and loved to hike. I wasn’t too worried about the cold either, because I’m from North Dakota. And I was trying to do my best to impress people in my department and Dave in particular. I wanted to make a good impression.

The farther we went from Boston, the less professional he started to get. He would say, “What happens in the field stays in the field.” And he was really keen on “breaking me down and building me up in his image.” It was sort of like hazing, basically, like sometimes being asked to do push-ups before getting breakfast. Some of it was just to be mean, like calling me a “slut” and a “whore” almost daily.

He was also really focused on my romantic life. He wanted to set me up with his brother. He mentioned how big his brother’s penis was, and that he would be a good choice for me. And I had to sleep in the same tent as his brother. So that was a strange attempt at matchmaking, I would say.

Jane Willenbring, as an earth sciences graduate student

Photo courtesy of Jane Willenbring

And he would get very ragey sometimes. One time, I was with a colleague, mapping some granites that were found near my field site. I was trying to figure out where they came from, which is routine. But when he caught up with us, I was told that I was a stupid fucking whore. And that he should just send me home. It was an incredibly scary event.

There was another instance where we were looking for volcanic ash in a moraine, which is the edge of a former glacier. If we found glacial material that had ash in it, the ash could be dated to help us determine when the glacier was in place. And so we were carefully collecting this delicate ash, which has little shards of mineral crystals and volcanic glass in it. He put some on a spoon and asked me to look at it, and then he blew the puff in my eye. And my eyes were already super sensitive because I had ice blindness. It was just so painful. After that, he apologized and said it went too far.

Sometimes, I’d go to the bathroom, and he would throw rocks at me. So I tried to limit my water consumption. I would just drink when I got back to camp. I would try to pee only when I had privacy. And I got a really bad bladder infection from that. I was peeing blood.

At one point, he pushed me down on the ground and was kneeling on my wrists, sitting over me. And he actually spit on my face. He was trying to do that thing where the spit dribbles out of your mouth a little bit, and then you suck it back in. But he didn’t suck it back in on time. And it actually fell on my face. On another occasion, he waited for me at the top of a hill, grabbed the back of my backpack, and used the little handle to throw me down. It was a pretty steep hill, and I twisted my arm and hurt my knee. At the bottom of the hill, I just wept.

I’m not one to just take things like that. I imagined different things that I could do to stick up for myself. I thought, well, if I do this, then he’s going to do that. And then I’m not going to have a future in academia. It all led me back to, I just have to get through it, get back to BU, finish my degree, and move on with my life.

If I had reported this in 1999, I think it would have gone badly. I don’t think anything would have happened to punish Marchant. I think that he would have retaliated and made sure that I left science.

I had wanted to do my PhD in Antarctica because it was so incredibly important. But after getting back, I thought, “Even if I’m in a different department, I just don’t even want to see him on base. I don’t want him reviewing my grant proposals and my papers, I just want to move away from that entire community.” And so I applied to do my PhD at a different university where I could work in the Arctic and sub-Arctic.

I went to Dalhousie University, which is in Halifax, Nova Scotia. And I’d kind of chosen my adviser because he was a nice guy. He was really great at what he did, but the fact that he was a really nice guy was one of the main selling points.

I always told myself that I was going to do something and report the harassment. That was one of the ways that I made it through, like, I’ll do something about this later when I don’t fear for my future and my safety.

Eventually, I applied for a professorship at the University of California, San Diego, and they hired me with tenure. It was kind of in the back of my head, that I was able to do something. A few months later, I took my daughter, who was maybe three years old, with me to the lab. She saw me in my gloves and lab coat and said, “Mommy, you really are a scientist. I want to be a scientist just like you.” All of a sudden, this precious little person—what if she has an adviser like Dave? And so I started crying. I told her that they were happy tears because I would love it if she was a scientist. But really, I was scared for her.

That night I wrote the first draft of the Title IX report that I would eventually submit to the Title IX office and dean at BU.

I didn’t share my story with the media. Someone else did. I still don’t know who that was. Meredith Wadman from Science contacted me and said that she was doing a story [about Marchant] and she wanted to know if she could include my name in it. I agreed because I thought that it might lend credibility to the allegations if people knew that it was coming from me because I’m not a bullshitter.

I decided that I was fine with all of the possible scenarios that could come from it. One was that people would look at me differently from now on. That happened. And I got some death threats delivered to my mailbox at work, written on my door. Die cunt was one of them.

But I completely underestimated the possibility of just how much of a positive effect telling the story would have on science in general. The Science story came out the day after the New York Times Harvey Weinstein article. I remember Samantha Bee reporting on the Weinstein story. “Is there any place in the world that a woman can go to not be sexually harassed?” [she asked]. And then she said, “Antarctica? Nope,” and referenced the article on the show.

It’s hard to say that the Weinstein thing was positive, but the timing of it was serendipitous. Having something for people in the scientific community to point to, while everybody was talking about [Weinstein] was really, really important for keeping it close to home. I got a lot of emails saying, “I’m so sorry, this happened to you.” At times, just the sheer volume of emails and also the sadness of how many people told me their stories were overwhelming. Even now, years later, I’m still getting emails, asking for advice.

I’m not sure if I’d still worry about my daughter going into STEM or not. It does seem as if things are changing really slowly. There’s more of a cultural expectation that people would report harassment, without there being a similar change in what happens to people when someone is reported. So people are reporting more, but I don’t see that the consequences are really changing much.

The other thing that we saw with the MeToo movement is like, where’s the better job? I mean, it is bad in science. But it’s also bad in journalism. It’s bad in being an actress. I’m sure it’s bad being a meat packer. I’m not sure what to do—what anyone should do—except to try to make it better.