Michael Rubin agrees with me that George Bush didn’t do a bang-up job on the democracy promotion front, but thinks this shouldn’t be a partisan fight:

I do agree a bit with Drum, albeit without the snark, when he says, “George Bush’s main achievement in this arena wasn’t to promote democracy, it was to completely cement Arab cynicism about America’s obvious lack of concern for democracy.” The difference between me and Drum appears to be that I don’t think partisan animus toward a previous president should excuse the abandonment of transformative diplomacy. Give Bush credit: He broke with the past and made democratization central to the debate. Cynicism toward democratization existed long before Bush was president when, in the context of the Cold War and after, Washington proved itself willing to coddle dictatorships. It is infuriating, however, that the gap between the rhetoric and reality of the Bush administration grew so large, and that in his second turn, Bush was willing to accept such backsliding in Lebanon, Egypt, and elsewhere.

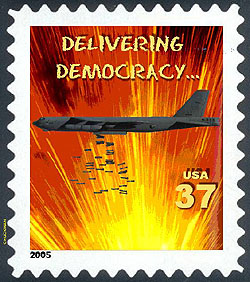

I don’t know enough about the literature on democracy promotion to say an awful lot about this, but I don’t agree that Bush “broke with the past and made democratization central to the debate.”  Rather, I think Bush and his team of old school anticommunists merely revived the Cold War context Rubin talks about, where democracy was less a real goal than it was a rhetorical cudgel to use against countries we didn’t like. In the postwar era, that mostly meant working to overthrow left-wing dictatorships while leaving the right-wing variety alone (famously given an intellectual foundation by Jeanne Kirkpatrick in “Dictatorships and Double Standards”). In the Bush era, this transitioned with barely a pause into working to overthrow Middle East dictatorships we didn’t like while giving a pass to the ones that supported us.

Rather, I think Bush and his team of old school anticommunists merely revived the Cold War context Rubin talks about, where democracy was less a real goal than it was a rhetorical cudgel to use against countries we didn’t like. In the postwar era, that mostly meant working to overthrow left-wing dictatorships while leaving the right-wing variety alone (famously given an intellectual foundation by Jeanne Kirkpatrick in “Dictatorships and Double Standards”). In the Bush era, this transitioned with barely a pause into working to overthrow Middle East dictatorships we didn’t like while giving a pass to the ones that supported us.

That just doesn’t seem transformative to me. It never has. In fact, Bush always struck me as less serious about democracy than his predecessors. To him it was a nice slogan — every American politician is in favor of democracy, after all — but anyone who’s serious about democracy knows that it’s not the kind of thing you can get overnight. It depends critically on education, on institutions, on culture, on overcoming corruption, on property rights, on the rule of law, and a dozen other things. None of these were things that Bush ever seemed to have the patience to bother dealing with.

Obama, conversely, seems to have a better handle on this, both temperamentally and intellectually. The result might be less bombastic and emotionally satisfying, but it’s a more effective way of actually accomplishing something. Less transformative rhetorically, perhaps, but if he follows through it’s likely to be much more genuinely transformative in practice.

I’m still being partisan here, but I’m not sure that can be helped. The approaches of Bush and Obama aren’t just personal, after all, but reflect different world views. The Bill Kristol wing of the conservative movement believes pretty strongly in a big bang approach to democratization, something that I just don’t see any future in. The Obama wing of liberalism, conversely, seems to see democracy promotion as small ball: lots of hard slogging, lots of public diplomacy, and lots of minor initiatives that fly under the radar and don’t produce dramatic moments to rally around.

Unfortunately, that approach seems to elicit little but scorn from conservatives. Like Rubin, I’d like this whole arena to be less partisan, but I’m not sure that’s possible. At least, not judging from the first few months of the Obama administration, anyway. It’s too bad.