The title of this post is mostly whimsy: in his speech about financial reform today, Ben Bernanke barely even mentioned leverage as a problem. In fact, his only use of the word (in the financial sense, anyway) came toward the end when he vaguely suggested that a new government agency might be set up to, among other things, assess the potential for “broad-based increases in financial leverage…to increase systemic risks.”

Since I think massive abuse of leverage is at the heart of what turned an ordinary asset bubble into a global meltdown, I’m disappointed that he didn’t spend more time on this. But on a related matter, he did say this:

Since I think massive abuse of leverage is at the heart of what turned an ordinary asset bubble into a global meltdown, I’m disappointed that he didn’t spend more time on this. But on a related matter, he did say this:

However, there is some evidence that capital standards, accounting rules, and other regulations have made the financial sector excessively procyclical — that is, they lead financial institutions to ease credit in booms and tighten credit in downturns more than is justified by changes in the creditworthiness of borrowers, thereby intensifying cyclical changes.

For example, capital regulations require that banks’ capital ratios meet or exceed fixed minimum standards for the bank to be considered safe and sound by regulators. Because banks typically find raising capital to be difficult in economic downturns or periods of financial stress, their best means of boosting their regulatory capital ratios during difficult periods may be to reduce new lending, perhaps more so than is justified by the credit environment. We should review capital regulations to ensure that they are appropriately forward-looking, and that capital is allowed to serve its intended role as a buffer — one built up during good times and drawn down during bad times in a manner consistent with safety and soundness.

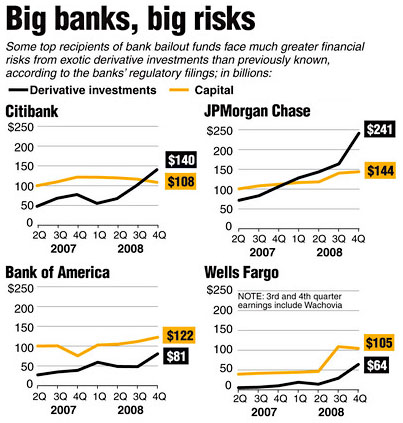

Capital ratios basically regulate the amount of leverage a bank is allowed to take on, and what Bernanke is suggesting here is that in good times, when animal spirits are high and anyone with a pulse is offered a no-down loan, capital ratios should be increased, thus reducing bank lending and keeping leverage within reasonable bounds. In bad times, when animal spirits are moribund and deleveraging shuts down the credit pipeline, capital ratios should be decreased, allowing banks to loan more money.

This has always struck me as a good idea. But Bernanke doesn’t say how he thinks it should be done. Would a board of some kind make these decisions twice a quarter, the way the Fed does with interest rates? Or would there be some kind of automatic mechanism involved? If the former, what confidence do we have that they’d really be willing to take the punch bowl away during boom times? The Fed sure wasn’t willing to do so during the 2002-07 expansion. Overall, this is a good suggestion, but it could bear some fleshing out.