In the seemingly endless healthcare reform debate, it seems like every day brings yet another proposal for a compromise on a public option. Today brings word of one that might actually be a workable idea: a national plan, created by Congress and standardized for the entire country, but that allows states to opt out if they don’t want to participate. Ezra Klein:

In the seemingly endless healthcare reform debate, it seems like every day brings yet another proposal for a compromise on a public option. Today brings word of one that might actually be a workable idea: a national plan, created by Congress and standardized for the entire country, but that allows states to opt out if they don’t want to participate. Ezra Klein:

That’s a real improvement over Tom Carper’s proposal allowing individual states to create their own public options, which would would be quite a bit weaker than a national program. It also creates a neat policy experiment: We can see, over time, what happens to state insurance markets that include the national public option and compare them with those that don’t. We can see whether the worst fears of conservatives are realized and private insurers are driven out and providers are forced out of business due to low payment rates, and we can see whether the hopes of liberals are right and costs come down and private insurers become leaner and more efficient. Or both, or neither. It’s an opportunity to pit liberal and conservative policies against each other, rather than just pitting liberal and conservative congressmen against each other.

Not bad. Let’s put those laboratories of democracy to work! I’d add that this would also be an interesting political experiment. The states that would benefit most from access to a public option are those in which there are the fewest private insurers. However, those are also the states in which the insurers have the most political power and can lobby the most effectively to keep the public option out. So which of these is the more powerful force? I, for one, would be interested to find out.

been to coopt and bribe all the major players, says this is not just a legislative strategy, but also a strategy for

been to coopt and bribe all the major players, says this is not just a legislative strategy, but also a strategy for  Betsy McCaughey’s mendacious article

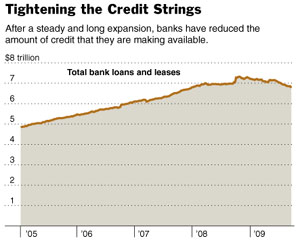

Betsy McCaughey’s mendacious article  And if banks can’t bundle up their loans, securitize them, and sell them off, they just won’t make any loans. “As long as the market remains closed,” says the piece, “banks will be reluctant to make loans for commercial real estate, since they would have to hold on to them, rather than package them into securities.”

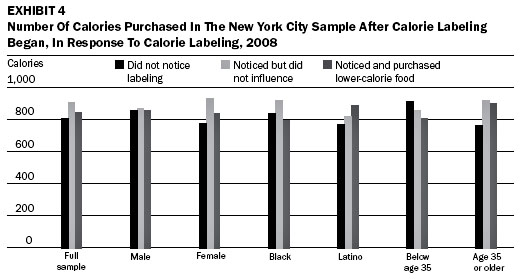

And if banks can’t bundle up their loans, securitize them, and sell them off, they just won’t make any loans. “As long as the market remains closed,” says the piece, “banks will be reluctant to make loans for commercial real estate, since they would have to hold on to them, rather than package them into securities.”  and if they’d changed their selection because of it. Then they got receipts from each respondent so they could find out what they’d actually purchased.

and if they’d changed their selection because of it. Then they got receipts from each respondent so they could find out what they’d actually purchased.

I’ve written a bit lately about how banks make a lot of money by exploiting complexity and confusion. This works all the way from the small (overdraft fees) to the huge (weird credit derivatives that no one really understands). Apparently the healthcare industry, which was never exactly a model of straight talk and plain speaking in the first place, is taking lessons. No longer content to simply bill for procedures,

I’ve written a bit lately about how banks make a lot of money by exploiting complexity and confusion. This works all the way from the small (overdraft fees) to the huge (weird credit derivatives that no one really understands). Apparently the healthcare industry, which was never exactly a model of straight talk and plain speaking in the first place, is taking lessons. No longer content to simply bill for procedures,  But it turns out this is really hard to document. Surprisingly hard. There’s plenty of outrageousness to choose from, but most of it is either too dry (numbers, numbers, numbers), too complex to hit you in the gut (derivatives, Fed policy, etc.), too distant from the real center of action, or too hidden to really get at effectively. Moore, it turns out, had the same problem.

But it turns out this is really hard to document. Surprisingly hard. There’s plenty of outrageousness to choose from, but most of it is either too dry (numbers, numbers, numbers), too complex to hit you in the gut (derivatives, Fed policy, etc.), too distant from the real center of action, or too hidden to really get at effectively. Moore, it turns out, had the same problem.