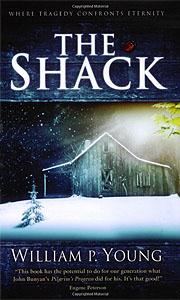

From Nathan Heller, explaining William Paul Young’s mega-bestselling religious allegory, The Shack:

From Nathan Heller, explaining William Paul Young’s mega-bestselling religious allegory, The Shack:

Theologically speaking, there is something for everybody in The Shack, but mostly in the sense that there is something for everybody in a meatloaf.

After writing about The Shack a couple of months ago, I finally got around to reading it recently. And as Heller suggests, it’s about a lot of things: sort of a weird stew of conventional Christian theology mixed with lots of new-agey spiritualism whose goal is to reconnect you with Christ. Among other things, Young rattles on about the Trinity, the nature of time, what it’s like in heaven, the power of redemption, and a hundred other things. At its heart, though, The Shack is concerned with perhaps Christianity’s most intractable question: why does an omnipotent God permit the existence of evil? In other words, it’s a meditation on theodicy.

And to give Young credit, he doesn’t shy away from asking God to account for a case of serious evil: a ten-year-old girl named Missy who’s kidnapped, possibly sexually assaulted, and then murdered in a remote shack by a sadistic serial killer. Her father, Mack, quite understandably has his already tenuous faith shaken by the fact that a loving God could allow this to happen, so a couple of years after the murder God invites him to spend a weekend in the shack (along with Jesus and the Holy Ghost) where everything will be explained. 200 pages later, here’s the payoff:

“Could I have prevented what happened to Missy? The answer is yes.”

Mack looked at Papa [i.e., God], his eyes asking the question that didn’t need voicing. Papa continued, “First, by not creating at all, these questions would be moot. Or second, I could have chosen to actively interfere in her circumstance. The first was never a consideration, and the latter was not an option for purposes that you cannot possibly understand now. At this point, all I have to offer as an answer are my love and goodness, and my relationship with you.”

Italics mine. This is, needless to say, not exactly a cutting-edge contribution to the theodicy literature. In the end, God doesn’t really have any answers at all for Mack, at least not in the usual sense of “answer.” However, it does turn out that God and Jesus are really extremely charismatic folks, and that’s enough. Mack finishes up the weekend feeling much better about things because he finally trusts God.1

I suppose it says something that this is enough to sell 7 million copies (or whatever it’s up to now). I’m not sure what, but something. Here’s Heller’s crack at it: “[Young’s] theories — how to believe in Adam while supporting particle-physics research; why the Lord is OK with your preference for lewd funk more than staid church music — accomplish what mainstream faiths tend to fail at: connecting recondite doctrine to the tastes, rhythms, and mores of modern life. The Shack’s wild success doesn’t reveal how Bible-thumpy this country is. It shows how alienated from religion we’ve become. And though the novel, as a novel, is a sinner’s distance from perfection, it’s an eloquent reminder that, for those who give some faith and effort to the writing craft, there is, even today, the chance to touch and heal enough strangers to work a little miracle.” Maybe so.

1Plus God gives him a glimpse of Missy in heaven, and she’s pretty happy there. So that helps too.