Felix Salmon ponders the political brawl surrounding the Fed’s quantitative easing program:

For reasons I don’t fully understand, the debate over QE2 has divided along party-political lines, with the Republicans lining up against it and the Democrats attacking them….Interestingly, this is one of those old-fashioned technocrat vs technocrat policy debates, in contrast to the technocrat vs populist debates which seem to have taken over far too much airtime of late. But it’s just as shrill.

….Bernanke, then, has every reason to want to reduce the volume on this debate: the mere existence of the debate itself can easily counteract any good which comes from QE2. One way of doing that would be to admit that QE2 is an untried experiment: while QE1 worked as a weapon in the crisis-fighting arsenal, QE2 is being asked to do something quite different. So the Fed should define much more clearly than it has done until now what exactly QE2 is designed to achieve, and what criteria might be used to determine whether it is succeeding or failing. And if it’s showing signs of failing, then the Fed should also be explicit about how and when it might be unwound.

I’m not a monetary economist, and the technical arguments about the mechanics of QE2 and what it will accomplish are impossible for me to evaluate properly. However, one thing does seem to be fairly clear: despite the scary sounding $600  billion number, the actual impact of QE2 is almost certain to be fairly small. With interest rates already so low, there’s simply not enough money involved to move markets substantially.

billion number, the actual impact of QE2 is almost certain to be fairly small. With interest rates already so low, there’s simply not enough money involved to move markets substantially.

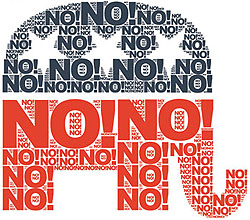

In other words, regardless of whether you think QE2 is good policy, it’s next to impossible to understand the increasingly hysterical Republican reaction to it. Unless, of course, you consider the context: Republicans aren’t just mounting a campaign against the Fed. They’re equally dedicated to championing a damaging economic argument about regulatory uncertainty that doesn’t withstand a moment’s scrutiny; they’ve already rejected several compromise opportunities to extend the Bush tax cuts unless a permanent extension of the high-end cuts was included; and they’re apparently planning to play a high-stakes game of chicken over raising the debt ceiling in a few months.

None of these things bespeaks a genuine concern with the economy. Instead, they suggest a party that’s simply jockeying for political advantage and figures that maximum chaos is in its best interest. It also explains why QE2 has divided along party-political lines: it hasn’t. Only Republicans are wholeheartedly on one side. Democratic reaction has been both varied and fairly subdued.

QE2 is vanishingly unlikely to either succeed or fail strongly enough for either side to make a bulletproof argument about whether it worked, and in any case benchmarks aren’t really what Republicans are after. They just want the economic argument to be focused solely on taxes, taxes, and taxes. The more noise the Drudge/Rush/Fox axis can generate over everything else — in other words, the more they can argue that nothing else works — the better their tax argument looks.