Our story so far: one of the funding mechanisms for healthcare reform is an excise tax on expensive health plans, popularly known as the “Cadillac tax.” As policy, it’s a good idea: by taxing expensive plans, you provide an incentive to keep their costs down. As politics, though, it sucks: union health plans, which are often pretty rich, would get hit by the tax. And Democrats like unions.

So yesterday everyone compromised. The excise tax is still in the bill, but the cutoff for the tax was raised from $23,000 to $24,000, dental and vision were excluded, and implementation was delayed a couple of years to give unions more time to renegotiate their contracts. In other words, a policy beloved mostly by wonks and deficit hawks stayed largely intact and unions got only a few crumbs. Nonetheless, John Boehner (R–Ohio) thundered that it  was the “latest in a long line of backroom payoffs and sweetheart deals.” Sarah Palin tweeted that workers “should oppose their UnionBOSSES backroom deal.” Even some liberals bought the framing: “I’m not about to pretend that the union deal was anything but interest group politics,” said Ezra Klein.

was the “latest in a long line of backroom payoffs and sweetheart deals.” Sarah Palin tweeted that workers “should oppose their UnionBOSSES backroom deal.” Even some liberals bought the framing: “I’m not about to pretend that the union deal was anything but interest group politics,” said Ezra Klein.

But except for the sense in which everything in a democracy is interest group politics in one way or another, I don’t buy it. This compromise doesn’t give unions anything. All it does is slightly moderate a basically anti-union tax. If Democrats were really cutting backroom deals with union bosses, they never would have proposed the excise tax in the first place. Or they would have exempted union contracts completely. There are plenty of other ways to fund healthcare reform, after all. But we’ve gotten to a point in the United States where anti-union sentiment is so widespread that (a) proposing a tax that falls largely on unions, and then (b) reducing it a bit, is considered a grubby giveaway even by some lefties. Yeesh.

And I say that as a supporter of the excise tax, which I think is good policy even if it does harm union interests a bit.1 But whatever else you can say about it, it does harm union interests, and the new version continues to harm union interests. It just harms them a little less. I sure wish we could cut a few “backroom” deals like that when it comes to giveaways for the rich and powerful.

1Though, as Ezra points out here, there are better, more progressive alternatives.

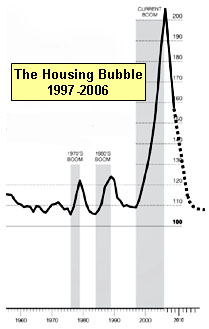

Housing wasn’t the only financially induced

Housing wasn’t the only financially induced  Even if they had put housing price implosion in their models, where would they have gotten the data to fine-tune their models? It’s not enough to say, “We should model a broad national decline in house prices;” you need some values for how many people will default when house prices fall. [Etc.]

Even if they had put housing price implosion in their models, where would they have gotten the data to fine-tune their models? It’s not enough to say, “We should model a broad national decline in house prices;” you need some values for how many people will default when house prices fall. [Etc.] I could sit here and be really cynical. I’ll hold off on the cynicism for a couple hours, I’ll hold off on it. I’m going to hold off on it, give the show’s flow a chance to establish, ’cause it’s going to be the Media Tweak of the Day.

I could sit here and be really cynical. I’ll hold off on the cynicism for a couple hours, I’ll hold off on it. I’m going to hold off on it, give the show’s flow a chance to establish, ’cause it’s going to be the Media Tweak of the Day. That’s been true in countries such as the Netherlands and Switzerland, and in Singapore, which is often upheld as a conservative model, contributions to health savings accounts are compulsory. Eliminate those options from the U.S. menu, and you’re ensuring that Medicare, Medicaid or some sort of public option will eventually take over the market, as there’s no constitutional issue with taxation in return for public services.

That’s been true in countries such as the Netherlands and Switzerland, and in Singapore, which is often upheld as a conservative model, contributions to health savings accounts are compulsory. Eliminate those options from the U.S. menu, and you’re ensuring that Medicare, Medicaid or some sort of public option will eventually take over the market, as there’s no constitutional issue with taxation in return for public services. My

My  Fannie-Freddie are even worse; the participants claimed that they had a 95-to-1 leverage at one point (just 18 basis points of capital), a monstrously risky number for any firm, much less a large one.

Fannie-Freddie are even worse; the participants claimed that they had a 95-to-1 leverage at one point (just 18 basis points of capital), a monstrously risky number for any firm, much less a large one.