Several years ago I published a series of blog posts from Jonathan Dworkin, a medical student at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. He spent a year organizing a collaboration between Kurdish and American doctors in order to assess the long-term consequences of Baathist chemical attacks on the Kurdish civilian population of Halabja, and in 2006 he spent several months travelling in Iraqi Kurdistan and sending occasional dispatches about his travels. You can find them here (scroll to the bottom for a complete list).

Jonathan is now an infectious diseases fellow at Brown, and has spent the past few weeks in Kurdistan working to develop the public health infrastructure. He’s back now, and has written a series of three posts on how things have changed since his first visit, hitting on themes of transparency in the economic system, willingness of the government to peacefully transfer power, freedom of journalists, independence of public institutions (like the university), and relations between Kurds and Arabs. Kurdistan has pretty much fallen off the radar of the U.S. media, so this is stuff you won’t find anywhere else.

Part 1 is below. The next two parts will follow on Thursday and Friday.

“Basis of life is sleep, sex, nutrition. I am nutrition.” That’s what the cook said, and then he handed me a meatball. Kurdistan has changed a lot in five years, but the cook at the dar is an example of how it hasn’t changed, and hopefully never will change. After spending two days in a hotel I moved to the residence for medical house officers, which everyone here calls the dar. This is one of Kurdistan’s  primary mechanisms for alleviating the economic hardship of prolonged training and the social hardship of deferred marriage. The dar is a place for young doctors to live together, study together, and tease one another. And in a characteristically class levelling way, the teaser in chief of this dar is the cook. “Doctor is survivor of electro-shock therapy,” he explained while puffing on a cigarette and indicating the young psychiatrist sitting to my right. “He is very crazy man. He will sleep next to you tonight.”

primary mechanisms for alleviating the economic hardship of prolonged training and the social hardship of deferred marriage. The dar is a place for young doctors to live together, study together, and tease one another. And in a characteristically class levelling way, the teaser in chief of this dar is the cook. “Doctor is survivor of electro-shock therapy,” he explained while puffing on a cigarette and indicating the young psychiatrist sitting to my right. “He is very crazy man. He will sleep next to you tonight.”

The ostensible reason I’m in this situation is to conduct public health research for Brown University. The research is part of my training as an infectious diseases doctor. During my previous visit to the Kurdish autonomous region of Northern Iraq in 2006 I saw several cases of typhoid fever, but our small team wasn’t equipped to characterize them in any systematic way. This time we are armed with data collection tools and grant funding. Burden of disease studies — a simple form of public health work — are often precursors to interventions such as vaccine programs or infrastructure investments. But all of this is largely beside the point. The real reason I’m back, doing this typhoid project in this province, as opposed to another, is because I love Kurdistan. In medicine it’s the people that draw you in, and the work is an expression of solidarity.

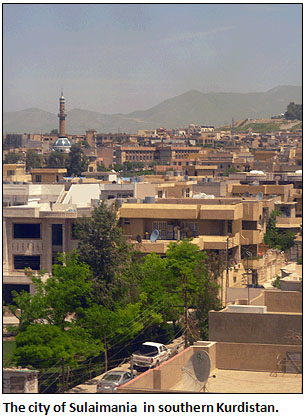

The dark side of this trip begins with the fact that it almost didn’t happen. In February, during the beginning of the Arab spring, protests erupted in Kurdish Sulaimania. The reasons for the opposition were varied, but at its core the protests were against the patronage system established by the ruling Kurdish parties. For two months the opposition occupied Sara Square, in the center of the city, and the protests ended when the authorities deployed Kurdish units of the Iraqi Army. Hundreds were wounded and several people died in the worst internal violence since the 1990s.

The original plan for my trip was to come with my family and live for a month in an apartment my friends had picked for me. The apartment was in a comfortable neighbourhood called German Village. After the protests erupted unidentified gunmen stormed the area and burned down an opposition television station. Nothing will ruin the reputation of a nice neighbourhood faster than a secretive militia affiliated with a political party. The German Village becoming more like Beirut, I changed my plans and arrived alone.

Now the streets are quiet. German Village is well-kept and calm, deceptively German. There is no heavy security presence in Sara Square, though party buildings are well defended. The economic and cultural life of the town appears uninterrupted, at least on the surface. In fact the city is larger and more vibrant than five years ago. Electricity is better. Water quality, though imperfect, is better. Construction projects and new businesses are everywhere. The hospital is functioning on a much higher level. Not only are routine diagnostic tests available 24 hours per day, but advanced interventions such as cardiac bypass surgery and kidney transplantation are now offered. One of the ironies of recent history here is that the government’s moment of crisis ought to be a moment of triumph. The Kurdish region never descended into violence, despite what happened in the rest of Iraq. There was a contested election, opposition parties, and a critical press. All of that success is threatened by the recent violence.

Spending a weekend with my friends before beginning data collection, it’s easy to pretend this is the Sulaimania of five years ago. You can still walk the streets safely and encounter friendly smiles as an American. You can still go to a cafe and talk politics over rice, vegetables, and grilled meat. There’s an openness one feels around Kurdish people, particularly in Sulaimania, that reminds me of why I fell in love with this town in the first place. But probe deeper and you find a poisonous pessimism that is taking root. It is that despair, and the realization that a bold attempt to build a new Kurdish civic society may end in failure, that is the real story this spring in Sulaimania.