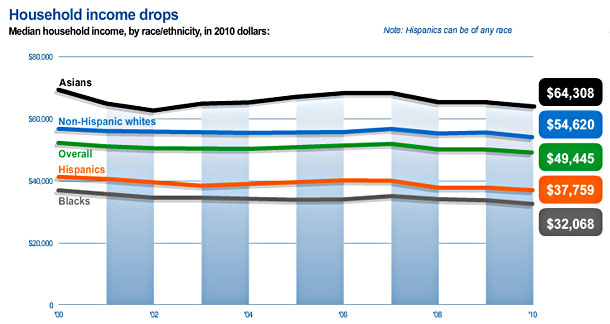

Matt Yglesias likes this chart from USA Today that illustrates what has happened to household incomes over the past decade:

In fairness, you really do need to account for rising health insurance premiums before you conclude that average incomes have dropped. I’ll spare you the details, but the census data shows that overall median incomes, adjusted for inflation, have dropped $3,719 over the past decade. However, the employer share of healthcare premiums has gone up almost exactly the same amount. Toss that back in, and total household compensation (cash plus health insurance) has been pretty much flat.

Still, that’s pretty bad:

This, I think, does a great job of illustrating the fact that the asset price collapse –> recession –> lost decade cycle is really something that started 10 years ago rather than a forward-looking risk. It’s often said that the 2001 recession was “brief” and “mild,” but the employment and income situation kept deteriorating for years and neither the employment-population ratio nor wages ever re-obtained their previous peak. The longer we go on not effectively addressing the additional labor market trauma of 2008-2009, the more this all merges into one giant pool of long-run economic dysfunction.

I keep meaning to write more about this, and I promise that someday I will. But there’s a real phenomenon here that hasn’t gotten enough attention. We often point to 1973 as an inflection point for workers: Before that, median incomes rose right along with economic growth, but starting that year income growth suddenly slowed dramatically. Instead of rising 2 to 3 percent a year, household income rose less than 1 percent per year.

It now looks to me like 2000 was another inflection point. Household incomes went from 1 percent growth to zero growth, and they’ve been stuck there ever since. Even researchers who are skeptical that income inequality rose dramatically after 1973 mostly accept that it’s definitely risen since 2000. The entire past decade has been an economic disaster on multiple fronts, and that’s one of the reasons the financial collapse of 2008 has been so terrible. We had a decade’s worth of labor market weakness that was partly masked by a housing bubble, and it all came crashing down within a year or two. Instead of a long, slow slide, we got ten years worth of drops compressed into 24 months. For more on this, see Scott Winship here.

And I really will try to write more about this eventually. It’s important. Unfortunately, the reasons are still hazy and there are dozens of theories about what’s happening. But something sure is.