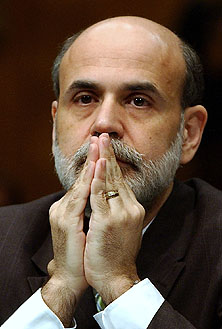

Roger Lowenstein has a profile of Ben Bernanke in the latest issue of the Atlantic. It’s called “The Villain.” On the cover, though, it’s called “The Hero.” Ironic! “The left hates him,” says the subhead. “The right hates him even more. But Ben Bernanke saved the economy—and has navigated masterfully through the most trying of times.”

It’s kind of weird, though. Lowenstein provides loads of evidence that the right hates Bernanke, but he doesn’t actually come up with much evidence that we lefties hate him too. In fact, he’s only got two things. First, some guy in Lowenstein’s neighborhood has an “End the Fed” bumper sticker on his car. No, I don’t get what that’s supposed to prove either. Second, Paul Krugman has said some critical things about Bernanke on occasion. I’m actually kind of curious to know what Krugman thinks  of this. Lowenstein insists that Krugman been “scathingly critical” of Bernanke, but my take is that he’s been more like mildly disappointed. Phrases like “shameful passivity” and “wimps out” are just shots across the bow by Krugman’s standards. When he’s truly being scathingly critical, there’s really no mistaking it.

of this. Lowenstein insists that Krugman been “scathingly critical” of Bernanke, but my take is that he’s been more like mildly disappointed. Phrases like “shameful passivity” and “wimps out” are just shots across the bow by Krugman’s standards. When he’s truly being scathingly critical, there’s really no mistaking it.

There are folks on the left who are scathingly critical of Bernanke, of course. But you don’t find them on the pages of the New York Times or the hallways of Capitol Hill. You find them on blogs. It’s just not the same as it is on the right, where presidential candidates, members of Congress, and major pundits and talking heads slag him routinely.

But enough of that. Let’s criticize Bernanke from the left and make Lowenstein’s article more accurate for him. We lefties all tend to think that the Fed ought to temporarily target a higher inflation rate while the economy remains weak, but Lowenstein explains why Bernanke doesn’t agree:

One obstacle is practical. Fed policy works, in part, by getting the market to do the Fed’s work (if the Fed is buying bonds, traders who want to be on the same side of the markets as the central bank will buy bonds too). But any policy adopted by less than a 7-to-3 majority by the Fed’s Open Market Committee would not be viewed by markets as a credible policy, likely to endure, and Bernanke is not guaranteed to get this margin today. “No central banker would do it,” Mankiw says of raising the inflation target; the political reaction would be too severe.

….This might seem to support Krugman’s thesis that Bernanke would like to boost inflation but has chickened out. But after talking with the chairman at length (he was generally not willing to be quoted on this issue), I think that, although Bernanke appreciates the intellectual argument in favor of raising inflation, he finds more compelling reasons for not doing so. First is the fear that inflation, once raised, could not be contained….Second, raising inflation is not always so easy….As Bernanke is well aware, this problem has generated an extensive literature, the gist of which is that the Fed would have to promise to be, in effect, “irresponsible.” In other words, the Fed would have to say, “Even when prices start rising, even when inflation starts to get out of hand, we will still keep rates near zero.” That is what sparked the inflation of the ’70s: people thought inflation was permanent, and a borrow-and-spend mentality set in. If Bernanke were to re-create that climate, it would be hard to shut down.

In other words, we still don’t know why Bernanke doesn’t support a higher inflation target. We don’t really even know if Bernanke supports a higher inflation rate. Lowenstein’s second point is that higher inflation can only happen if the Fed makes a credible commitment to it, and his first point is that the Fed currently has too many inflation hawks for anyone to believe a Fed commitment even if it made one. This says nothing about Bernanke’s personal views. It just says that right now he can’t do it. But would he if he could? Lowenstein says his “sense” is that “Bernanke is too much a sober central banker to want to risk the Fed’s credibility on inflation,” and I guess that’s a no. Or a maybe.

There are some other odd bits in the piece. I’m not really sure Lowenstein is right about the 70s, for example. Maybe some economists want to weigh in on that. And I was surprised to hear that “no one knows” whether raising interest rates on reserves can keep the money supply in check. I’ve always been under the impression that this is one of the bluntest tools in the Fed’s arsenal. The question isn’t so much whether it would work, it’s making sure you don’t put too much gunpowder in the bazooka. Maybe some economists want to weigh in on that too.

And what’s my take on Bernanke? I think he did a pretty good job in his first term, but I’m not sure he’s been anything special in his second — though I can’t say for sure whether anyone else could have overcome the Fed’s ideological inertia any better. In any case, a monetary specialist was just what we needed in 2007-09, but I would have preferred someone a little more dedicated to financial regulation for 2010-14.