Among the several ways that recession in Europe could hurt the global economy is via the specter of bank deleveraging. As you may recall, one of the proximate causes of the Great Panic of 2008 was the fact that American banks had run up huge amounts of leverage, something that makes the banking system extremely vulnerable to sudden shocks — like, say, a housing bubble bursting.

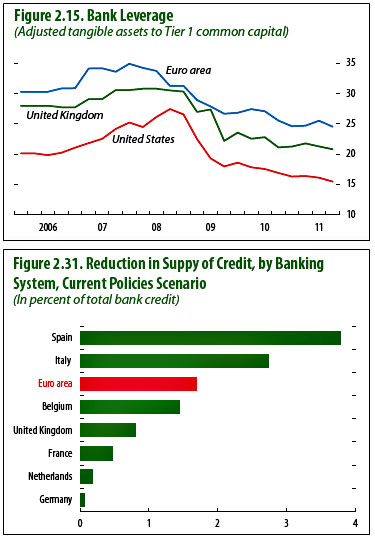

Well, European banks were even more leveraged than American banks. The top chart on the right, courtesy of a new IMF report, shows that American bank leverage peaked in 2008 at a ratio of about 25:1, and since then has dropped to a much  more sustainable 15:1. European banks, even after four years of deleveraging, are still at 25:1. This means they remain vulnerable to sudden shocks — like, say, Spain going bust — so they’ll need to continue deleveraging for several more years.

more sustainable 15:1. European banks, even after four years of deleveraging, are still at 25:1. This means they remain vulnerable to sudden shocks — like, say, Spain going bust — so they’ll need to continue deleveraging for several more years.

There are basically two ways they can do this. First, they can raise money by selling off assets. This is OK unless it turns into a fire sale, which is always a possibility. Second, they can reduce the amount of credit they make available. The bottom chart on the right shows the IMF’s estimate of credit contraction over the next couple of years.

The good news for Americans is that this probably won’t affect us directly very much: Most of the credit contraction will happen in Europe, and American corporations have deep access to capital markets to replace whatever they lose from European banks. There is, however, a potential indirect effect via derivative exposure, and also some more general exposure at a macro level if bank deleveraging keeps Europe’s economy in a rut.

Still, the IMF doesn’t think the credit contraction in Europe is likely to be all that severe: “The implied decline in the credit-to-GDP ratio [] sits between the relatively moderate experience in Japan in the 1990s and the more pronounced credit contraction in the United States in the earlier part of the financial crisis.” As long as European banks avoid a “synchronised and large-scale deleveraging” — i.e., a fire sale of assets — things will likely stay under control.

In other words, the big danger remains not sluggish growth in Europe, which everyone has already priced in, but the possibility of panic. And with sovereign debt still extremely wobbly in the south, monetary policy still too tight, austerity still the order of the day, and bank leverage still high — with all that still in front of us, panic remains a distinct option. A eurozone crackup is still a real possibility.