Last night Microsoft announced that it will take on Apple directly in the tablet market by designing and selling its own device. Farhad Manjoo is excited:

For the first time in its history, Microsoft is taking PC hardware as seriously as it does software. The software giant is coming around to a maxim that archrival Steve Jobs always held dear—that the best technologies come about from the tight integration of code and manufacturing, and that no company can afford to focus on just one half of that equation.

….During the last couple years, the software company has been working to make its next version of Windows perform amazingly well on touchscreen tablets….But after investing so much to create a great tablet interface, Microsoft risked losing the battle on hardware. Many of its traditional PC partners—Samsung, Asus, Dell, and HP—have already tried to take on Apple with rushed, ill-considered, cheaply made tablets. Microsoft would have been foolish to rely on that gang of losers  to create tablets that were worthy of the new Windows. With the Surface, the company is taking its future into its own hands.

to create tablets that were worthy of the new Windows. With the Surface, the company is taking its future into its own hands.

On two different levels, I don’t get this. First off, there doesn’t really appear to be anything all that special about the hardware Microsoft announced. It seems perfectly competent, and maybe even a little better than competent. But it’s basically a 10-inch tablet with a few ports, a kickstand to prop it up, and a nifty-looking integrated cover/keyboard. All in all, it’s a nice package but, as near as I can tell, nothing revolutionary. And nothing in Microsoft’s presentation suggested to me that Windows 8, the software that runs the Surface tablet, won’t work just as well on Samsung and Asus hardware as it does on theirs.

But that’s the least of my puzzlement. The main source is this: the most important aspect of the Surface tablet — by a mile — isn’t that Microsoft is paying a bit more attention to hardware. It’s the fact that the Pro version is both a tablet and a real computer. This is huge, and it’s huge whether you’re an Apple fan or a Windows fan.

Here’s the thing: I have an iPad. I like it! Millions of other people like it. But let’s be honest: it’s a toy. It doesn’t have a file system you can use. It doesn’t run real apps. It can’t exchange data with your Mac easily. It has a bunch of limitations on what you’re allowed to do with it. (You can’t upload files via a website, for example.) Put all this stuff together, and for most of us the iPad simply can’t replace our main computer. In fact, it doesn’t even play very well with our main computer.

In the Mac world, a tablet that actually ran Mac OS, made data exchange easy, and supported regular apps, would be great. But Apple doesn’t appear to have any plans for such a device, and this is what really sets the Surface tablet apart. If you live in the Windows world, as millions of us do, the Surface concept is very, very seductive. As a tablet, the Metro interface offers the casual ease of use that you want in a tablet. Toss in the keyboard/trackpad add-on, plug in a bigger display, and the Windows interface allows you to use it as your primary computer. Or, if not quite that, at least as a full-powered secondary computer. That’s huge.

Now, obviously, the devil is in the details, and there are lots of details Microsoft hasn’t yet addressed publicly. How much will the Surface tablet cost? What’s the battery life? Does Windows 8 suck? How about Bluetooth? GPS? 4G data support? Is Intel’s Ivy Bridge chipset any good? How fast is it? Etc.

The answers to these questions might very well be disappointing. See George Ou’s comment here for more on that. Put this all together, and I think it’s quite possible that Microsoft might very well fail in its newfound dedication to hardware — which I suspect is far more about profit margins than about a sudden appreciation for the “tight integration of code and manufacturing” in any case. But even if Microsoft does fail, other hardware manufacturers are almost certain to step in with devices that make the right set of tradeoffs and allow Windows 8 tablets to perform genuine double duty as casual plaything and serious computer. Whether it comes from Microsoft or Apple, that’s the future of the tablet.

to create tablets that were worthy of the new Windows. With the Surface, the company is taking its future into its own hands.

to create tablets that were worthy of the new Windows. With the Surface, the company is taking its future into its own hands. submit a pair of photos along with your passport application, and the only way to acquire these photos is by engaging in private commerce. Or take this,

submit a pair of photos along with your passport application, and the only way to acquire these photos is by engaging in private commerce. Or take this,

not much going on aside from campaign inanities. Summer has come early.

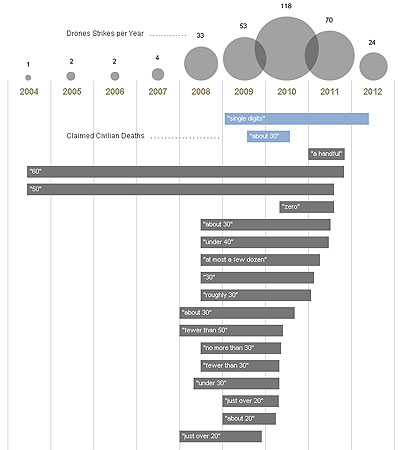

not much going on aside from campaign inanities. Summer has come early. authorization for military force” in the case of Iran.

authorization for military force” in the case of Iran.