A few days ago I wrote a post disputing the idea that President Obama made a mistake by pursuing healthcare reform in 2009 instead of focusing like a laser solely on the economy and pushing for more stimulus spending. In a nutshell, I don’t think Obama could have gotten a bigger stimulus bill in February, and with employment figures steadily improving throughout the year I don’t think Congress would have  passed a second stimulus bill in October. Sean Trende doesn’t agree, and provides three reasons I’m wrong:

passed a second stimulus bill in October. Sean Trende doesn’t agree, and provides three reasons I’m wrong:

- It was clear by August that the recession was deeper than anticipated.

- If the Congress could be persuaded to pass health care reform, it also could have passed a second stimulus.

- Obama might have gotten more by playing small ball. (This is, perversely, illustrated with a reference to the New Deal.)

These kinds of counterfactuals are impossible to prove conclusively either way, but I just don’t buy this one. Yes, by August we knew the recession was worse than we thought, but the fact remains that employment figures were ticking up in a promising way and the previous stimulus bill had been passed only six months earlier. I just don’t see any way that Ben Nelson and the other red-state Democrats would have been willing to pass a second stimulus of any significant size in late 2009.

I’m not impressed with #2 either. Healthcare reform has been a Democratic dream for nearly a century, and even at that Obama was only barely able to get his entire caucus to stick together and pass it. And that was for a pretty modest bill. A temporary stimulus bill just doesn’t have the same historical heft behind it.

Then there’s #3. This one is a little more interesting. Obama, says Trende, shouldn’t have passed a single big stimulus bill:

Instead, the president would have been much better off breaking the stimulus up into five or six pieces, spread out over his first 100 days. His presidency would have had a very different narrative attached to it if the first major piece of legislation passed by his administration had been $275 billion in tax cuts — or even better, two or three pieces of tax-cut legislation, grouped by subject — followed a week later by the unemployment compensation, followed a week later by the infrastructure spending, followed a week later by health care and education assistance, finished off with a miscellaneous bill.

For one thing, the headlines would have been dominated by the tax cuts, aid to the unemployed and to education, and so forth. Instead, there was a massive, amorphous “stimulus” with a $787 billion price tag for people to digest.

Quite frankly, Republicans would have supported at least some of the measures — in fact, the “mini-stimuli” approved throughout late 2009 and 2010 almost all passed with substantial Republican support. So it would have been with a “pure” tax-cut bill that kicked off the president’s term.

As it became clear that the downturn was worse than expected, additional rounds of tax cuts and spending legislation would have been easier to pass, since Obama likely would have maintained a higher approval rating (remember that it was the perception of massive spending, rather than the economy, that initially drove down his approval ratings).

This is….plausible. I think it’s a stretch, but it’s plausible. Still, I’m just not persuaded that there were any Republicans who would have repeatedly supported spending bills of any substantial size if only Obama had metered them out gradually instead of asking for one or two big packages. I find it far more likely that two or three of them would have gone along for a few months and then backed off. Ditto for the gang of centrist Democrats. And the Republican message wouldn’t have changed much either. Instead of “Obama is responsible for the biggest spending bill in history,” it would have been “Every month it’s another $100 billion. When does the out-of-control spending stop?”

Bottom line: there’s abundant evidence that Obama couldn’t have gotten a bigger stimulus bill in February than the one he got. And with the economy improving and hundreds of billions of dollars in stimulus spending still waiting to get into the pipeline, I simply don’t see any way that he could have rounded up 60 votes in the Senate for further stimulus in the fall. From the outside, it always seems possible that some small change in strategy might have saved the day, but that’s rarely the case in real life. And so it is here. I think it’s naive to believe that a little more cleverness about how the spending bills were spaced out would have changed anything very much. There only so much that cleverness can accomplish.

UPDATE: Noam Scheiber takes the other side of this argument, saying today that “of course health care reform made it harder for Obama to get more stimulus and speed up the recovery.” He makes some good points, but in the end I don’t find him a lot more persuasive than Sean Trende. It’s always easy to take the rosiest possible view of a strategy that wasn’t followed, but in real life an economy-centric strategy would have run into a lot of roadblocks that nobody is thinking about three years after the fact.

In the end, however, it turns out that I can live with Noam’s final conclusion: “We can debate the size of this effect—and I’m willing to believe it was second-order rather than first-order—but the existence of a tradeoff seems undeniable to me.” I’ll buy that, but honestly, I think it makes the case for focusing on healthcare rather than the opposite. If the effect of the healthcare focus was only second order, that means an economy-centric strategy would have produced only a modest amount of extra stimulus. But nobody thinks that a modest amount of extra stimulus would have had much impact on the actual state of the economy — and that’s what’s most important. The actual economy. Not messaging or small blips in Obama’s approval ratings. The actual economy. Another trillion dollars would have made a difference. Half a trillion dollars might have made a difference. But a couple hundred billion? That would have been a drop in the ocean.

passed a second stimulus bill in October. Sean Trende doesn’t agree, and provides

passed a second stimulus bill in October. Sean Trende doesn’t agree, and provides  of objectivity, won’t really call you on it, limiting themselves to fact checking pieces like Kessler’s buried on an inside page. And because virtually nobody except political junkies ever sees this stuff, it doesn’t hurt their campaigns at all.

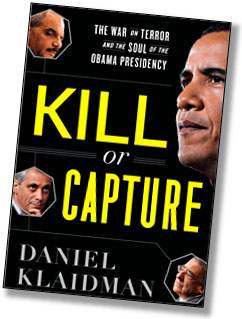

of objectivity, won’t really call you on it, limiting themselves to fact checking pieces like Kessler’s buried on an inside page. And because virtually nobody except political junkies ever sees this stuff, it doesn’t hurt their campaigns at all. who not only didn’t do any of that stuff, but became a drone-obsessed killing machine in the process?

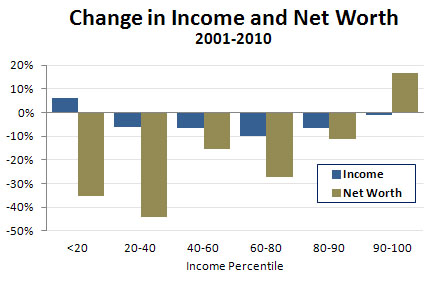

who not only didn’t do any of that stuff, but became a drone-obsessed killing machine in the process? The Federal Reserve published its

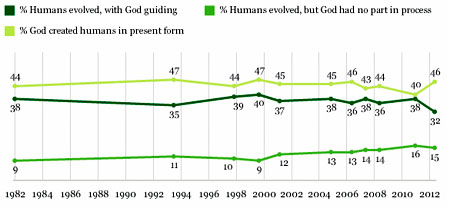

The Federal Reserve published its  about evolution, in which 46% of Americans say God created humans in their present form

about evolution, in which 46% of Americans say God created humans in their present form  anti-Obama story.) There is some variation in the Obama smack-downs, but all of the others hammer home the exact same arguments using the exact same verbiage; each is pretty much interchangeable with the other, and might well have been penned by a single source.

anti-Obama story.) There is some variation in the Obama smack-downs, but all of the others hammer home the exact same arguments using the exact same verbiage; each is pretty much interchangeable with the other, and might well have been penned by a single source.