Conservatives have made a big deal out of the fact that 38% of households with a union member voted for the union-busting Scott Walker in Tuesday’s election in Wisconsin. For example, here’s the New York Post:

Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s successful battle to keep his job during this week’s Wisconsin recall election got a lift from an unexpected quarter — voters from union households….“The union members, they’ll support us,” said presidential candidate Mitt Romney during a campaign stop in Texas. “Without the union members who support our campaign and support conservative principles — we wouldn’t have Scott Walker win in Wisconsin if that weren’t the case.”

Walker’s labor vote was a surprise for the first-term incumbent, given the outcry over his policies that wiped out collective-bargaining rights and automatic dues collection for public-employee unions. And that chunk of the union vote contributed to his comfortable 7 point win, 53-46, over Democrat Tom Barrett.

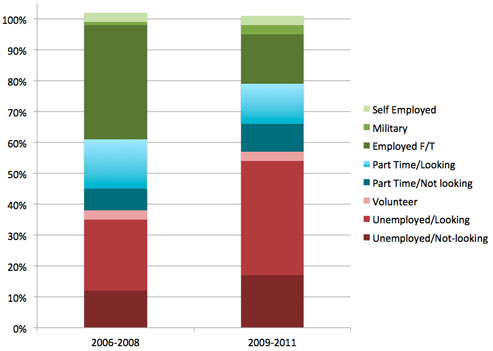

Actually, this is exactly the opposite of surprising. Take a look at past elections. In 2004, 38% of union members and 40% of voters in union households voted for George Bush. In 2008, 39% of union members and 38% of voters in union households voted for John McCain. In 2010, 37% of voters in union households nationwide voted for Republicans, and that’s also the share of the union vote that Walker got in Wisconsin that year.

For better or worse, about 37% of union members vote for Republicans, both nationwide and in Wisconsin. On Tuesday they did it again. So whatever lessons there are from Tuesday’s election, the idea that union members are somehow abandoning their own cause isn’t one of them. On that score, nothing interesting happened at all.

Ross Douthat puts last night’s results in Wisconsin

Ross Douthat puts last night’s results in Wisconsin

compared to LBJ. The second half of Caro’s book is about the first few months of Johnson’s presidency, and legislatively it’s primarily about how he won passage of two big bills: a major tax cut and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. So let’s go down the list of things LBJ did:

compared to LBJ. The second half of Caro’s book is about the first few months of Johnson’s presidency, and legislatively it’s primarily about how he won passage of two big bills: a major tax cut and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. So let’s go down the list of things LBJ did: much it. Today, Spero Tsindos of La Trobe University joins the fight in an editorial in the

much it. Today, Spero Tsindos of La Trobe University joins the fight in an editorial in the