The Pew Research Center has released the latest version of its American Values Survey, and the headline result is that although the values gap hasn’t changed much by age or gender or race or anything else, it has continued to increase  by political affiliation. The differences between Democrats and Republicans remained steady throughout the late 80s and 90s, but since 2000 have gone up from 11 percentage points to 18 percentage points. And the gap is continuing to grow.

by political affiliation. The differences between Democrats and Republicans remained steady throughout the late 80s and 90s, but since 2000 have gone up from 11 percentage points to 18 percentage points. And the gap is continuing to grow.

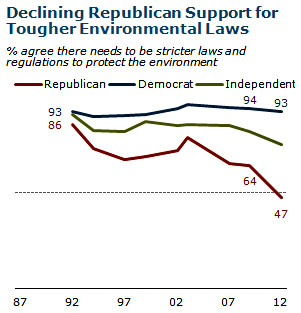

The most dramatic change is in environmental views. Take a look at the chart on the right. Back in 1987, there was hardly any daylight between Democrats and Republicans. Everyone agreed we needed strict environmental regs. But Republican support for environmental regulations dropped during the early 90s, and then, after ticking back up a bit, cratered completely during the Bush and Obama adminstrations, plummeting from 79% to 47% over the past decade. Some of this is probably due to the GOP’s general move toward the right during that time, but I’d guess that it’s mostly a response to global warming. Until 2003, the environment was a roughly bipartisan cause, but since then it’s become overwhelmingly identified with climate change, which in turn has become a violently political issue. We’d need more detailed polling to confirm what Pew seems to show here, but what it seems to suggest is that the partisan war over climate change has poisoned Republican support for environmental regulations more generally.

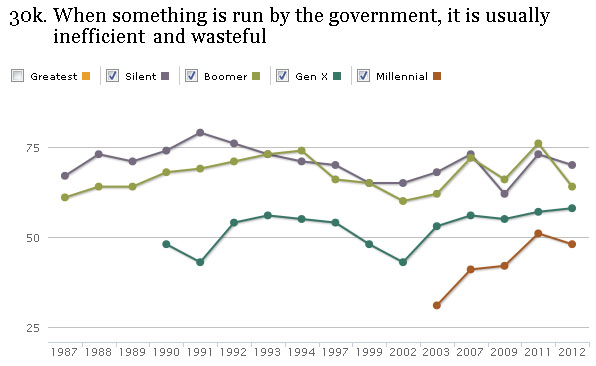

In related news, Pew has put up an interactive database that allows you to scroll through the questions they’ve been asking since 1987 and view the trends by age, gender, party, etc. There’s some interesting stuff there. For example, take a look at the question below, sorted by generation. Over the years, most of us have retained roughly the same view of whether the government is wasteful and inefficient. The postwar (“Silent”) and Boomer generations hover around 65% and Gen X hovers around 55% — with very little change as members of those generations get older. But Millennials are different. In 2003 they were pretty optimistic about government-run programs, with only about 30% saying they were wasteful. Today, though, nearly 50% think that. In the course of only a decade, they’ve become far, far more cynical about government programs.

Why? Is this related to the Iraq War? To the Bush/Rove administration more generally? To the stimulus bill? (The numbers went way up between 2009 and 2011.) Or were they just unnaturally optimistic during their 20s and are now catching up to everyone else? Any guesses?

van to repay a favor and a guy driving five strangers across town in a van in exchange for money he’s going to use to pay the rent.

van to repay a favor and a guy driving five strangers across town in a van in exchange for money he’s going to use to pay the rent. Steve Benen passes along a bit of raw data today about the

Steve Benen passes along a bit of raw data today about the