I wrote a quick post yesterday about the newly published criticism of Reinhart and Rogoff’s famous finding that countries with debt levels over 90 percent of GDP tend to grow very slowly. I played it for laughs as an Excel error, mostly because I’ve been around Excel long enough that it wouldn’t surprise me if someday we all end up dying in a thermonuclear war because of an Excel coding error. (This was a detail that WarGames got wrong.)

But of course, it’s a serious issue too. R&R famously found that countries with debt levels over 90 percent stagnated almost completely for years. Their growth rate was zero. This result was trotted out endlessly as intellectual backup for policies focused on reducing the deficit instead of fighting the recession and putting people back to work. But when R&R’s errors were corrected, it turned out that high-debt countries actually had growth rates of about 2 percent. That’s slow, but not catastrophic. Dean Baker makes an interesting point about this:

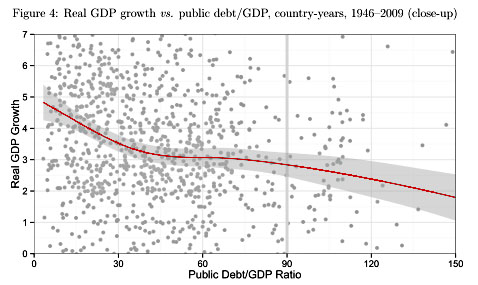

It is true that in most of their specifications HAP [the authors of the critical study] found growth was slower in periods with debt levels above 90 percent of GDP than below, but the gap was relatively small and nowhere close to statistically significant. Furthermore, they found a much bigger gap in growth rates around debt-to-GDP ratios of 30 percent. If we think that R&R’s methodology is telling us something important about the world then the take-away should be that we want to keep debt-to-GDP ratios below 30 percent.

The chart below, from the paper, shows this fairly dramatically. GDP growth falls steeply between debt levels of 0 and 30 percent, plateaus a bit, and then declines rather gently above 70 or 80 percent:

Needless to say, nobody argues that debt levels of 20 percent are dangerous. But if you take the R&R result seriously, why wouldn’t you?

Generally speaking, this is evidence that most interpretations of R&R get things backward. Causality doesn’t go from debt —> slow growth, but from slow growth —> debt. Countries that grow slowly tend to pile up debt faster. Debt is a symptom, not the disease itself.

On the other hand, I guess I wouldn’t throw out R&R’s results completely. Debt is a symptom, and although 90 percent isn’t some kind of magical barrier, it does suggest that maybe you’re doing something wrong. If you keep doing it wrong, investors might very well lose confidence and start demanding higher interest rates for your bonds, which could lead to a death spiral of sorts. The problem is that you never know just when this might happen. Maybe tomorrow, maybe ten years from now.

So growth is the answer. The question is how to get it. In the short term, more debt might be one piece of the puzzle.

UPDATE: UMass economist Arindrajit Dube dives deeper into R&R’s dataset here, and concludes, unsurprisingly, that it’s more consistent with the theory that low growth causes high debt than the other way around.