<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/shalf/3498754937/sizes/l/in/photostream/">shalf</a>/Flickr

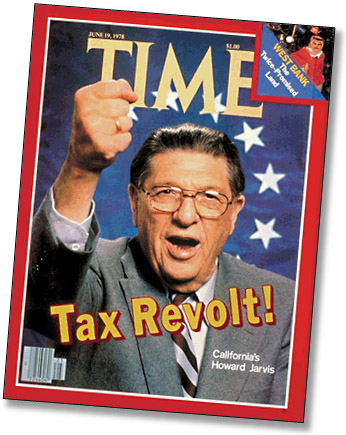

Yesterday was the 35th anniversary of the tax revolt in America. On June 6, 1978, two-thirds of Californians voted to pass Proposition 13, which cut and capped property taxes and mandated a two-thirds vote for any future tax increases. Howard Jarvis ended up on the cover of Time and the tax revolt was officially started.

Prop. 13 was certainly successful at its primary goal. Not only do I pay a property tax rate of 1 percent on my Orange County house, but I pay it based on the price of the house when I bought it 20 years ago, even though it’s doubled in value since then. My mother, who still lives in the house I grew up in, pays 1 percent of the value of her house as of 1978. That’s because Prop 13 not only caps the tax rate, it also caps the assessed value of property, which is allowed to go up no more than 2 percent per year.

For ordinary households, that’s the good news. But even if you’re a stone conservative, there’s some bad news to go along with that. For starters, Prop. 13 applies to corporations too, and corporations usually keep their property for a long time. That means their property taxes rarely reset, which in turn means that corporations pay a lower share of property taxes than they used to. What’s more, there are even clever loopholes that allow corporations to sell their property without resetting its assessed value, reducing their share of the tax burden even further.

What else? Well, Prop. 13 makes tax increases all but impossible, which means California has been overtaken by a blizzard of one-off fees that technically aren’t taxes and therefore can be imposed by a simple majority vote. Some of these fees are on newly built housing tracts, which means that new buyers might pay property tax rates as high as 2 percent while old-timers like me only pay 1 percent. The other fees are a confusing and inefficient patchwork of tiny surcharges on every undertaking imaginable, while still others fall on groups—like university students—who are least able to afford them. And whatever  else you can say about property taxes, they tend to be fairly stable. California’s overreliance on income and capital gains taxes in the aftermath of Prop. 13 has made its finances a roller coaster over the past 20 years.

else you can say about property taxes, they tend to be fairly stable. California’s overreliance on income and capital gains taxes in the aftermath of Prop. 13 has made its finances a roller coaster over the past 20 years.

And there’s one other little-appreciated bit of fallout from Prop. 13: It’s given Sacramento far more power over local governments. Before Prop. 13, state and local governments all set their own property tax rates. Cities and counties could vote on their own taxes, and those votes would succeed or fail depending on what the money was being used for. After Prop. 13, tax rates were set permanently at 1 percent, but the law was silent on how that 1 percent got divvied up. That power was given to the state, which means that Sacramento gets to decide how much money it gets for itself and how much it allocates to local governments. You can probably guess how this works out.

The tax revolt has had a long run since Prop. 13 was passed, and it’s hardly over yet. But last year, for the first time since 1978, Californians voted to raise their own taxes after a decade of self-inflicted budget crises. Then, at the end of the year, Congress (under duress) agreed to raise taxes on the wealthy for the first time since 1993. In both cases, this was at least partly due to the kinds of problems that Prop. 13 made manifest: a growing realization that the tax revolt has benefited the rich far more than the rest of us and a grudging understanding that at some point you have to pay for the services you want. Californians want decent schools and Americans want to preserve their roads, their military, and their safety net.

Thirty-five years is a pretty fair stretch. But nothing lasts forever, and as it enters middle age the tax revolt is huffing and puffing to stay relevant. Despite what the tea party thinks, tax cuts simply aren’t a serious option any longer, and tax increases are no longer taboo. It’s not 1978 anymore.