I’ve been spending a bit of time this weekend trying to understand better what the real issues are with the Oregon Medicaid study that was released on Thursday and shortly afterward exploded across the blogosphere. Unfortunately, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s next to impossible to explain it in a way that would be understandable to  most people. My readers, however, are not “most people,” so I figure I’ll take a crack at it anyway. The damage may have already been done from the many misinterpretations of the Oregon study that have been published over the past few days, but who knows? Maybe this will help anyway.

most people. My readers, however, are not “most people,” so I figure I’ll take a crack at it anyway. The damage may have already been done from the many misinterpretations of the Oregon study that have been published over the past few days, but who knows? Maybe this will help anyway.

First, to refresh your memory: In 2008, Oregon expanded Medicaid coverage but didn’t have enough money to cover everyone. So they ran a lottery. If you lost, you got nothing. If you won, you were offered the chance to sign up for Medicaid. This provided a unique opportunity to study the effect of Medicaid coverage, because Oregon provided two groups of people who were essentially identical except for the fact that one group (the control group) didn’t have access to Medicaid, while the other group (the treatment group) did.

There are several things to say about the Oregon study, but I think the most important one is this: not that the study didn’t find statistically significant improvements in various measures of health, but that the study couldn’t have found statistically significant improvements. It was impossible from the beginning.

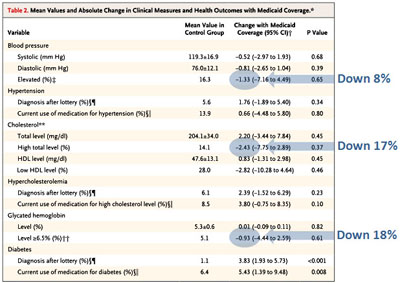

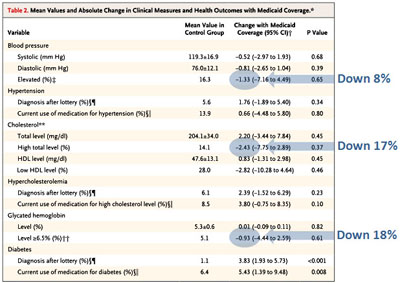

Here’s why. The first thing the researchers should have done, before the study was even conducted, was estimate what a clinically significant result would be. For example, based on past experience, they might have decided that if access to Medicaid produced a 20 percent reduction in the share of the population with elevated levels of glycated hemoglobin (a common marker for diabetes), that would be a pretty successful intervention.

Then the researchers would move on to step two: suppose they found the clinically significant reduction they were hoping for? Is their study designed in such a way that a clinically significant result would also be statistically significant? Obviously it should be.

Let’s do the math. In the Oregon study, 5.1 percent of the people in the control group had elevated GH levels. Now let’s take a look at the treatment group. It started out with about 6,000 people who were offered Medicaid. Of that, 1,500 actually signed up. If you figure that 5.1 percent of them started out with elevated GH levels, that’s about 80 people. A 20 percent reduction would be 16 people.

So here’s the question: if the researchers ended up finding the result they hoped for (i.e., a reduction of 16 people with elevated GH levels), is there any chance that this result would be statistically significant? I can’t say for sure without access to more data, but the answer is almost certainly no. It’s just too small a number. Ditto for the other markers they  looked at. In other words, even if they got the results they were hoping for, they were almost foreordained not to be statistically significant. And if they’re not statistically significant, that means the headline result is “no effect.”

looked at. In other words, even if they got the results they were hoping for, they were almost foreordained not to be statistically significant. And if they’re not statistically significant, that means the headline result is “no effect.”

The problem is that, for all practical purposes, the game was rigged ahead of time to produce this result. That’s not the fault of the researchers. They were working with the Oregon Medicaid lottery, and they couldn’t change the size of the sample group. What they had was 1,500 people, of whom about 5.1 percent started with elevated GH levels. There was no way to change that.

Given that, they probably shouldn’t even have reported results. They should have simply reported that their test design was too underpowered to demonstrate statistically significant results under any plausible conditions. But they didn’t do that. Instead, they reported their point estimates with some really big confidence intervals and left it at that, opening up a Pandora’s Box of bad interpretations in the press.

Knowing all this, what’s a fair thing to say about the results of this study?

- One fair thing would be to simply say that it’s inconclusive, full stop. It tells us nothing about the effect of Medicaid access on diabetes, cholesterol levels, or blood pressure maintenance. I’m fine with that interpretation.

- Another fair thing would be to say that the results were positive, but the study was simply too small to tell us if the results are real.

- Or there’s a third fair thing you could say: From a Bayesian perspective, the Oregon results should slightly increase our belief that access to Medicaid produces positive results for diabetes, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure maintenance. It shouldn’t increase our belief much, but if you toss the positive point estimates into the stew of everything we already know, they add slightly to our prior belief that Medicaid is effective.

- But you can’t say that the results are disappointing, at least not without a lot of caveats. At a minimum, the bare fact that the results aren’t statistically significant certainly can’t be described as a disappointment. That was baked into the cake from the beginning. This study was never likely to find significant results in the first place.

So that’s that. You can’t honestly say that the study shows that Medicaid “seemed to have little or no impact on common medical conditions like hypertension and diabetes.” That just isn’t what it showed.

POSTSCRIPT: That said, there are a few other things worth saying about this study too. For example, the researchers apparently didn’t have estimates of clinical significance in mind before they conducted the study. That’s odd, and it would be nice if they confirmed whether or not this is true. Also: the subjects of the study were an unusually healthy group, with pretty low levels of the chronic problems that were being measured. That makes substantial improvements even less likely than usual. And finally: on the metrics that had bigger sample sizes and could provide more reliable results (depression, financial security, self-reported health, etc.), the results of the study were uniformly positive and statistically significant.

Every time a health insurance company announces a rate hike, a phalanx of conservatives are ready to step in and declare that it’s the fault of Obamacare. But flashy rate hikes aside, overall health inflation has actually been slowing down lately. Jonathan Bernstein wants to know why liberal hackdom has been

Every time a health insurance company announces a rate hike, a phalanx of conservatives are ready to step in and declare that it’s the fault of Obamacare. But flashy rate hikes aside, overall health inflation has actually been slowing down lately. Jonathan Bernstein wants to know why liberal hackdom has been  for 2020, based on the state’s baseline share of coal and gas generation.

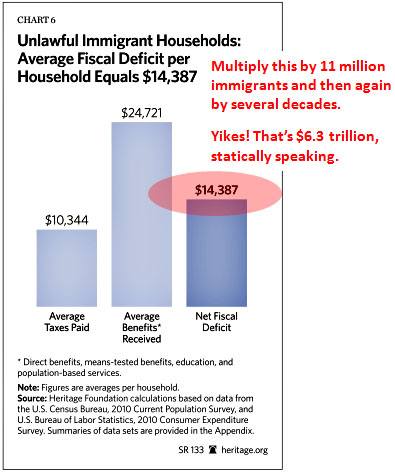

for 2020, based on the state’s baseline share of coal and gas generation. old static scoring. Instead you have to take account of the fact that the tax cut will supercharge the economy, which in turn will produce higher incomes and higher tax receipts even though tax rates are lower. The Heritage immigration report, however, doesn’t take into account the fact that undocumented immigrants are all dynamically creating extra wealth and increasing the size of the economy.

old static scoring. Instead you have to take account of the fact that the tax cut will supercharge the economy, which in turn will produce higher incomes and higher tax receipts even though tax rates are lower. The Heritage immigration report, however, doesn’t take into account the fact that undocumented immigrants are all dynamically creating extra wealth and increasing the size of the economy.  producing a random set of non-battleground voters who are exposed to large numbers of ads.

producing a random set of non-battleground voters who are exposed to large numbers of ads. civilians in the use of standard military firearms so “they’re ready to fight tyranny” yet again. Fellow Southerner Ed Kilgore is

civilians in the use of standard military firearms so “they’re ready to fight tyranny” yet again. Fellow Southerner Ed Kilgore is  most people. My readers, however, are not “most people,” so I figure I’ll take a crack at it anyway. The damage may have already been done from the many misinterpretations of the Oregon study that have been published over the past few days, but who knows? Maybe this will help anyway.

most people. My readers, however, are not “most people,” so I figure I’ll take a crack at it anyway. The damage may have already been done from the many misinterpretations of the Oregon study that have been published over the past few days, but who knows? Maybe this will help anyway. looked at. In other words, even if they got the results they were hoping for, they were almost foreordained not to be statistically significant. And if they’re not statistically significant, that means the headline result is “no effect.”

looked at. In other words, even if they got the results they were hoping for, they were almost foreordained not to be statistically significant. And if they’re not statistically significant, that means the headline result is “no effect.”