Michael Corleone in The Godfather Part 3:

Just when I thought I was out… they pull me back in.

You know, I don’t really enjoy writing endlessly about Barack Obama’s essential powerlessness when it comes to dealing with an increasingly fanatic Republican Party. It’s just so damn gloomy and special pleadingish. But I keep getting pulled back in. Today, a friend of mine emails with a short summary of Ron Fournier’s appearance on Morning Joe today:

John Heilemann asked Fournier the same question that everyone asks Fournier, which he dodges: well, what would you have the President do? Fournier then said, “let me turn that question back on you” and went off a tangent, but not without dropping in at the end of the segment that Obama can get revenue increases if he just

engages with the Republicans. I yelled at the television and scared my 4 year-old. Did he really say that? Yes, he did.

I just don’t get it. What does it take to convince the Dowds and Milbanks and Fourniers of the world? How can any of them still believe that Republicans will ever agree to real revenue increases? George Washington himself could rise from the grave and the House Republican caucus wouldn’t agree to pass a revenue increase for him. What then? Would Dowd and Milbank and Fournier sigh theatrically and mourn the fact that Washington just isn’t the leader he used to be?

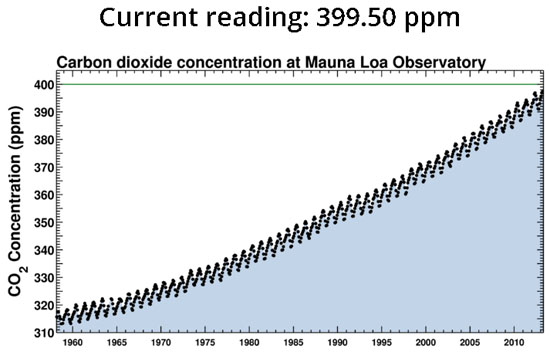

Republicans aren’t going to let Obama raise revenues. They aren’t going to let Obama pass a gun bill—even a watered-down one. They aren’t going to let Obama close Guantánamo. They aren’t going to let Obama fill the vacancies on the DC Circuit Court. They aren’t going to help Obama implement Obamacare. They aren’t going to let Obama address climate change. Period.

They’ve made this crystal clear to anyone who asks. They are true believers and there’s nothing Obama, or Fournier, or anyone else can offer them that would break through their glinty-eyed zealotry. There are no deals to be made, no leverage that can be used, and no schmoozing that will change their minds. This isn’t an Obama problem, it’s a Republican Party problem. Why is such a simple and unambiguous fact so hard to acknowledge?

But just to keep things on an even keel around here, go read Jon Chait’s “What Obama Can Actually Do About Congress.” I endorse all of it. So you see, I agree that there are things Obama could do better, just as there are issues (like Guantánamo detainees) where Obama himself bears some of the blame for our current gridlock.

Now, none of Chait’s suggestions would actually make more than a hair’s breadth of difference. But Obama should do them anyway. After all, you never know, do you?

around 10-20 percent. Since the government was not guaranteeing these mortgages, the banks must have felt the guarantee was unnecessary to get them to issue 30-year fixed rate mortgages.

around 10-20 percent. Since the government was not guaranteeing these mortgages, the banks must have felt the guarantee was unnecessary to get them to issue 30-year fixed rate mortgages.