Last night I read a Politico article about Congress trying to exempt itself from Obamacare. I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. Obamacare doesn’t even apply to big employers, so what’s to exempt?

Well, it turns out that Congress wrote a special provision into the law that ended its own participation in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program and instead requires anyone working on Capitol Hill to buy health insurance through an Obamacare exchange. So that explains that. But it still wasn’t clear what the problem was. As the law stands, they have to choose a health plan through the exchange. So what?

This morning, Ezra Klein explains. The whole thing started back in 2009 when Republicans decided to embarrass Democrats by proposing an amendment that forced members of Congress to use Obamacare. Democrats then surprised them by agreeing to it. The problem, it turns out, is that because the amendment was originally intended to be only for  show, it was poorly drafted. Big employers aren’t even allowed to use the Obamacare exchanges until 2017, so there are no rules for how to handle their premium contributions:

show, it was poorly drafted. Big employers aren’t even allowed to use the Obamacare exchanges until 2017, so there are no rules for how to handle their premium contributions:

That’s where the problem comes in….It’s not clear that the federal government has the authority to pay for congressional staffers on the exchanges, the way it pays for them now in the federal benefits program. That could lead to a lot of staffers quitting Congress because they can’t afford to shoulder 100 percent of their premiums.

….You’ll notice a lot of hedged language here: “Ifs” and “coulds”. The reason is that the Office of Personnel Management — which is the agency that actually manages the federal government’s benefits — hasn’t ruled on their interpretation of the law. So no one is even sure if this will be an issue. As the Politico article notes, some offices, like that of Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), interpret the language of the law such that there’s no problem at all. Others are worried it could be an issue, and are trying to prepare ways around it. The staffs I talked to stressed this worrying was preliminary, and felt the Politico article was jumping the gun. “This whole Politico story is based on a ruling that hasn’t even come down yet,” one griped.

So there you have it. But why am I spending time this morning providing you with an explanation for a problem you probably didn’t even know existed? Because it allows me to make a point, of course.

But which point? Jon Chait, for example, pairs this up with another story and suggests that Politico is a little too dedicated to covering politics as theater and should try a wee bit harder to understand the actual policy it writes about. Fair enough!

But the point I want to make isn’t about Politico, it’s about Obamacare itself, and my biggest fear for its future. My biggest fear is not about the various implementation problems that Obamacare is going through right now. Conservatives are making plenty of hay over these obstacles right now, but the truth is that any big law will go through growing pains. When you dig into them, it turns out that most of the problems conservatives are crowing about are either (a) bogus or (b) not really very serious. A single small union complaining about the law, for example, is just not that big a deal, no matter how much Rush Limbaugh tries to pretend otherwise. Ditto for Max Baucus’s concerns about marketing; conflicts with university health plans; a supposed increase in workers being forced into part-time work, and so forth.

No, my biggest concern is what happens after 2014. No big law is ever perfect. But what normally happens is that it gets tweaked over time. Sometimes this is done via agency rules, other times via minor amendments in Congress. It’s routine. But Obamacare has become such a political bomb that it’s not clear that Congress will be willing to fix the minor problems that crop up over time. There’s simply too big a contingent of Republicans who are eager to see Obamacare fail and are actively delighted whenever a problem crops up. This has the potential to be a problem that no other big law has ever had to face.

We’ll see how this works out. Maybe after 2014 things will cool down a bit and normal horse trading will start up again. But I’m not so sure anymore. After all, I figured that might happen after the November election, and when John Boehner acknowledged that “Obamacare is the law of the land,” it seemed like a good sign even with all the hedging he put around it.

But nothing has changed. Republicans are still fervently determined to destroy Obamacare any way they can, and this means that tweaks and fixes are unlikely. Instead, they’re going to dig in their heels and gleefully watch as people suffer because of minor implementation glitches that could be easily avoided. In the end, I suspect this strategy won’t work. But you never know. It might.

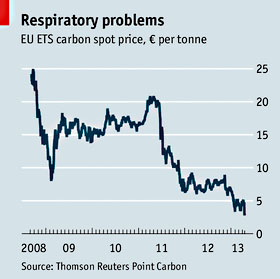

carbon permits. As a result, the price of carbon permits has dropped off a cliff, and they’re now so cheap that they’re having virtually no effect. So does this mean the whole program is a failure?

carbon permits. As a result, the price of carbon permits has dropped off a cliff, and they’re now so cheap that they’re having virtually no effect. So does this mean the whole program is a failure?  Agriculture Department loans in the 80s and 90s. The original compensation program, usually called Pigford after the class-action lawsuit that got it going, eventually led to a second settlement, Pigford II,

Agriculture Department loans in the 80s and 90s. The original compensation program, usually called Pigford after the class-action lawsuit that got it going, eventually led to a second settlement, Pigford II,

discussion and the advisor would struggle to catch up.

discussion and the advisor would struggle to catch up. show, it was poorly drafted. Big employers aren’t even allowed to use the Obamacare exchanges until 2017, so there are no rules for

show, it was poorly drafted. Big employers aren’t even allowed to use the Obamacare exchanges until 2017, so there are no rules for