A few years ago California adopted what’s mockingly called a “jungle primary.” Instead of Democrats and Republicans each running their own primary, there’s just one big primary and the top two vote-getters move on. That might be two Democrats, two Republicans, or one of each.

The idea behind the top-two primary was simple: it would produce more moderate candidates. Instead of appealing to the most extreme segments of the electorate, candidates would jostle to get votes from the center. Democrats could benefit from appealing to right-leaning centrists and vice versa for Republicans.

So did it work? So far, the answer appears to be no, though the evidence is a little hazy because of another change California made at around the same time: moving all initiatives to general elections. Because of this, turnout at primaries plummeted. Unsurprisingly, it turned out that Californians were eager to go to the polls to vote for initiatives, but not so eager when there was nothing more interesting at stake than a primary battle for the state legislature. This changed the composition of the primary electorate, so it’s hard to make solid comparisons with previous years.

That said, it still doesn’t look like much changed. In 2012, for example, researchers polled voters using both a traditional ballot and a top-two ballot. There was no difference in the results. One reason is that most voters knew virtually nothing  about any of the candidates. Were they moderate? Liberal? Wild-eyed lefties? Meh. Voters weren’t paying enough attention to know. Mark Barabak of the LA Times summarizes a pile of studies published recently in the California Journal of Politics and Policy:

about any of the candidates. Were they moderate? Liberal? Wild-eyed lefties? Meh. Voters weren’t paying enough attention to know. Mark Barabak of the LA Times summarizes a pile of studies published recently in the California Journal of Politics and Policy:

Voters were just as apt to support candidates representing the same partisan poles as they were before the election rules changed — that is, if they even bothered voting….”To summarize, our articles find very limited support for the moderating effects associated with the top-two primary,” Washington University’s Betsy Sinclair wrote, summarizing half a dozen research papers.

For starters, voters will have to pay far closer attention to their choices. Some candidates may have hugged the middle in a bid to entice more pragmatic-minded voters, but the research suggests relatively few voters noticed. There was little discernment between, say, a flaming liberal and a more accommodating Democrat; in most voters’ minds they fell under the same party umbrella.

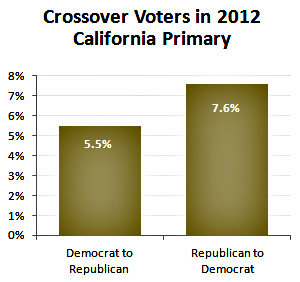

In addition, voters will have to be less partisan themselves, showing a far greater willingness to support a moderate of the other party over a more extreme member of their own. Research into 2012’s state Assembly races found an exceedingly small percentage of so-called cross-over voters: just 5.5% of Democrats and 7.6% of Republicans sided with a candidate from the other party.

Now, it does turn out that moderate Republicans were more willing to cross over than any other group: 16.4 percent of them crossed over to vote for Democrats. However, this is most likely due to the simple fact that California has a lot more Democratic districts than Republican ones. This means there are a lot more districts where voting for a Republican is useless—and always has been.

The full set of studies is here. Bottom line: early evidence doesn’t suggest that a top-two primary makes much difference. Perhaps it will in the future as voters get more accustomed to it, but for now they’re voting the same way they always have, and for the same kinds of candidates.