The New York Times ran a piece this weekend about the growing burden of paying public pensions. Naturally it features a few examples of outrageously high pensions, but the overall gist is that the cost of pensions is getting so high that it’s crowding out spending on other things. Dean Baker comments:

Workers sign contracts that specify compensation. Most of it is in direct pay, but benefits like pensions are often part of the contract….Taking back pensions for which people worked is like taking back a portion of their pay after the fact.

….As far as the claim that public employees are overpaid, most research shows that they are actually paid less than their private sector counterparts, when controlling for education and experience….While the piece implies that public employees typically get generous pensions, this is not true. The Detroit pension system, which is referenced in the piece, pays an average annual benefit of $20,000 a year, or less than $1,700 a month. Most other public pension systems provide comparable benefits to typical employees as opposed to highly paid doctors and football coaches.

For the most part, public pensions are fairly ordinary. The biggest exception is police and firefighters,¹ who are often allowed to retire after only 20 years; are allowed to spike their pensions; are able to take part in special semi-retirement programs that boost their pensions even more; frequently take disability pensions; and just generally have pensions that pay them a high percentage of their working salaries.

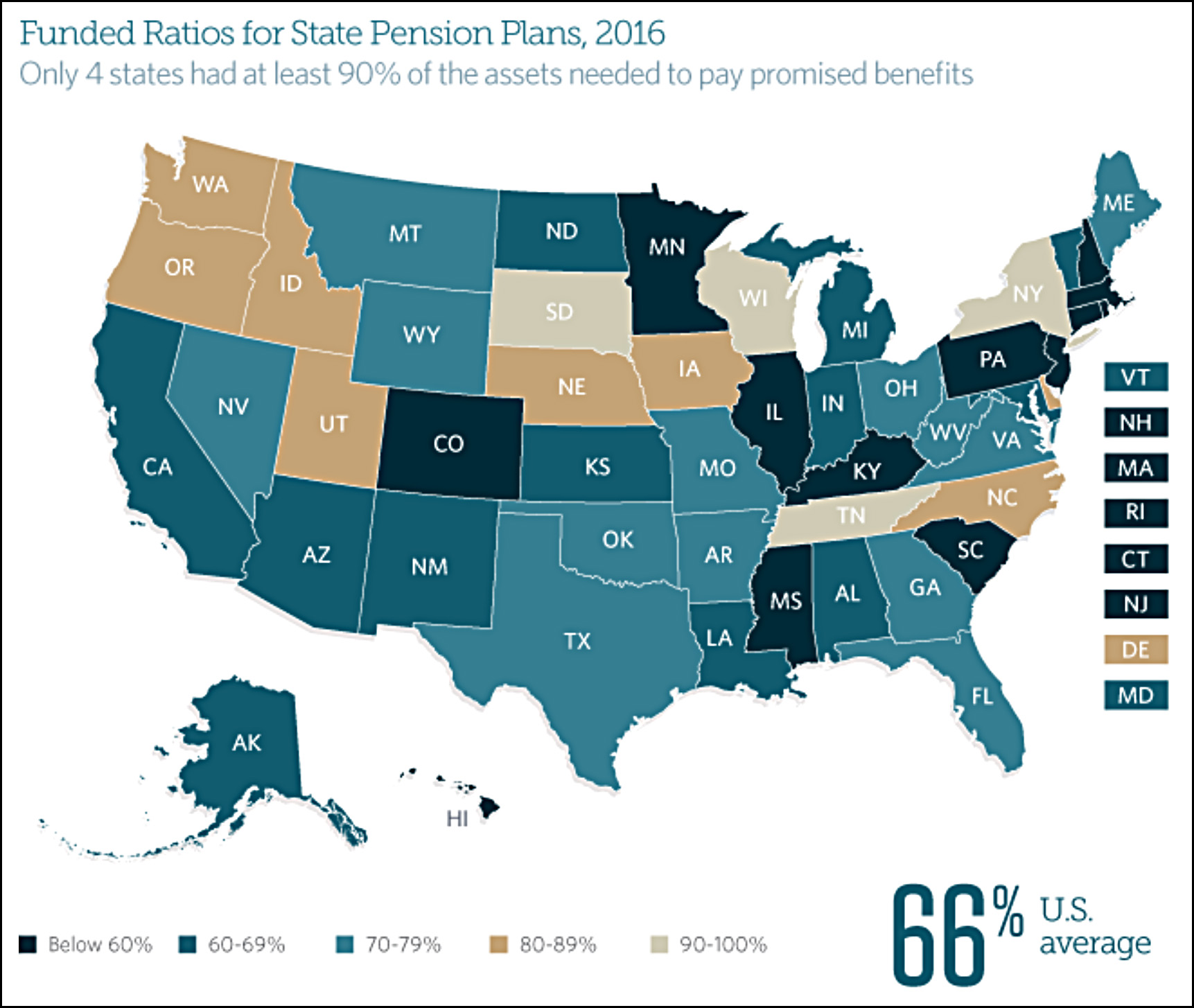

But put that aside. If they can negotiate all that stuff, then bully for them. The real issue, as everyone knows, isn’t so much the size of public pensions as the fact that they’re almost never fully funded. Politicians, who mostly work on timeframes no further out than the next election, are simply more willing to negotiate generous pensions than they are to negotiate higher salaries that might require tax hikes on their watch. It’s like Wall Street’s IBGYBG: “I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone.” And sure enough, now that the pension bills are coming due, all the politicians who passed the buck—literally—are safely out of office.²

The real answer all along has been simple: negotiate any pension you want, but you have to fully fund it with no wild-ass investment return assumptions. Done properly, an extra $1,000 in pension income would cost about the same as a $1,000 salary increase, so politicians would have no special incentive to prefer one over the other.

It’s a little late for that, of course, and although lots of cities and states would love to take back a chunk of worker pensions, they can’t do it. It’s all specified in a contract, after all, and courts will enforce those contracts. One way or the other, paying out old pensions is probably going to require an average increase in state and local taxes of about 5-10 percent or so. Maybe more, depending on where you live. The sooner everyone owns up to this, the better off we’ll all be.

¹Although in Los Angeles the hot ticket is to work for the Metropolitan Water District. Hoo boy. Nobody shoots at them and they don’t have to fight fires. But they get paid a fortune and their pensions are sky high.

²And collecting a pension, of course.