What happened to manufacturing in the aughts? The usual story is that employment plummeted but output increased. Apparently manufacturing got a lot more efficient during this period, which is why so many people lost their jobs.

Susan Houseman begs to differ. Using sophisticated decompositions, she finds that it’s all a mirage: computer manufacturing got more efficient, but that’s about it. And even that’s a bit of a mirage due to the way inflation is calculated: it’s not that American workers are making a lot more computers than they used to, it’s that they’re making more MIPS, so to speak. It’s the same number of boxes, but a whole lot more computing power.

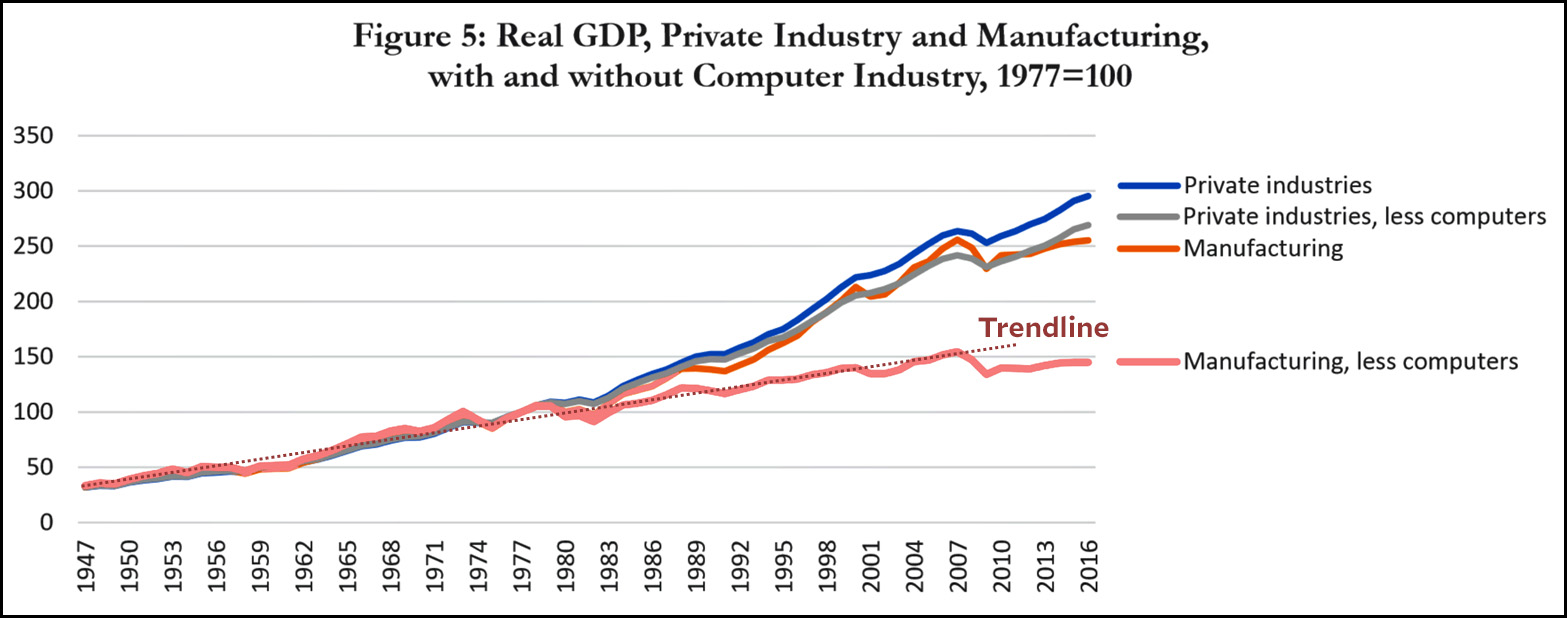

The conclusion she draws from all this is that the loss of manufacturing jobs after 2000 was more likely related to China than to automation. But I’m a little confused. Let’s start with Houseman’s own chart:

When you pull out computers, manufacturing output grows at a pretty sluggish rate compared to the rest of the economy. The thing is, it looks like this growth rate has been pretty constant ever since 1947 right up to the Great Recession. It doesn’t tell us much.

But it’s easy to zoom in. The mega-growth of the computer sector is no secret, and you hardly need access to sophisticated data to see it. In fact, it’s so well-known and so obviously important that the Fed helpfully produces a standard series for all manufacturing production excluding computers. Let’s look at that:

After the 2000 recession, manufacturing growth picks up, but it’s slower than before. The growth rate in the aughts is about a third lower than in the 90s. Now here’s manufacturing productivity growth:

After the 2000 recession, manufacturing productivity grew faster than before. The productivity growth rate in the aughts is about 75 percent higher than in the 90s. So we have two data points related to the manufacturing sector excluding computers:

- The growth rate of manufacturing output slowed down after 2000.

- The growth rate of manufacturing productivity speeded up.

The first bullet suggests job losses due to China: we’re making less stuff than we should because we’ve offshored a lot of it. The second bullet suggests job losses due to automation gains: we’re losing jobs because output per worker is going up faster than before. I don’t really have a dog in this fight, but it sure looks to me like both played a role. Based on the slope of the trendlines I’d guess that it’s about 60 percent automation and 40 percent China. But I’m wide open to better estimates—of which there are many, I’m afraid.