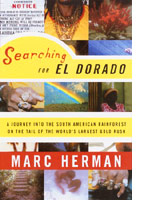

In the sixteenth century, not long after Spanish explorers found their way to the world they termed new, a myth developed about a king who bathed himself in gold, a myth that soon evolved to include a city built from the precious metal. The Spanish called both El Dorado, and devoted costly expeditions and frittered away years hacking through the jungle, searching for the golden ones.

Nobody ever managed to locate, let alone capture, El Dorado the man, and nobody set foot in the utopian city. (Though if you take proto-travel writers like Sir Walter Raleigh at their word, some did come tantalizingly close.) Despite, or perhaps because of, this epic tale of frustrated ambitions and loss of life, the myth has persisted through the centuries, and journalist Marc Herman has found ample evidence that what was unreal but nonetheless believable almost 500 years ago remains as unreal and believable today.

Beginning in 1994, Herman traveled to Guyana, a country rich in timber, diamonds, and, gold, but poor by almost every other measure, including per capita income, gross domestic product, and life expectancy. Yesterday’s conquistadors have become young, local miners, working in small groups inside holes they dig with hand tools, as well as huge international mining concerns. Herman balances his on-the ground reporting with historical background about gold rushes, mining technology, and the economics of gold, and talks to everyone — miners and mining company executives alike. In the book’s strongest chapter, he travels into the interior with two men who quit mining to drive a supply truck, a steadier if less often romanticized occupation.

If Herman is at times too hesitant to draw conclusions, he nonetheless remains sensitive to the complexity of the story. He acknowledges that mining companies, however gargantuan their operations and however much cyanide they use in the mining process, are kinder to the environment than the local miners, who poison the water and themselves with mercury.

Although contemporary miners have discovered more gold than the Spanish ever did, they are not getting all that rich. Gold is not as valuable as it was, and its price continues, save the occasional spike, to drop. For the mining companies, hunting for gold is grossly inefficient — the country’s largest mine in typical years dug up twenty million tons of rock to produce 300,000 ounces of gold. For the local miners, the scale is smaller but results similar: they do not get rich quick so much as make ends meet laboriously. And yet Guyana cannot stop mining; the livelihood of its people, its economy, everything depends on the unending search for more gold.